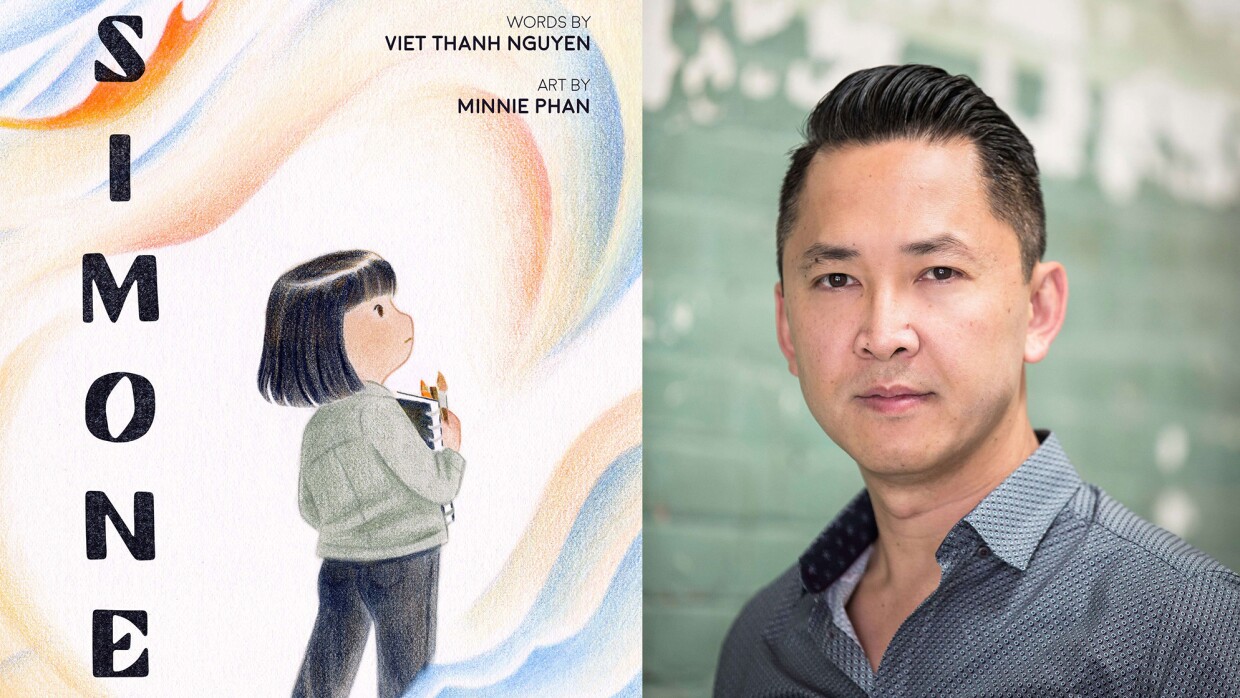

Viet Thanh Nguyen is a writer, scholar and activist. His best-selling novel "The Sympathizer" won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2016. His other works include "The Committed," the 2021 sequel to "The Sympathizer;" the short story collection "The Refugees;" and his memoir "A Man of Two Faces." His latest children's book, "Simone," created with illustrator Minnie Phan, tells the story of a young Vietnamese American girl whose life is upended by a wildfire.

Nguyen stopped by the KPBS studio last month to discuss "Simone" and his journey through identity and history.

Much of your work explores different facets of the refugee experience, and in "Simone," the main character is a climate refugee. Can you take us into the pages of the book and tell us what Simone is experiencing and this new role that she awakens to?

