Republican Congressman Darrell Issa of Vista recently returned from a fact-finding mission to Central America and blamed impoverished economies for the unprecedented number of children entering the U.S. illegally.

Issa said the new arrivals should be expeditiously deported.

But if economics is the main trigger, why aren’t kids also coming from Nicaragua, Central America's poorest country and one that has strong ties to the U.S., dating back to the 1970s?

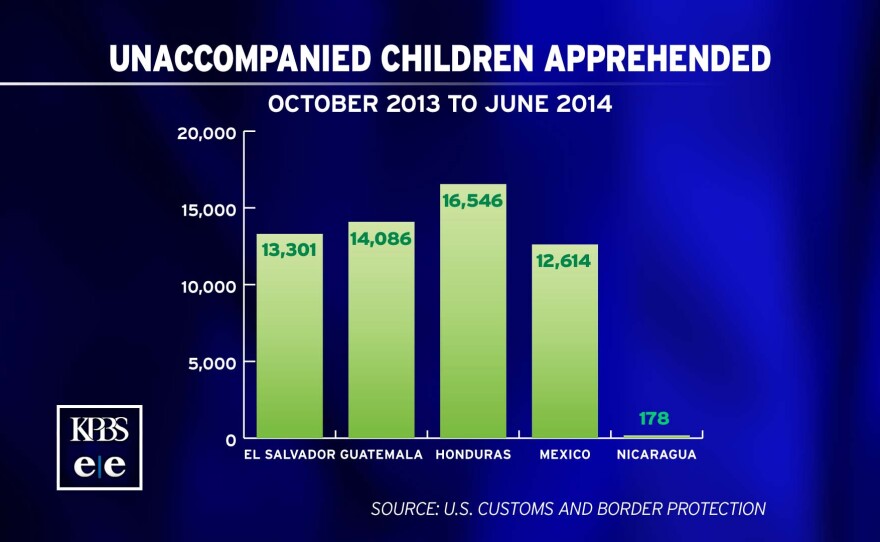

The U.S. Border Patrol apprehended just 178 Nicaraguan children sneaking across the border alone between Oct. 1, 2013, and June 30, 2014, compared to 16,546 children from Honduras, the origin of the greatest number of children apprehended.

Nicaragua has extreme poverty, but it lacks what the White House and experts on the region have also attributed as a cause for the migration: high crime and violence.

The alarming influx of children and families from Central America has fueled demonstrations and debate over U.S. immigration policy and the causes of the emigration. Most of the children are from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras.

Nicaragua is striking in its absence from the pool of child immigrants and from America’s national conversation about them.

It is the second poorest country in Latin America, behind Haiti. It is sandwiched between Honduras on the north and Costa Rica on the south.

It shares a history of revolutionary upheaval in the latter half of the 20th century with its northern Central American neighbors Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. In modern times, it shares an open borders policy and economic regime with those countries.

But unlike its neighbors, Nicaragua has a relatively low crime rate, an absence of transnational gangs and a generally trusted police force that focuses on crime prevention, according to a KPBS examination of historical documents, economic information, and interviews with U.S. and Central American academics, journalists and residents.

“During the '90s, [Nicaragua] really invested in trying to reform the police,” said José Miguel Cruz, a professor at Florida International University and native of El Salvador who has studied Central American gangs for nearly two decades. “That allowed them to control crime in a very effective way.”

Plus, Nicaragua's migration patterns differ from its northern neighbors.

A revolution changed everything

Among the few sounds you'll hear on muggy nights in Managua’s mostly quiet neighborhoods is the periodic whirr of a referee’s whistle. It belongs to a neighborhood night watchman, often seen riding around on an aging mountain bike, tires sagging.

He blows his whistle to let the neighbors, who have pooled money to pay him, know that he’s out there, and everything is calm.

Most night watchmen in the nation's capital carry nothing more than a baton, if even that, to deter the bad guys, a stark contrast to Nicaragua’s neighboring countries, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, where shotguns and automatic weapons are the norm.

The difference is a clear reflection of citizens’ fear of crime. In a 2013 survey, 30 percent of Guatemalans and 28 percent of Hondurans said crime was their country’s most pressing problem, while just 3 percent of Nicaraguans said so.

This fear is borne out in statistics: The homicide rate in Honduras — by far Central America’s most violent country and widely considered the most violent in the world — is eight times that of Nicaragua: 90.4 murders per 100,000 people compared to 11.3 per 100,000.

Guatemala’s murder rate is 39.9 per 100,000 people and El Salvador’s is 41.2 per 100,000 people, according to the U.N.'s Office on Drugs and Crime. (The U.S.’s murder rate is 4.7 per 100,000 people.)

Why doesn’t Nicaragua have the same crime problem? Part of the answer stems from the Sandinista revolution of the late 1970s.

