Editor's note: This story contains crude language.

San Diego is home to a world-class public art scene.

Throughout the city you’ll find colorful murals stretching across entire buildings and soaring sculptures celebrating the city’s heritage.

You’ll also find public art sprinkled along the bowels of “America’s Finest City” — from public bathrooms to pump stations to sewage treatment plants.

“We may be dealing with shit, but somebody can look at this and find something beautiful in it,” said artist Richard Turner, whose work appears on five wastewater treatment plants in California, including two in San Diego.

According to Christine Jones, chief of civic art strategies for the city’s Commission for Arts and Culture, public art is one way to “serendipitously illuminate places” that go often unnoticed by the public.

“You’d be surprised by the playfulness and the opportunities that lend itself to public art,” she said.

Public Bathrooms

Artist Shinpei Takeda offered a simple justification for putting art on public bathrooms.

“You have to look at something on the toilet,” he said.

The Japanese-born artist spoke to KPBS while standing outside a public restroom in Ocean Beach. The city commissioned him to transform the facility’s ceiling more than a decade ago.

Takeda used to live in the neighborhood, so the project was personal.

The piece is titled “My Memory on Top of Your Memory.” It features quotes from famous authors whose names appear on nearby street signs, as well as excerpts from news stories in local publications. The busy intersection of words evokes the past, present and future of this free-spirited, fast-evolving neighborhood. He designed the piece digitally, and then applied it to the ceiling as a giant, durable sticker.

“If art is something that makes us think, something that makes us reflect, I think it can be anywhere,” he said.

Stifling a laugh, he added, “And where else is better to do it (than where) you, you know, do the most biological business.”

About a mile north from Takeda’s “biological business” canvas is another public restroom adorned with city-funded public art.

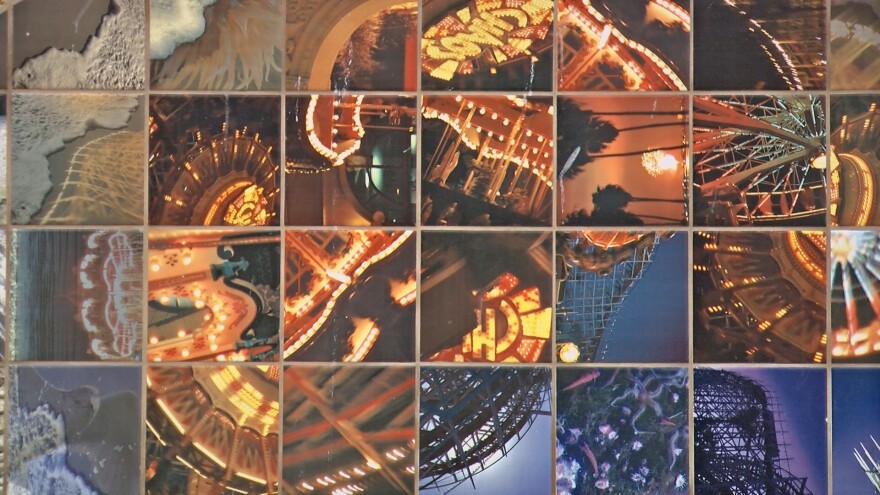

The work, titled “Pixelated Summer,” is a collage of photo tiles capturing the frenetic joy of nearby Belmont Park and the summer serenity of Mission Beach.

Artist Sarah Diana Lejeune said she took some of the photos while actually riding the Giant Dipper roller coaster. She also had her young daughter take photos of tide pools, in order to capture the “child's curiosity” of summer beach trips. Her daughter also appears in a few of the tile images.

On a recent morning, resident Jacob Bishop stopped to consider the artwork after metal detecting on the beach. The tile with the young girl jumped out, he said, because it reminded him of taking his daughters to the beach when they were little.

“I tried to teach them to surf — you know, put the leash on their leg up high because it didn’t fit,” he said with a smile. “They had their little wetsuits and it was a lot of fun.”

While public response to the artwork on these two bathrooms appears generally positive, it’s worth noting that putting art on public restrooms can come with at least a speck of political peril. In 2014, the city helped install an ornate public bathroom on the waterfront, which cost about $2 million. A few years later, when a Hepatitis A outbreak caused illness and death among the homeless population, the city faced criticism for not prioritizing basic sanitation facilities throughout the city.

