GUATEMALA CITY, Guatemala — María, a petite, 63-year-old Honduran woman, pulled a newspaper clipping out of a folder thick with documents.

“They killed my son on Feb. 27, 2011,” she said, pointing to the photo of a young man in a wheelchair.

Gunshots during a robbery landed her son in a wheelchair several years before he was killed. Local gang members finished the job after accusing him of passing information to a rival gang.

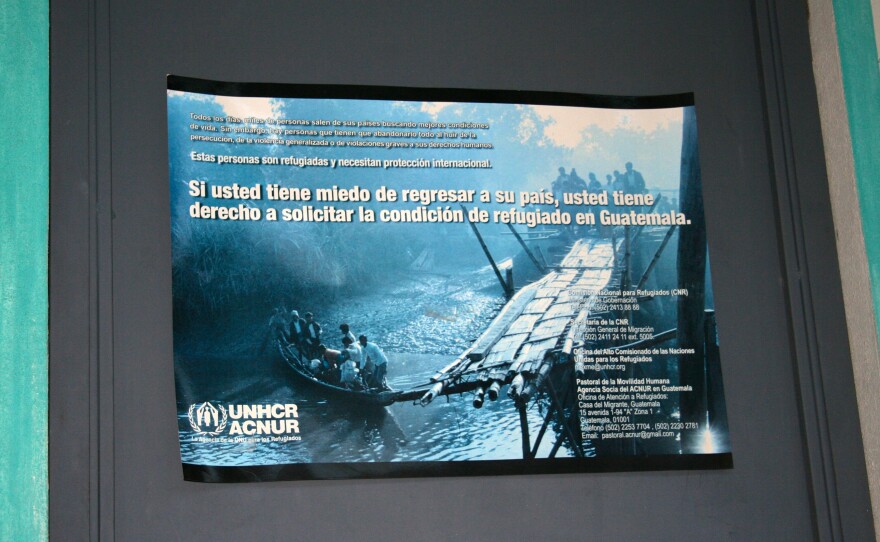

María told the story as she sat with her daughter-in-law and granddaughter at a shelter for migrants in Guatemala City.

The family didn’t want their names published for fear of retribution by their alleged persecutors.

Threats against the family continued after her son’s death, María said, so she fled Honduras in early January along with 12 family members.

Guatemala has given them temporary protected status. But the thick folder on María’s lap contains many other documents that she hopes will help her family get asylum in the U.S. or Canada.

In fiscal year 2013 the number of foreigners claiming a fear of returning to their home country when apprehended at the U.S. border more than doubled, totaling 36,026. Nearly two-thirds of these cases, called “credible fear” claims, were made by people from El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala.

At the same time, the annual percentage of apprehensions in which immigrants claimed a credible fear of return rose to 15 percent in fiscal year 2013, compared to a range of 4 to 6 percent between fiscal year 2000 and fiscal year 2009, according to recent congressional testimony from the Department of Homeland Security.

Experts say they’re not especially surprised.

“The situation in Central America has become so extreme,” said Thomas Boerman, a consultant who serves as an expert witness in many asylum cases involving Central Americans fleeing gangs and organized crime.

“The population truly lives in a state of civic helplessness in which those government entities that they are theoretically supposed to turn to for protection and support, are just unable and in certain respects unwilling to respond to the needs of the population.”

Boerman said he had interviewed police officers in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador who told him they often counseled crime victims to leave the country because they couldn’t guarantee their safety.

The sharp rise in asylum-seekers along the border has caught the attention of some lawmakers. Congressman Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.), chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, suspects fraud.

He’s held two hearings on the issue in recent months.

“Because of our well-justified reputation for compassion, many people are tempted to file fraudulent claims just so they get a free pass into the United States,” he said at a hearing in December.

Asylum lawyers and people who work with immigrants in Central America doubted that people were trying to game the system en masse. But most admit that some amount of fraud is inevitable.

"Sure, not 100 percent of people who come to the border and say they have fear will have a legitimate fear,” said Karen Musalo, director of the Center for Gender & Refugee Studies at UC Hastings law school. "But probably a good number of them do."

Boerman said the rising number of credible fear claims does put immigration authorities in a tricky spot.

“The U.S. government has a fear, and it’s not an illegitimate fear, that if it starts granting relief based on persecution by gangs and other criminal groups that these floodgates will open,” he said.

Despite the dramatic rise in credible fear claims at the border, most Central Americans still come for the classic reasons — work and family ties.

On a weekday afternoon at the migrant shelter in Guatemala, two young men from Honduras played dominoes across a plastic table in the patio.

“I’m looking for a better life,” Jose Antonio Urbina said when asked why he was headed to the U.S. “And mostly, because my family is in the U.S., my mom, my son, my wife.”

Urbina said he was deported last year after living in Los Angeles since 1998.

Currently, individuals claiming a credible fear of return to their home country must convince an asylum officer that they have a “significant possibility” of establishing an asylum claim before an immigration judge. It's one way to begin the process of filing for asylum.

Few Central Americans who apply are ultimately granted asylum: between 6 and 8 percent of asylum applications from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador were granted in fiscal year 2013, compared to near 50 percent for Chinese asylum applications,according to the Department of Justice.

Boerman, the expert witness, said it would be tragic for the U.S. to raise the bar for asylum applicants at the border.

“If there’s not a credible and reasonable fear determination that allows the person to move their case through the system, it results in an automatic deportation. And in so many instances I’m familiar with, that really is tantamount to torture and murder,” Boerman said.

Back in Guatemala, María and her family are evaluating their next move, and getting together more documentation to make an asylum claim in the U.S. or Canada.

“God knows we’re not lying,” she said. “I’ve brought evidence that we’re in danger in Honduras. Sadly we can’t live in our country anymore.”