The Sandinistas overthrew Anastasio Somoza — the last in a family dynasty that controlled the country for 43 years — in 1979. At the time, opposition to Somoza was overwhelming, said Jeffrey Gould, a historian who’s studied Nicaragua since the 1980s.

"They had just gotten rid of a repressive dictatorship," Gould said, "so when the Sandinistas took over, they set out to create a different kind of police force, in tune with the local population and their needs, rather than being oppressive.”

Judy Butler, an American journalist who’s lived in Nicaragua for 31 years, said “there was a cleaning out of the military and other structures of government that never happened in ... Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras."

In Guatemala and El Salvador, where revolutionary efforts failed, peace accords between the government and guerrilla forces called for cleaning up and modernizing state security forces but stopped short of scrapping them and starting over.

Cruz, the Florida professor who has studied Central American street gangs, put it this way: “Bad apples continued corrupting new institutions” in those countries.

Nicaragua has good cops

Today, corruption isn’t nearly as prevalent within Nicaraguan security forces as it is in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, Butler and other experts said. And cops are actually liked in Nicaragua.

“I never really witnessed a society in which people got along so well with the police,” Gould said.

In recent years, Nicaragua's national police director, Aminta Granera, has consistently ranked as the most popular public figure in Nicaragua, with an 80 percent approval rating in a recent poll.

In comparison, a 2011 poll found that only 15 percent of Guatemalans have “some” or “a lot” of confidence in their police force.

The Nicaraguan police force focuses on community policing — working with citizens and organizations to solve problems and prevent violence.

"The Sandinista Party has relatively good forms of grass-roots organization that incorporate young people into healthy activities," said Richard Feinberg, a professor at the University of California San Diego who advised former President Bill Clinton on Latin America.

When police and community organizations "see kids are headed in the wrong direction, they try to get them back into school, or sports," Feinberg said.

Cops work with neighborhood watch groups, many of which are still allied with the ruling Sandinista political party, said Rogers, who publishes the English-language news website Nicaragua Dispatch.

“What these organizations are able to do, though, is maintain a certain level of social control in the neighborhood," Rogers said. "They work very closely with police, and they can identify certain members of the community who are going against the program.”

Nicaraguan police are active in identifying and helping at-risk youth, Rogers added, “and not cracking down on them with heavy-handed policing policies that we've seen in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.”

Those countries have come under fire from human-rights groups for so-called Mano Dura strategies that have expanded prison populations but done little to stem gang violence. U.S. officials have called these tactics “failed.”

“Nicaragua has sort of moved away from that,” Rogers said, “and the proof is in the pudding that it's working.”

Nevertheless, in recent years, opposition parties have decried what they say is an increasing politicization of the public safety system, Rogers said, in part because government handouts often come with participating in neighborhood watch groups.

No foothold for gangs in Nicaragua

While gangs in El Salvador and Honduras force entire neighborhoods to flee, Nicaragua’s gang problems are more on the scale of the Jets and the Sharks.

“Gangs here are pretty small potatoes compared to what they are in those other countries,” Butler said.

Community policing efforts have helped keep Nicaraguan gangs small scale while local gangs in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala long ago relinquished control to transnational gangs, principally the Mara Salvatrucha and Mara 18.

Both gangs were born in Los Angeles and, according to a 2012 report from the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime, “their presence in Central America is almost certainly a result of the wave of criminal deportations from the United States to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras after 1996.”

That was the year the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act expanded the list of crimes making an immigrant eligible for deportation.

Thousands of members of the Mara Salvatrucha and Mara 18 have since been deported to El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, where those gangs have simultaneously flourished in a void of effective policing and limited efforts to reintegrate deportees into their home economies and social structures.

Not many Nicaraguans living in the U.S. got involved in those gangs, in part because there weren’t many of them living in Los Angeles. The majority of the Nicaraguan population living in the U.S. is concentrated in Miami and Northern California.

Rogers, the journalist, said transnational gangs have made efforts to establish themselves in Nicaragua, but they’ve largely failed.

“The Nicaraguan police have done, to their credit, a pretty remarkable job in identifying these guys and cracking down on them right away,” Rogers said.

More Nicaraguans in the U.S. legally

One of the few points of agreement between Republican and Democratic leaders in the debate over the latest border crisis is that cross-border family ties are a huge pull factor.

U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell recently told Congress that her agency had handed over about 55 percent of the Central American children who have crossed the border illegally in recent months to a parent living in the U.S. An additional 30 percent have been placed with relatives living here.

An estimated 2 million Salvadorans live in the U.S. and 1.2 million Guatemalans. There are only 395,000 Nicaraguans, and more than half are U.S. citizens. This compares with 23 percent of Guatemalans living in the U.S. as citizens, according to the Pew Hispanic Center.

