In September 2021, viral photos of a brand new Amazon warehouse towering over a Tijuana shanty town kicked off a conversation about the role multinational corporations play in exacerbating global inequality.

Tijuana’s business community praised the new addition as a welcome boost to the local economy. The city issued a press release stating the new warehouse in the neighborhood known as Nueva Esperanza would contribute “to the ongoing (post-pandemic) economic recovery in various productive sectors.”

Amazon Mexico told local newspapers that the company feels, “great responsibility towards the communities where we operate, and we are pleased to be able to offer hundreds of job opportunities in Tijuana.”

Amazon was never specific about what it meant by “great responsibility.” Yet, people in the community hoped the company would do more for them than just fill the warehouse with workers.

In the three years since Amazon arrived, its most tangible contributions to Nueva Esperanza, other than low-wage jobs, have been donated school supplies and reading workshops for local children.

While residents appreciate the support, it is minuscule compared to the approximately $3.5 billion in revenue generated by Amazon Mexico.

The neighborhood continues to lack paved roads or a functioning sewage system, and repurposed plywood is the primary home building material — basic services that residents have been asking the Tijuana city government to provide for decades.

“There is still no water or drainage system,” said Marly Trinidad Mejia, a mother of three who, like most of Nueva Esperanza’s residents, moved there in recent decades hoping for a better life.

“For those of us who come from other parts of the country, this place gave us a new start,” Mejia said in Spanish.

It is one of Tijuana’s many so-called “informal” neighborhoods — created by squatters who built makeshift homes on vacant land and eventually transformed it into a community with stores, small businesses and even a public school.

Mejia earns $2,000 pesos a week working as a janitor for a medical device manufacturer in the adjacent industrial park that’s also home to Amazon’s warehouse. That comes out to about $100 U.S. dollars a week, which is below minimum wage in the U.S. but twice as much as what she used to make in Chiapas, a state in southern Mexico.

Mejia believes their corporate neighbors should reinvest more of their profits into Nueva Esperanza.

“They have so much money, and we don’t see any of that supporting our neighborhood,” she said.

‘Radical inequality’

The juxtaposition of one of the richest companies in the world setting up shop amid such poverty is also striking to Teddy Cruz, the director of Urban Research at UC San Diego’s Center on Global Justice.

“The photo of the Amazon warehouse next to this very precarious informal settlement was very dramatic and really illustrated a lot of what our research is really addressing, which is radical inequality,” he said.

Amazon was hardly the first U.S corporate behemoth to establish operations in Mexico. There’s been a decades-long stampede since 1994, when Congress ratified the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA.

NAFTA, which was replaced by the similar U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement in 2020, eliminated tariffs on most goods imported between the U.S., Mexico and Canada. The combination of Mexico’s low wages and its proximity to the world’s biggest consumer market made Tijuana an ideal location for the post-NAFTA world.

Today, there are close to 600 warehouse and/or light industrial operations, known as maquiladoras, in Tijuana that generate approximately $40 billion each year, according to Cruz.

But, as these businesses prosper, Cruz asks: “Can some of the revenue that comes out of these profits enable a more equitable distribution (of resources).”

Many say based on the actions of corporations, the answer is an emphatic no. However, Cruz and other corporate watchdogs do acknowledge a few bright spots.

Among them is Nueva Esperanza’s community school. It opened five years ago with just 10 students learning under a canopy. Today, it has more than 200 students, several classrooms and brand-new bathrooms.

