Criteria for inclusion

- Must be directed by a Black filmmaker.

- Must feature Black cast (or, if a documentary, focus on Black subject matter).

- Must be a U.S. film (this list does not include films from African filmmakers, as that is a separate, rich category).

- Must hold significance in the history of Black film — whether by being a first, being overlooked or underappreciated, challenging status quo, tackling provocative issues, impacting pop culture or offering a new perspective.

- Must be available to watch in some form. (Emphasis is on narrative features, though some documentaries and early films may not be full-length features.)

In 2021, I posted daily for the 28 days of Black History Month to create a list of films representing a century of Black cinema. The list deserves repeating (with some updates), so here it is, arranged in chronological order and grouped by decade to provide a sense of how Black cinema has evolved.

And remember, this is just an introduction to Black cinema. The list only scratches the surface of important films, filmmakers and performers, and focuses specifically on U.S. films by Black filmmakers.

1920s

“Within Our Gates” (1920) and “Body and Soul” (1925)

Director: Oscar Micheaux

No better place to kick off a list of a century of Black films than with pioneering filmmaker Oscar Micheaux. And let's begin with not one, but two films from him.

“Within Our Gates” arrived five years after D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” and only months after the deadly Chicago race riot of 1919. It was Micheaux’s second film of more than 40 and revealed his desire to challenge Hollywood's racial stereotypes with more realistic images of Black characters and Black communities. In addition, he asked audiences to view white characters — who are shown lynching an innocent family and sexually assaulting the Black protagonist — as the barbaric savages, not the Black characters. Although Micheaux was new to the medium, and the medium itself was still in its infancy, he was trying to use it to tackle complex ideas and themes.

The Library of Congress states, “Oscar Micheaux wrote, produced and directed this groundbreaking motion picture considered one of the first of a genre that would become known as ‘race films.’ Many critics have seen ‘Within Our Gates’ as Micheaux's response to D.W. Griffith’s ‘Birth of a Nation,’ in which African Americans were depicted as generally negative stereotypes, as they were in almost all films of the day. Despite Micheaux’s limited budget and limited production values, it still effectively confronted racism head-on with its story of a teacher (Evelyn Preer) determined to start a school for poor Black children. Contemporary viewers may find it difficult to defend Micheaux’s balancing act between authenticity and acceptability to white audiences, but that’s what he believed was necessary simply to get the film made. Named to the National Film Registry in 1992."

In addition, Micheaux is noteworthy for forming the first Black-owned and controlled movie production company, and, in 1919, becoming the first African American to make a film. He was known for making “race movies,” which were films aimed at a Black audience and featuring a Black cast. He was also the first African American to produce a film shown in “white” movie theaters.

"Body and Soul" boasts the film debut of 27-year-old singer and stage actor Paul Robeson, in the dual role of a malevolent minister and conscientious inventor. The film faced severe censorship, with Micheaux cutting it almost in half to obtain an exhibition license in the state of New York, which denied him one on the grounds that his film would be “immoral,” “sacrilegious” and “tend to incite crime.” But the real reason it offended those in power was that it was a film made outside the Hollywood system by a Black man, challenging audiences to think critically.

Watch: “Within Our Gates"

Watch: “Body and Soul"

1930s

“Hell-Bound Train” (1930) and “Heaven-Bound Traveler” (1935)

Directors: James and Eloyce Gist

James and Eloyce Gist were African American evangelists who used film as a means of preaching to their traveling ministry. “Hell-Bound Train” is a cinematic allegory in which passengers board a train where each car depicts a different level of sin from the Jazz Age — dancing, gambling, drinking, music, adultery and more. Overseeing these “hell-bound” passengers is the Devil (a man in a silly Halloween devil costume). The sinners seem to be having an awfully good time, and many of the depicted sins seem tame, especially from a contemporary perspective.

Although made in the sound era, the film had no synchronoized dialogue or sound. It was screened in churches and other venues, likely accompanied by a sermon to expand on its themes. The Gists had no formal film training, and their films were crudely shot with 16mm cameras, yet the surreal quality of their allegories is fascinating — perhaps even enhanced by the childlike quality of their storytelling.