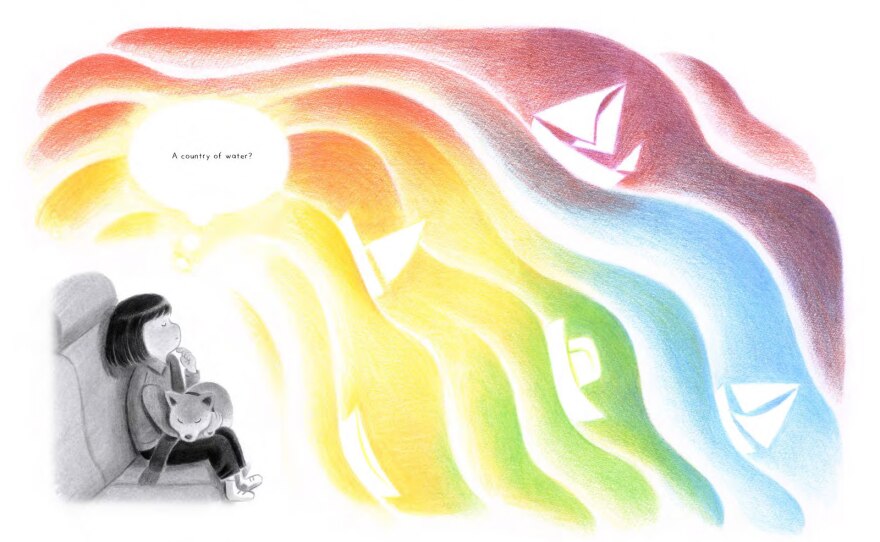

Viet Thanh Nguyen: When we meet Simone, she's dreaming. She's asleep and all of sudden she hears her mother crying, "It's time to wake up, Simone!" and she hears fire alarms. So she wakes up to I think one of the worst nightmares for many of us — as Californians, obviously, but just as people in general — this idea that all of a sudden this huge fire is coming out of nowhere and is threatening the entire neighborhood. She has to make a very rapid decision: What is she going to grab and take with her? Because they have to flee. I think this is, unfortunately, an increasingly common experience and something that we all have to prepare for — and that was the impetus for writing the book.

Is the theme of the climate something that you have explored before in your writing?

Nguyen: It actually has not. This idea came to me from the artist Minnie Phan, who illustrates this book, and she had this idea about a Vietnamese American girl confronting wildfires and I took that idea and I ran with it. I thought, what’s the opposite of fire? The opposite of fire is water. We need water, but too much water can be bad. I thought about how in Vietnam there's a lot of flooding — some really bad flooding — and so I gave Simone the character of a mother who's been through flooding in Vietnam, and now is facing fire here in California. The book is balanced between these two disasters of fire and flood, but also what they represent, in that everything in balance is part of what nature has determined for us, and Simone has to come to some recognition of that.

"How did that happen, that we all as children seem to love art, and then when we grow up as adults, so many of us have left that behind? So I wanted to explore this child's point of view, where art really does matter."— Viet Thanh Nguyen

We also see Simone find the power of art in healing. How important is art, do you think, to self-expression, especially in the face of something like the climate crisis?

Nguyen: I think many of us as adults forgot that we were all probably artists at some point. I'm the father of two young children, an 11-year-old boy and a 4-year-old girl — who’s named Simone. And what I've seen in both cases is that all the kids in their schools have loved art, they've loved creating, they love playing, they love working with color and so on and so forth. So how did that happen, that we all as children seem to love art, and then when we grow up as adults, so many of us have left that behind? So I wanted to explore this child's point of view, where art really does matter. It's something intimate, it's something natural to small children.

