On a busy overpass in Golden Hill is something truly unique, and a contrast to the cacophony of urban sounds vibrating through this intersection.

It’s called the Crab Carillon. You may not realize it upon first glance, but it's a musical bridge just waiting to be played.

Artist Roman de Salvo created this public art installation on 25th Street in 2003.

Each segment on the song rail plays a palindrome, which means the melody is the same played in both directions. It’s similar to the way a crab walks from side to side, hence the name Crab Carillon. The melody starts and ends with a Bach-inspired C minor.

“Ultimately it's a noisy place and that wasn't fully appreciated when I came up with my concept," de Salvo said.

The bridge's red brass plumbing pipes, chosen for their durability and tunability, were cut to the right length, and then filed precisely for each note.

Twenty years later, the bridge's giant metallophone still works.

But, the project goes beyond conceptual art. The bridge was actually commissioned by the city of San Diego as a civil engineering solution to create a safer walking environment for school children.

De Salvo said from a pedestrian standpoint, trying to cross State Route 94 was a hostile experience.

“They were looking for ways to make it a better crossing for the kids, and they thought an artist was a good person to do that,” de Salvo said.

As an artist, he used the environment to exploit the linear space instead of creating something to stop, look at, or read. Using the bridge as an engine to compel people to the other side. But there is one characteristic of the rails that de Salvo was not aware of until far into the project.

Individual stiles had to be added between each note to bring the railing to city code, a detail city engineers didn’t tell him until too late.

“It’s designed against head entrapment, “ de Salvo said. “When we had to add these things here, these intermediate stiles, strumming became a situation where you also are strumming the noise of the railing.”

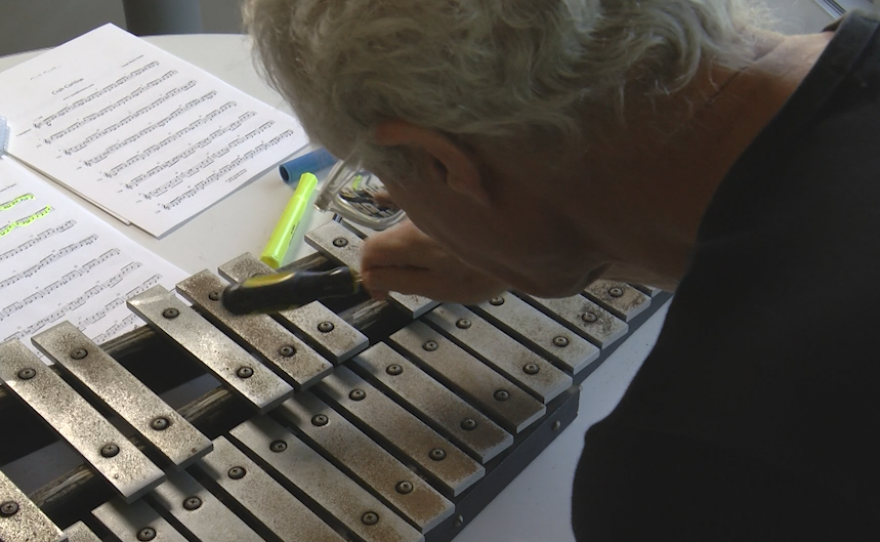

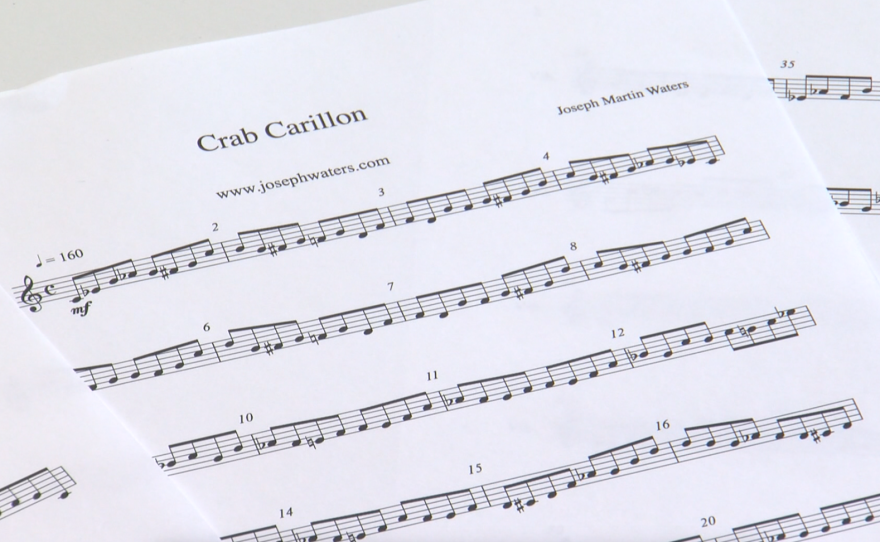

Joseph Martin Waters, a professor of music composition at San Diego State University composed the palindrome. He said the additional stiles on the railings change the music.

“In between every one of these things that makes a note, there's a thing that goes, ‘clank’,” he said.

Waters said it's like a puzzle, which feeds our fascination with patterns, and seeing patterns is exciting.

“It's better than food, it's better than sex,” he said. ”I want patterns because that's how we make sense of the world.”

He also didn’t want to make it too simple, but rather something with complexity.

“I don't want to write something that's just kind of a dumb song for kids, like something that's forgettable,” Waters said. “I wanted to write something that they can think about musically, like they can really dig into, that it has something they can discover.”

On a visit to the chime rail in 2014, Waters met some locals who brought his music to life.

“She had a big screwdriver, which looks kind of like an urban weapon,” Waters said. ”But she said, ‘I always carry this with me because every time I cross the street, I play the chimerail.’ And I thought, how wonderful to have created something that becomes part of the community.”

Waters went back to the bridge last month and said he was sad to see it in a state of disrepair, with chimes missing because of vehicle accidents and environmental wear.

But, while the Crab Carillon has been punished by the environment over the last two decades, it has also changed its environment. Much like how the concrete and galvanized steel are built to last, so is its conceptual meaning: finding art in unexpected places.