“Heaven-Bound Traveler” was designed as a follow-up film, but no complete version of it exists. What’s most impressive and memorable about “Heaven-Bound Traveler” (and to a lesser degree, “Hell-Bound Train”) is how naturally it captures some of the Black characters (including Eloyce Gist as a wrongfully accused wife). At times, it feels like it is giving us an unfiltered window into Black life in the early 1930s, a perspective rarely seen in mainstream films. For that alone, it is worth seeing. These films have also been archived in the Library of Congress. The Gists paved the way for modern filmmakers like Tyler Perry, who has also tapped into a faith-based community to find success.

Both films are available through Kino's Pioneers of African American Cinema (DVD/Blu-ray and streaming on Kino Now).

1940s

“The Blood of Jesus” (1941) and “Dirty Gertie From Harlem U.S.A.” (1946)

Director: Spencer Williams

Following in the faith-based filmmaking tradition of James and Eloyce Gist, “The Blood of Jesus” also served up a religious tale that crossed into surreal territory, complete with a devil and an angel fighting over a dying woman’s soul, and Christ speaking from the cross. Gospel music (performed by R.L. Robertson and The Heavenly Choir) powerfully drives much of the story. But like Cecil B. DeMille, director Spencer Williams spends a lot of time showing "sinful" behavior (which here includes dancing and singing) before a character repents. Williams’ film presents a portrait of Black faith and community — from baptism to death — in a manner that feels honest and sincere. The film was thought lost, but a print was found in the 1980s, and it has since been added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry. Williams also plays the dying woman’s husband.

Williams’ pioneering work in early Black film may be overshadowed by the controversy over his racially stereotyped role as Andy on the 1950s TV show “The Amos 'n' Andy Show.” But hopefully, Williams will be remembered for the more interesting work he did before he found TV fame.

In the 1930s, Williams worked in "race movies" (low-budget, independently produced films with all-Black casts, designed for racially segregated theaters). He also wrote “Son of Ingagi” (1940) considered the first science-fiction horror film to feature an all-Black cast. In 1946, he directed “Dirty Gertie From Harlem U.S.A.,” another film exploring the battle for a woman’s soul — this time with more emphasis on “sinful” singing and dancing. I am recommending it to show the range of his work, as the styles of the two films are very different. Williams also appears in drag as a voodoo fortune teller in this film.

These race movies, with their all-Black casts and sometimes Black directors, were designed to play in segregated cinemas. But by the 1950s, this separate cinema movement would come to an end, and so too, in some ways, would Black control over Black images in film. Hollywood began highlighting African Americans on screen, but Black writers and directors remained rare until the 1970s, when Blaxploitation opened new doors… but more on that later.

Watch: “The Blood of Jesus”

Watch: ”Dirty Gertie From Harlem U.S.A.”

1950s

The 1950s had some memorable films featuring strong Black characters, starting with Jackie Robinson playing himself in "The Jackie Robinson Story" to kick off the decade. In 1950, Sidney Poitier also made his debut in the film noir "No Way Out" and later that decade appeared in "Cry, the Beloved Country," "Edge of the City," "Porgy and Bess" and "The Defiant Ones." It was also a decade that saw Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte in "Carmen Jones."

But I couldn’t find any Black feature film directors of note in the 1950s. I don’t know if that’s because my research skills are bad or because Black directors found little work as segregated cinemas died out and mainstream Hollywood wasn’t ready to put African Americans in the director’s chair even when films focused on Black lives. The closest I could find were a pair of films that Belafonte starred in and served as an uncredited producer: "Carmen Jones" and the outstanding noir "Odds Against Tomorrow."

Watch: "Carmen Jones"

Watch: "Odds Against Tomorrow"

1960s

“Integration Report 1” (1960), “A Tribute to Malcolm X” (1967) and “I Am Somebody” (1970)

Director: Madeline Anderson

The 60s did not offer a lot of Black filmmakers either, but think it is worth highlighting Madeline Anderson’s 1960 documentary “Integration Report 1” (which is available packaged together with her two other remarkable documentaries). I am bending my rules a little here since she worked in television, but the scarcity of Black directors in the 1950s and 1960s, combined with her groundbreaking work, justifies her inclusion.

Anderson, who is just shy of 100, has been credited as the first Black woman to produce and direct a televised documentary film. She has said that she believes film must inspire social change.