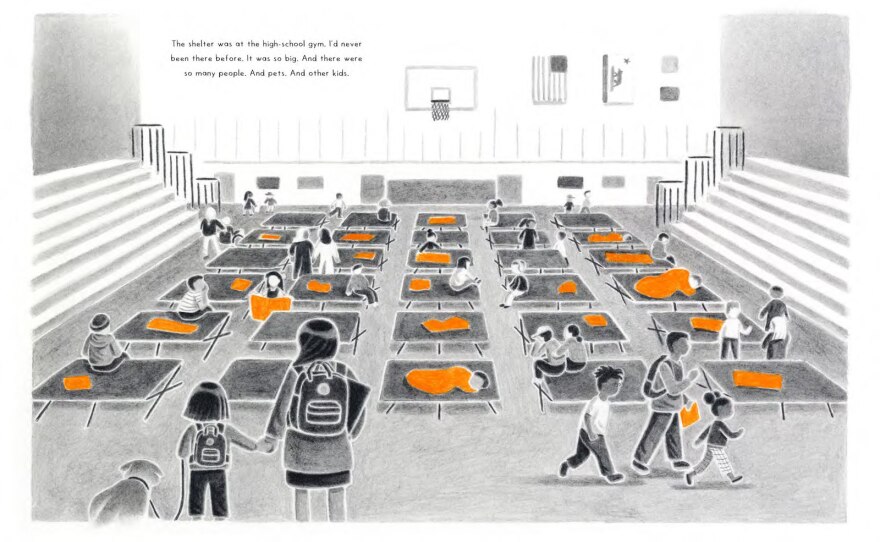

Simone ends up as a climate refugee in a high school gymnasium where the shelter has been set up. And as the adults are all freaking out, she has to calm herself down — and how does she do it? Through the pens and pencils and paper she's brought with her. And she extends that to the other fellow children who are also scared. Through that experience where she learns to take charge, she learns that art can be a way of soothing herself and these other children, but also, it's a way for her to give expression to all of these confused feelings that she is experiencing, and that, for her, it's her way of managing her fear in the face of this very difficult new reality.

"It's not the first and only instance where people have had to confront the possibility of their world ending. So, in some ways, I think refugees are already equipped to deal with this, but most Americans have never had to confront the refugee experience. Except now, as they potentially think of themselves as climate refugees."— Viet Thanh Nguyen

You have alluded to this, but climate change is worsening and extreme weather and the impacts are becoming more common. We're also seeing greater attention to the idea of climate trauma. What are your thoughts on this, and how it could impact future generations like Simone's?

Nguyen: I think climate change or climate catastrophe is certainly here. I hope there's no more denial that's happening out there, especially as all parts of the country are being hit regardless of whether they're "red" or "blue."

We have to move to a stance of both fighting against climate catastrophe, but also adapting to it as well. I actually have not heard the term climate trauma — thank you for introducing me to another horrible thing to think about! But obviously climate adaptability encompasses that. Here in California we prepare for earthquakes all the time, but now I think as a state and as a nation, we have to prepare for a variety of different kinds of climate disasters. And that would include not just a physical aspect and the financial aspect, but also, as you were saying, the emotional aspect of trying to confront what these climate catastrophes mean.

Obviously, it can be really daunting as we think about the world ending. It's not the first and only instance where people have had to confront the possibility of their world ending. So, in some ways, I think refugees are already equipped to deal with this, but most Americans have never had to confront the refugee experience. Except now, as they potentially think of themselves as climate refugees. And being a refugee is a traumatic experience, and let's hope that now Americans who oftentimes try to close the door against refugees might want to open the door to what refugees, who have already gone through displacement, what they can tell us about how they have coped with trauma.

I would like to talk about your memoir. It's called "A Man of Two Faces," and it follows your family's history from Vietnam to the United States. What was it like to unpack your own history and your memories as opposed to when you're writing fiction?

Nguyen: You asked earlier about trauma, and I have to say that I think every refugee, by definition, has been traumatized. I've never met a refugee who has not had a really terrifying story. I came as a refugee to the United States when I was 4, so I was insulated from that in a lot of ways because my parents bore the brunt of that trauma. But I experienced some of that, being separated from my parents when I was 4 years of age, for example. I survived that by looking forward constantly and pretending that I had not been traumatized. I think that was my way of coping with displacement and terror. That worked in one sense because I was able to become a functioning adult and a professional and so on. But in writing the memoir, what became very clear was that I actually had survived the way that I had by compartmentalizing the trauma — but it was there. It had been lurking, and it shaped me in ways that I never understood. As I looked back on my life in writing this memoir, I realized, oh, those moments of dysfunction in my life, those came directly from that traumatic experience.

