On the first day of school at Orr Middle School in eastern Las Vegas, teacher Annie Bhatnager was teaching her new immigrant students how to ask each other basic questions in English.

“Let’s practice it one more time, ready?” Bhatnager said to the class, which is known as the “Newcomer” class.

“Where are you from?” the class of sixth, seventh and eighth-graders chorused in accented English. “I am from….”

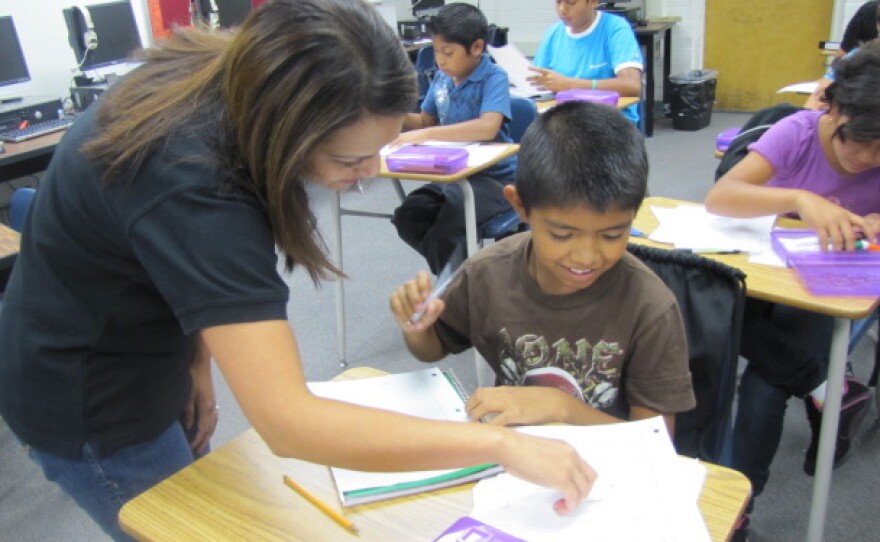

Bhatnager paused by the desk of a student in the front row.

“So let’s start with you, Safari,” Bhatnager said. “Where are you from?”

“I am from Africa,” Safari answered, concentrating on each word.

They went around the room and the 23 students each responded: China. Nepal. Eritrea. Guatemala. The list went on.

Orr Middle School has one of the highest populations of refugee and immigrant students in the school district. These students pose a distinct challenge to public schools. Many come from poor or war torn countries where they didn’t get much education, and they’re at high risk of dropping out.

And it’s Bhatnager’s task to teach them all English.

In Nevada, 30 percent of children don’t speak English as their first language, which is the highest density in the country—according to an analysis by the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington-based think tank.

In most schools in the Clark County School District, ELL students are placed into math, history and science alongside their English-speaking peers. Teachers are trained to teach both native speakers and English Language Learners at the same time.

But Orr Middle School has opted for a different strategy. The school created a Newcomer Program—a separate, year long class for students who are brand new to the country to help them in the transition.

It means that Bhatnager can start with the basics, which is what this class demands.

The first week of school she showed the class flashcards with the letters of the alphabet. In unison, the students called out the names of the letters. It went smoothly until the letter E.

“Oh wait, I heard some people say ‘A’,” said Bhatnager. “I know in Spanish this is ‘A’ – but in English it’s ‘E’.”

In the Newcomer program, students spend three class blocks every morning learning English with Bhatnager. In the afternoon, they have a separate math class, as well as physical education and chorus, which they take with their English-speaking peers.

The students will stick to this schedule for at least their first year. By their second year, they will enroll in mainstream classes, though the school will closely monitor them.

“The first step has to be becoming comfortable,” said Olga Shaner, who serves as the school’s guidance counselor for immigrant students and liaison to their parents.

“They’ve needed that introduction into the culture of the United States to become comfortable and then to be able to work on the English acquisition,” Shaner said.

The counselor said it is a race to get the kids as caught up as much as possible before they go to high school, where they will find less of a safety net.

“If they get to us in sixth grade, we have three years,” Shaner said from her office, in a brief break between meetings with parents. “Three years to give them as much English, as much practice as they can, so that when they hit high school they have a good chance.”

This year, facing a $150 million dollar budget shortfall, the Clark County School District scaled back ELL programs. Special facilitators who help ELL students in the classroom were virtually eliminated when their ranks were cut from 160 to 10.

At Orr, the Newcomer program is also dealing with fewer resources, but it has managed to stay afloat. One reason is a grant from the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement.

About 50 of the school’s 918 students are refugees. About half of the school is considered to be learning English. That’s because this neighborhood, with its affordable apartments and access to public transportation, is attractive to newly arriving families.

Since the 1990’s, a growing number of schools around the country have begun to experiment with Newcomer programs that orient brand new children in their own classroom for a fixed period of time. Some have been quite effective.

Still, education experts are debating the best way to implement these kinds of programs. For instance, there is a longstanding dilemma about when students should transition from a Newcomer program into their grade-appropriate curriculum.

“If I spend a year in a newcomer program and I'm not getting seventh-grade math, science, social studies, history, whatever, when am I going to get that?” said Patricia Gandara, a professor of education at UCLA.

And it is not just academic content that can be lost in a Newcomer class. In a separate classroom, new immigrants give up critical contact with English-speaking peers.

“One of the important ways that children learn the languages is by being mixed with other children who speak that language, and therefore being placed into social situations where the language is experienced naturally,” Gandara said.

The Southwest has the highest density of English Language Learners in the country. And questions over how to ease these kids into mainstream classrooms and whether to use Spanish to transition Spanish-speaking immigrants, have sparked political fights in states like Arizona and California. There's still little consensus on what methods really work.

Back at Orr, teachers and counselors stress that these middle school years are key to the success of these new kids.

Amanda Sandinos, a cheerful 6th grader with round cheeks and wavy brown hair, is happy to be in the Newcomer class.

She didn't like being placed in a regular classroom at her previous school when she arrived from Cuba last March.

“I felt sad because I ate lunch alone, “ she said in Spanish.

Amanda said even the other kids who spoke Spanish wouldn’t talk to her. Now, at Orr, she jokes and gossips with her new friends.

“It’s good to be here, because I can have opportunities that weren’t possible back there,” Amanda said, referring to Cuba.

One day she hopes to attend an American university. And what happens in her classroom this year, could determine whether she gets the language skills she needs to catch up to her peers and make it there.