According to the Smithsonian’s oral histories, she was "the first Black woman to direct and produce a syndicated TV series, the first Black woman to join the film editors union and the first Black employee of any gender at New York City's public TV channel WNET. Another achievement was her helping to found the first Black-owned public TV channel, WHUT, at Howard University in Washington, D.C."

Her trio of documentaries chronicles Black struggles with a perceptive, unblinking eye and a keen sense of detail. Her films remain powerfully relevant because the racism and injustice she documented still exist and need addressing.

Watch: “Integration Report 1”

Watch: “A Tribute to Malcolm X”

Watch: “I Am Somebody”

"Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class" (1968) and "Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One" (1968)

Director: William Greaves

In 1968, William Greaves made two films: a traditional journalistic documentary, "Still A Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class," and an experimental film "Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One," in which he filmed himself shooting a film. Greaves was meta before that term became popular to mean self-referential. Without the inventive narrative style of "Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One," perhaps Melvin Van Peebles wouldn't have made his audaciously experimental "Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song." Both of Greaves' films are worth checking out for their radically different styles and for the different views we get of Black life. The documentary captures the Black middle class at a moment in time and raises questions that are still pertinent today. "Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One" (to which he made a sequel in 2005) is less about Black life and more about one artist's struggle with the creative process. The fact that he's Black is not really the primary focus, which was in many ways fresh and novel.

Greaves began his career as an actor and went on to produce and direct television, documentaries and feature films. For two years, he was executive producer and co-host of the pioneering network television series "Black Journal," for which he won an Emmy. Among his other outstanding documentary films are "From These Roots," an in-depth study of the Harlem Renaissance, and "Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice."

Watch: "Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class"

Watch: "Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One"

1970s

“Watermelon Man” (1970) and “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” (1971)

Director: Melvin Van Peebles

With the dawn of a new decade, Melvin Van Peebles helped usher in the era of Blaxploitation with a pair of films: “Watermelon Man” and “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss.” The films are an interesting contrast. “Watermelon Man,” a biting satire, was made for a Hollywood studio and gave us Godfrey Cambridge as a bigoted white man who wakes up one morning to find he's Black. He frantically tries to remove his Blackness, but his efforts fail. Now he experiences racism from the other side and ends up becoming a militant Black activist. Van Peebles cleverly challenges traditional representations of Black characters. A major victory was casting a Black actor, the great Cambridge, in whiteface to play the role rather than following the traditional practice of a white actor in blackface. Van Peebles uses racial stereotypes for laughs but also for social commentary as his character eventually embraces his Blackness and becomes radicalized.

The studio wanted him to change the ending so the man wakes up white from his "nightmare" of being Black, and Van Peebles was supposed to shoot two endings, his and the studio's. But on the DVD of the film, Van Peebles said he only filmed the current ending of the movie, not shooting the "it was all a dream" ending "by accident." And since he brought the film in under budget and ahead of schedule, no one could really complain, and he got his way.

Then he chose to go completely outside the studio system to make “Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song” in 1971. It was like a seismic jolt, a Molotov cocktail tossed at the status quo and announcing a new Black indie cinema. The film was revolutionary not just in terms of being a story of a rebellious Black character written and directed by a Black man but also in terms of its free-flowing, experimental narrative style.

Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton proclaimed it, "The first truly revolutionary Black film made," while co-founder Bobby Seale urged all "brothers and sisters in the struggle" to see Van Peebles' "Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song." The Panthers even devoted an entire issue of their newspaper to the film.

Plus, when the film got an X rating Van Peebles turned it into a marketing campaign to attract audiences by proclaiming it was "Rated X by an all-white jury."

He is also the father of Mario Van Peebles, who is an actor and director in his own right. Van Peebles was as much a trailblazer as Micheaux.

Watch: “Watermelon Man”

Watch: “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song”

“Cotton Comes to Harlem” (1970) and “Black Girl” (1972)

Director: Ossie Davis

Melvin Van Peebles, Ossie Davis and Gordon Parks, Sr. were key in ushering in the era of Blaxploitation. In its heyday of the 1970s, Blaxploitation served up films for a Black audience, usually distributed by major studios, and at their best managed to cross over to a mainstream audience. These films featured African American characters who were driving the stories and the action, and they gave a number of Black directors their first chance to helm a film.