"Most people reasonably don't want to go into their own particular locked box of trauma. If you've managed to survive, if you've managed to cope with it, a lot of people don't want to go back there. But as a writer, unfortunately — or fortunately — that's where the material comes from."— Viet Thanh Nguyen

Writing the memoir obviously was very revelatory in a lot of ways that helped me to understand myself, but it was very difficult because I had to go into that locked box of emotion that I had put away in order to move forward. And I think most people reasonably don't want to go into their own particular locked box of trauma. If you've managed to survive, if you've managed to cope with it, a lot of people don't want to go back there. But as a writer, unfortunately — or fortunately — that's where the material comes from.

You've said in another interview that part of your process included pretending to be the Sympathizer while writing about yourself. Talk a little more about that, please.

Nguyen: I think I'm best known for a novel called "The Sympathizer," which is about a communist spy, and the opening line of that novel is, "I'm a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces." So it's a merger of the spy story with an existential drama of feeling this duality within oneself. And I am not a spy — I think, but if I was, I wouldn't tell you — but I've taken the experience of duality, which I think is common for a lot of immigrants and refugees and minorities of various kinds, which I certainly experienced growing up, and I put it into the body of the spy, so that element is autobiographical. And I had a lot of fun writing that novel.

When it came time to writing (the memoir) "The Man of Two Faces," I felt that it was very difficult for me to write about myself. I didn't feel my life was very interesting and so on. So I had to create a persona. I went back to my Sympathizer and I thought, well, I'll have the Sympathizer write my autobiography. And that was the way I cracked myself open, by using a character that I had created, having that character write about me and through me, and he cracked me open enough so that I could get into myself, and then eventually have myself, finally, take over later on in the memoir.

So at that point, did you believe in your story as a memoir? What do you think makes a great memoir?

Nguyen: I think that the line between fiction and nonfiction can be kind of blurry because as I implied with the novel "The Sympathizer," it's fictional, but there is the nonfictional element of it in terms of my emotions, which is very important. Whereas with a lot of memoirs, nonfiction, you sometimes have to ask how much of this is actually fiction? I mean, how many of us pick up a memoir and believe everything that the memoir says? I mean, the memoir is going to make up all kinds of things. Sometimes that's deliberate. But oftentimes, it's accidental. We tell stories about ourselves all the time as a way of serving our own interests. And so I really had to confront that in writing this memoir — that it was, in many ways, as honest as I could be about myself, but even so, did I really know myself? It's certainly an attempt to do that, but I think I always have to be cautious and aware that there are forces at play within me that I don't fully understand.

“The memoirist ultimately has to betray themselves. That's the ultimate honesty that I think the memoir as a form demands from anybody who dares to take it up.”— Viet Thanh Nguyen

But ultimately I think what makes a memoir compelling is that we have to betray secrets. Now, it's one thing to betray the secrets of other people who never asked to be involved in your memoir — in my case, my family, for example. But in order to make that believable and palatable for readers, I think the memoirist ultimately has to betray themselves. That's the ultimate honesty that I think the memoir as a form demands from anybody who dares to take it up.

So when we read memoirs of certain celebrities, we know they're probably not fully betraying themselves. But I think the best memoirs are really where we get a sense that the memoirist is doing their best to investigate parts of themselves they never fully understood before — and that's terrifying for a lot of people. That's why when we read a really good memoir … one of my reactions to a really good memoir has always been, "I can't believe they just wrote that. Because it's so terrifying."

I love that. You just did a talk at UC San Diego, where you trace your own journey to identifying with the Palestinian cause. I'd love it if you could talk more about that journey.

Nguyen: I think it's important to talk about that kind of a connection in today's day and age, when at least in the United States, it seems as if there is so much censorship and pressure against speaking out on Palestine in ways that would contradict the stance of Israel and its supporters.

For me, the connection between Vietnam and Palestine, is that Vietnam underwent many decades of war and colonization and occupation by outside powers — with France and with the United States — and that war displaced so many people and turned so many of us into refugees. And then I got to the United States, and I became an American and I was able to tell my story in a way that Americans could understand — because Americans at least know that the Vietnam War happened and that this was a conflict within the United States. And here was a Vietnamese American coming along to tell them something about this story.