Historically, the U.S. has made it easier for Nicaraguans to get legal status compared to other Central American countries. The Reagan administration considered Nicaragua’s leftist Sandinista government an enemy, while supporting the governments of El Salvador and Guatemala in their fight against Marxist guerrilla forces.

With fewer Nicaraguans living in the U.S. illegally, that meant not as many were removed as the U.S. cranked up deportations in recent decades. In contrast, tens of thousands of other Central Americans have become caught up in a cycle of deportation and reentry that has had far-reaching consequences, said Ev Meade, director of the Trans-Border Institute at the University of San Diego.

“You’re spending a lot of money trying to get back into the United States, borrowing money, paying smugglers,” Meade said. “But it also means you have communities in both places where kids grow up without their parents and thus they’re more likely to get into a street gang, and they’re more likely to be subject to all the coercion and violence that go with that.”

The Costa Rican dream

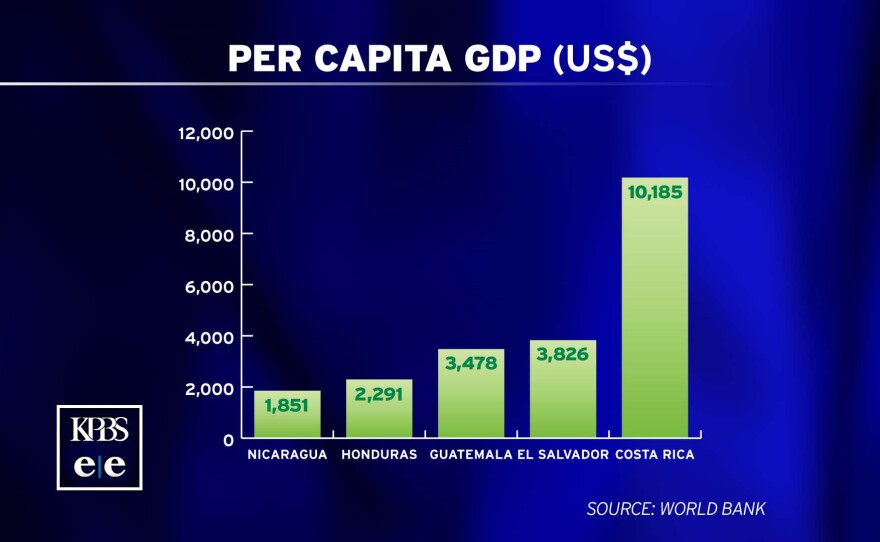

Poverty in Nicaragua does push many of its citizens out of the country, just not necessarily to the U.S.

“…authorities have built a mile-long, 8-foot-high wall to try to discourage migrants," a 2010 article in the Arizona Republic reported. "Federal police patrol the border in pickup trucks and boats. But one morning this fall, the flow of immigrants continued unabated.”

The story was about Nicaraguan migration to Costa Rica.

According to Costa Rica’s 2011 census, nearly 300,000 Nicaraguans live there. Nicaraguans have been heading across their southern border for decades in search of work and opportunities in the relatively prosperous Central American nation.

Per capita GDP in Costa Rica is $10,185, more than five times that of Nicaragua.

“Nicaraguans are sort of the backbone of the Costa Rican economy,” said journalist Tim Rogers, of Nicaragua’s neighbor to the south. Many are employed as maids, seasonal agricultural workers and construction workers.

U.S.-funded security efforts show few results

Because Nicaraguans already have an extensive support system established in Costa Rica, economic migrants are more likely to go there, Rogers said.

There may be lessons for decision-makers in the absence of Nicaraguan children flocking to the U.S. border, experts said, particularly in terms of the U.S.'s historical involvement in the region.

"There seems to be a lot of amnesia in terms of our policy toward Central America, the kinds of regimes we were bolstering back in the '80s, the kind of societies that came out of that," Gould said.

More recently, the U.S. has allocated $1.2 billion toward improving security in Central America since 2008, according to a 2013 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office. Most of those funds are aimed at Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala for efforts including drug interdiction, after-school and job training programs for at-risk youth, and training and equipment for security forces.

“Something has gone really wrong here,” said Cruz, the Florida International University professor. "The U.S.-trained institutions are the worst able to deal with crime."

The GAO report criticized the U.S. government for failing to measure the effectiveness of its efforts to improve security in Central America.

Now President Barack Obama is asking for an additional $300 million to address the root causes driving Central American children out of their countries. This is part of the $3.7 billion in emergency funds he requested to deal with the influx.

A joint statement with the presidents of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras said the countries were formulating a plan "to create the conditions that will allow the citizens of Central America to live in safe communities with access to education, jobs, and opportunities for social and economic advancement."

Cruz said, “The big question is, 'Why is this happening when we’re supposed to have stable, democratic countries?' And to the extent that we don’t resolve that, people are going to keep coming and coming and coming.”