Pump Stations

When you flush at these beach restrooms, the water flows to Pump Station 2 near the San Diego Airport.

Pump stations help sewage reach treatment plants, and at least five in San Diego feature public art. There’s one down the road from Pump Station 2 that’s wrapped in untreated metal lettering, which spells out a Ralph Waldo Emerson quote.

In Nestor, a pump station is surrounded by a plaza filled with towering sandstone pillars. Another one near Mission Trails Regional Park features mosaics with native stones and handmade tiles.

There are also examples in Encanto and near Los Peñasquitos Canyon Preserve.

Treatment Plants

From the pump station, our artsy effluent expedition continues to the Point Loma Wastewater Treatment Plant.

The facility is covered — inside and out — with public art. The interior features ornate walkway designs and floor mats that celebrate wastewater treatment. There’s also a photo series capturing the nearby bluffside views.

Artist Richard Turner produced the artwork on the outside of the building, including a series of abstract metal patterns. Some are a cascade of blue, green and purple, representing the ocean. Others are a mix of rusty black and brown, representing the sewage treated inside.

Turner wanted to make parts of the installation interactive, especially for workers at the plant.

“I made some tables and chairs out of manhole covers and other material that's related to wastewater treatment,” he said. “So that people would have a nice place to go out and have their lunch.”

He also included a section of pipe that people can stand inside. It’s the exact kind of pipe the plant uses to safely discharge treated wastewater — about 150 million gallons a day — into the ocean.

“I thought, ‘OK, here I've got an opportunity to actually bring visitors inside … a part of the plant itself,’” he said.

The Point Loma plant sends semi-processed “sludge” (a term of art in the industry) to the Metro Biosolids Center in Kearny Mesa, where Turner also left his mark.

The installation at the Biosolids Center is perhaps the most intricate example of public art on San Diego’s wastewater system.

The artwork starts outside the facility, before most visitors would even realize it. The large rocks around the parking lot steadily shrink on the way to the lobby entrance, which “mirrors the process of what biosolids go through as they get broken down in a wastewater treatment plant,” according to Turner.

Nearby manhole covers feature images of dung beetles — a recurring motif throughout the installation. The bug eats animal droppings and then recycles nutrients back into the ecosystem. It’s a perfect metaphor for the Biosolids Center, which turns semi-processed sludge into fertilizer cakes that are used in Arizona to grow non-edible crops.

Richard Pitchford, the Biosolids Center’s superintendent, said the artwork prompts visitors to ponder the complex process that happens after they use the bathroom.

“You flush it, it’s gone, (and you) don’t have the deal with it anymore,” he said. “Well, we deal with it on the other end, and it’s actually a fascinating industry.”

Turner’s installation explores the history of scat and sewage, from the ancient Egyptians to pre-modern plumbing. It even pays homage to a bit of San Diego wastewater trivia. Like how the city once used Fiesta Island as a giant sludge-drying bed, or how the low-flow toilet initiative resulted in a mountainous pile of discarded porcelain thrones.

The artwork also leans into the inherent humor of the topic.

“It's essential to (help) people be comfortable with what is a taboo subject matter,” Turner said.

He included an entire photo series of found objects — mostly children's toys — that were filtered out during the wastewater treatment process. If scatological history doesn’t pique your interest, maybe you’ll find amusement in the little plastic dinosaur that went down the drain after a haphazard flush.

Pitchford says one of his favorite pieces features a series of little floating logs on one of the hallway walls. The logs start out a brownish-clay color, and then slowly turn to a shimmering gold.

“I probably walked by it several times before I really figured out, ‘Oh this is what it’s representing,’” he said. “You can start out with something that is basically someone’s waste, and by the end of the process, it is worth something.”

He even found symbolism in the blank spaces at the end of the wall, where the logs disappear.

“We don’t know what the future holds for our biosolids,” Pitchford said.

That interpretation caught the artist Turner by surprise.

“I never once considered those empty spaces having any meaning whatsoever,” he said. “He is bringing meaning to that piece, and that means that the piece is working in that context. That is great. I love that.”

In the end, maybe that’s what this bathroom art is all about — finding meaning, and value, where you least expect it.

Some food for thought, the next time you hit the head.