"My writing has so much been about arguing that America is a country composed of both beauty and brutality. And it goes back to the very origins. The beauty is obviously the democracy, the equality, the opportunity — all of which I've benefited from. But the beauty has only been made possible by the brutality that this is a nation that has been founded on enslavement, genocide, colonization and war."— Viet Thanh Nguyen

But the issue is, I think, that for a lot of Americans, they do not understand how much war has happened in American history. It's really amazing that we have had so many wars as Americans, and Americans cannot connect the dots. It's like, "Oh, we were in the Philippines. We were in Korea. We were in Laos. We're in Cambodia. We're in Vietnam. This is just accidental that America has fought so many wars."

In fact, you know, my writing has so much been about arguing that America is a country composed of both beauty and brutality. And it goes back to the very origins. So, the beauty is obviously the democracy, the equality, the opportunity — all of which I've benefited from. But the beauty has only been made possible by the brutality that this is a nation that has been founded on enslavement, genocide, colonization and war. And from that fundamental contradiction that defines our country, I can draw a direct line from the settlement of America to the wars in Asia, leading to Vietnam, and then going from there to Iraq, Afghanistan, Palestine.

I think it's a very clear thread of the American desire to have domination over as much of the world as we Americans could possibly want. And so, the Palestinian resistance to Israel, I think, directly contradicts the American notion that we are always on the side of democracy and freedom. We could be on the side of democracy and freedom for Israelis but that's being done at the cost of the occupation of Palestine, the suppression of Palestinian speech and the killing of many Palestinians — obviously a complex issue, but again, I think that for me, you know, my sympathy for the Palestinians comes about with a simultaneous sympathy for Jewish Americans. I grew up reading a lot of Jewish American literature, being exposed to Jewish American culture, watching movies featuring the Holocaust and so on.

I think it's absolutely right that we should advocate against anti-Semitism. We should remember the Holocaust. But if we're committed to those principles, we should recognize that there is a genocide happening now in Palestine, being committed by Israel and unfortunately by the United States government that is supporting Israel.

You were on a book tour last year, when one of your events was canceled shortly before it was set to take place and it was in response to an open letter that you had signed in the London Review of Books, calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. It's been over a year since then. Can you share your reflections on that experience?

Nguyen: It was a reflex on my part to sign the ceasefire letter, because it was a matter of principle. I'm opposed to war, I'm opposed to genocide, I'm opposed to occupation. But I was also really aware that after 9/11, the United States did exactly the wrong thing. It went into a mode of revenge, and into a series of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that took the lives of hundreds of thousands of innocent people who had nothing to do with 9/11. And I think it was very obvious in the aftermath of Oct. 7, (2023) that the chance of Israel doing the exact same thing was very, very high and that many, many innocent Palestinians would pay the price. So I thought it was absolutely important to sign this letter calling for ceasefire.

It turned out to be a very controversial letter. Of course a lot of people have been fired or silenced in various ways for taking on this cause of ceasefire. And now look at us a year later, I think it's become common sense that there should be a ceasefire. So what happened in the year in between? Was it really necessary to engage in this horrifying war that's killed at least 42,000 Palestinians? I don't think so. So it was hard, I think, for so many people to look past the reflexive need for revenge and the calls for nationalism and so on that were happening back then.

But the actor Andrew Garfield, most famous for "Spider-Man," went to the 92nd Street Y, the very same institution that canceled my talk, and he was asked on the very same stage I should have been on, What's most preoccupying you? and he said, the suffering and the deaths of Palestinians. And the world didn't end simply because someone said that on that stage.

The lesson for me from that was: Number one, I would have been happy to be on that stage on Oct. 28, (2023) and to have taken all the criticism and all the anger and all the questions and all the comments that people might have had, and we would all have been better off — and the 92nd Street Y would have been better off as well — for having had that difficult conversation. So at the very least, this whole year's worth of cancellations, suppressions and so on that have taken place — not just at the 92nd Street Y but throughout the United States, including so many college campuses, including my own (University of Southern California) — all that that has indicated is that silencing will get us nowhere. We need to have the difficult conversations and places like university campuses and culture institutions, like the 92nd Street Y and this radio show, that's the exactly what we should be doing.

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for length.