Former President Donald Trump’s “big, beautiful wall” along the southern border is one of the most divisive issues in American life, regularly prompting condemnation from Democratic lawmakers.

But there’s another wall — a virtual wall that the federal government has spent hundreds of millions of dollars to develop — that has widespread bipartisan support.

Democrats who don’t want to be labeled as proponents of “open borders,” have described the virtual wall as a more humane alternative. In 2019, San Diego Rep. Scott Peters, D-50, called for “border security measures we could all agree on.”

“It might be sensors and radar to spot moving people and objects in any weather or any time of day, it might be cameras mounted on drones to surveil places where the terrain is tough to monitor,” Peters said in a video address to constituents. Peters did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

However, privacy advocates say the virtual wall has been shrouded in secrecy and experts on immigration question its effectiveness.

A vast network

The wall consists of more than 350 surveillance towers along the U.S.-Mexico border, and nearly 80 more planned for 2024. Some of these towers can spot someone 7.5 miles away — but until a month ago, their exact location was a mystery.

“Nobody really had a good sense of where these towers were,” said Dave Maass, director of investigations at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a San Francisco-based privacy rights organization.

Maass and his colleagues spent months putting together the most comprehensive map of border surveillance available to the public. Their mission took them to remote corners of the Arizona desert and isolated sections of the Rio Grande river.

They found towers in desolate desert crossings, residential neighborhoods, community college campuses and even near a dog beach in Del Mar.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation’s work paints a different picture than what policymakers normally describe when they talk about the border, Maass said.

“In the imagination of people in D.C. and people in the national media, the border is just this desert wasteland,” he said. “And the only people you would ever encounter out in the border are human traffickers, cartels, or smugglers. Now, folks in San Diego know that’s not true. People live along the border.”

The Fourth Amendment protects people in the United States from unreasonable searches and seizures. However, federal law gives U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) the authority to conduct warrantless searches within 100 miles from “any external boundary of the United States,” which include borders and coastlines.

“Anywhere that’s a border zone, this idea of things within 100 miles of the border, don’t have the same Fourth Amendment projections that other places inland have,” Maass said.

But a spokesperson said in a news release that the towers give CBP “a significant leg up,” against criminal networks, and are “an essential part of border security.”

Along with the leg up come serious privacy concerns, Maass said. He cited recent examples of federal border agents gathering information on activists, lawyers, humanitarian workers, and journalists.

Safety concerns

Other experts said the virtual wall — just like its physical counterpart — causes more migrant deaths along the border. It also fails to address the most common drug smuggling method, which is to simply drive illicit drugs through legal ports of entry, they said.

There is a direct correlation between militarization along the southern border and migrant deaths, according to Sam Chamber’s research.

Sam Chambers is a University of Arizona researcher who focuses on patterns of migrant deaths in relation to border infrastructure. From a migration perspective, the virtual wall has the same impact as the physical wall, he said.

“People moving around, out of sight of these towers, means they are taking longer journeys,” he said.

This puts migrants at risk of kidney damage, dehydration, heat stroke and death, Chambers said.

So far, Chambers’ research has primarily been limited to Arizona. But he says the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s virtual border map will allow him to expand into California and Texas.

“Now that this data exists, I’m looking at researching what’s happening in the rest of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands,” he said.

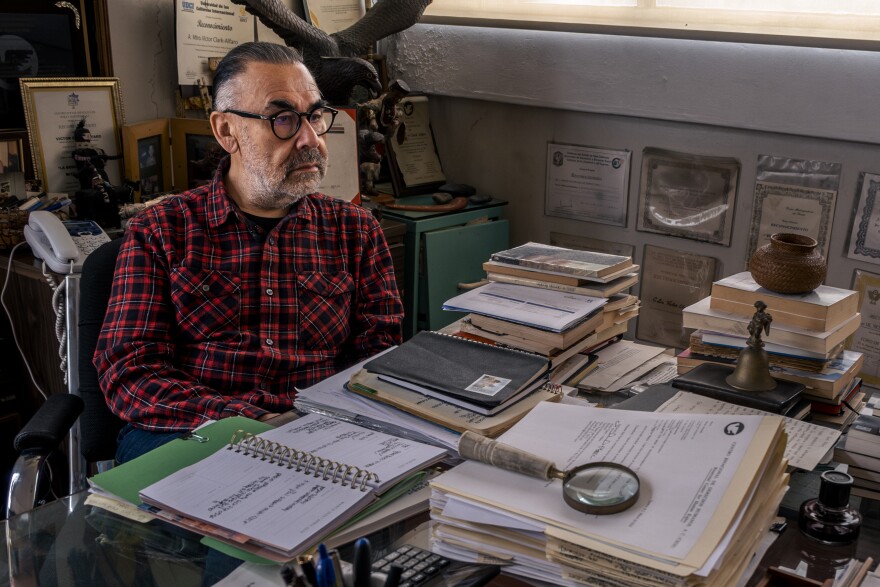

What’s more, human smugglers aren’t deterred by the virtual wall, according to Victor Alfaro-Clark, a social anthropologist who has studied human and drug smuggling since the late 1980s.

Alfaro-Clark teaches a class at San Diego State University where students interview human smugglers in Tijuana. He knows smugglers in Tijuana, who are also known as "coyotes."

“The coyotes tell me that there has not been any impediment,” Clark-Alfaro said. “They continue to cross.”

While the towers make crossing more difficult, it just means the coyotes can charge more money, he added.

When it comes to drugs, the federal government’s own statistics show that the majority enter the U.S. through legal border crossings. Putting up surveillance towers in remote parts of the border isn’t going to stop that, Clark-Alfaro said.

Consider that between 50,000 and 70,000 vehicles cross the San Ysidro Port of Entry every day. And CBP only has the capacity to send a fraction of them to secondary inspection.

“The volume of vehicles is huge and that presents a lot of opportunities,” Clark-Alfaro said.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation hopes increased transparency about the virtual border wall will make the public more informed about the border — or at least know what rights people have and don’t have along the borderlands, Maass said.

More than 200,000 people live within 100 miles of a border, according to the ACLU.

This includes major metropolitan areas like New York City, Los Angeles, San Diego and Chicago. The entire state of Florida lies entirely within the “external boundaries” of the United States.