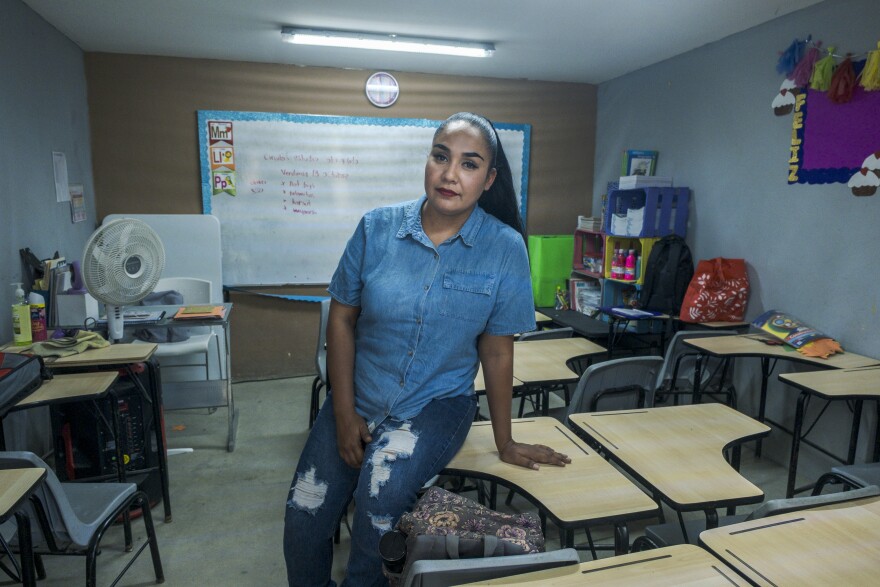

“Little by little, the entire community came together,” said Maria Patricia Chavez, the school’s director.

The first classroom was a makeshift structure held together by random pieces of plywood, mismatched two-by-fours and even a donated garage door repurposed as a wall.

The new structures were funded through a collaboration among the Baja California state government and local nonprofits. Students are particularly excited about the bathrooms, Chavez said.

“Some of them may not have toilets in their home,” she said.

Chavez added that the school’s corporate neighbors, including Amazon, have been supportive. Amazon donated 230 books and 300 literacy kits for the school library. Amazon also sends volunteers to run literacy workshops for students.

“We understand the importance of supporting the communities in which our employees live and work,” Austin Stowe, Amazon spokesperson said in a statement to KPBS. “It’s why we’ve partnered with numerous local organizations in Tijuana to support important causes like literacy, health and food insecurity for residents in Nueva Esperanza.”

Amazon Mexico has invested more than one billion pesos (about $50 million U.S.) in Baja California and created 100 direct and 350 indirect jobs since launching operations, Stowe added.

Jabil, a medical device manufacturer, donated two dozen desks and more than 40 chairs. Employees also distributed 160 meal kits for the students and organized a community fair that brought various health services free of charge to the neighborhood.

Most recently, Jabil sponsored the school’s sixth-grade graduation where each graduate received a backpack full of school supplies, a sweatshirt and snacks.

“At Jabil, we strive to make a positive impact on people in the communities in which we live and work,” a spokesperson wrote in a statement.

But there are clear limits to the corporate generosity.

Chavez said Amazon declined requests for spare wood and other materials to repair a broken roof.

“There are requests that they say no to,” she said.

The roof’s wooden beams and plywood eventually collapsed from water damage, prompting the entire school to shut down for several months this fall, she added.

While Chavez doesn’t blame Amazon for the collapse, she said it would’ve been nice of them to help.

More cooperation needed

Cruz described the corporate contributions as helpful, but ultimately, “symbolic and low-scale.” Nueva Esperanza would benefit more from long-term infrastructure improvements, Cruz said.

For example, developers or companies can install solar panels on the roofs of maquiladoras and share the energy they generate with their neighbors through micro-energy grids.

Those efforts, Cruz said, require collaboration from governments, corporations, academics, residents and local nonprofit organizations.

“Obviously we know that this is not just the responsibility of the factories,” he said. “We need to really open up new types of collaborations to really tackle these problems.”

Residents of Nueva Esperanza told KPBS that the bulk of the responsibility falls on Tijuana’s government.

“We are missing a lot of government support here,” said Blanca Vanesa Sosa, who has two daughters in the school.

The lack of government investment is particularly noticeable when it rains, Sosa said. The unpaved roads and lack of storm drain system create a river of mud through the entire neighborhood.

“It’s a total disaster, nobody leaves their house because of the mud,” she said.

Karla Ruiz was Tijuana’s mayor when Amazon opened its warehouse. At the time, she told newspapers, “if you change an environment, it transforms the surrounding area.”

Ruiz is no longer in office. Her successor, Montserrat Caballero declined an interview request before she left office in October.

The city’s current mayor, Ismael Burgueno, could not be reached for comment.