Blaxploitation was not embraced by everyone, but as author David F. Walker said, “It signaled a shift in the way Blackness was presented, a fairly significant shift in the way it was presented in popular culture, and that shift was reflective of power fantasies and desires and, in a lot of ways, the unfulfilled dreams of the '60s. I think that if you look at those films and then you look at the decade that came before and the one that came after, you can see that progression. I think you can look at a film like 'Get Out' or Marvel's 'Black Panther' movie, and I'd argue that none of those films would exist today if it wasn't for Blaxploitation, because if nothing else, what the Blaxploitation era and the movement itself did was it opened the door and created opportunities, and that door they could never shut that door again."

Released on the same day as Van Peebles’ “Watermelon Man,” “Cotton Comes to Harlem” was a landmark of Black cinema because it was one of the first to make money with a mainstream audience. Part of its broad appeal was that it was an action comedy (also featuring the great Cambridge) and fun. Davis, who was an acclaimed film and stage actor as well as a civil rights activist, adapted Chester Himes’ novel “Cotton Comes to Harlem,” which followed a pair of African American cops who played by their own rules. If social commentary was secondary to the comedy in “Cotton Comes to Harlem,” then Davis brought it more to the forefront in a film like “Black Girl,” about a young woman who wants to be a dancer despite her family’s objections. He also directed “Kongi’s Harvest,” which he shot in Nigeria, and “Countdown at Kusini” (also known as “Cool Red,” 1976), which, according to IMDb, was considered the "first American feature film shot entirely in Africa by Black professionals." His production company, Third World Cinema, was founded in 1972 to assist young African American and Puerto Rican filmmakers. The company produced “Greased Lightning,” starring Richard Pryor as NASCAR driver Wendell Scott and directed by Black filmmaker Michael Schultz.

Watch: “Cotton Comes to Harlem”

Watch: “Black Girl”

“Shaft” (1971)

Director: Gordon Parks Sr.

In 1970, “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” was a revolutionary break from Hollywood conventions, and “Cotton Comes to Harlem” proved that films with Black directors and Black casts could attract mainstream audiences. But in 1971, “Shaft” took Blaxploitation to another level by announcing a new kind of Black screen icon. In the opening shot of the film, the camera swooped down from above New York City to find Richard Roundtree’s private eye, John Shaft, emerging from the subway to cross the street against traffic and flip off the cab drivers honking at him. This was not the saintly Sidney Poitier. This was something more dangerous and in-your-face, a direct challenge to Hollywood images of Black men.

“Shaft” marked the first major studio feature directed by an African American, Gordon Parks Sr., and it helped solidify the era of Blaxploitation films that gave us new Black stars like Roundtree, Jim Brown, Fred Williamson, Pam Grier, Cambridge, Tamara Dobson, William Marshall and Jim Kelly, as well as directors such as Parks, Melvin Van Peebles, and William Crain. Parks’ directing debut came two years earlier with a much more personal film, “The Learning Tree,” and he would direct one “Shaft” sequel, “Shaft’s Big Score.”

The popularity of the film spawned two sequels, a TV series and two reboots.

Isaac Hayes became the first African American to win a non-acting Oscar with his win for Best Original Song for "Theme from Shaft."

Watch: “Shaft”

“The Spook Who Sat by the Door” (1973)

Director: Ivan Dixon

“The Spook Who Sat by the Door” is an absolute must-see in considering Black film history.

You might only recall Ivan Dixon as the token Black person in the TV sitcom “Hogan's Heroes,” but he started his career as a dramatic actor (the 1964 film “Nothing But a Man" being his best). Dixon later turned to directing with “The Spook Who Sat by the Door,” an adaptation of Sam Greenlee's novel about a man who enters the CIA as a token Black person and then uses his specialized training in political subversion and guerrilla fighting against the U.S. government.

Here's a line from the film's main character, Dan Freeman (Lawrence Cook), that might resonate today with some edge: "This is not about 'hate white folks.' This is about loving freedom enough to die or kill for it if need be." And when a riot breaks out, Freeman criticizes his Black detective friend for being there to protect property and not Black lives. The film tackles all sorts of complex ideas about how to fight systemic racism, about how people want to define their Blackness, the best ways to foster change, and more.

For the screenplay, Dixon teamed up with author Greenlee. They had trouble funding the film and when trying to shoot in the book’s setting of Chicago their permits were refused by then-Mayor Richard Daley. But Gary, Indiana, had its first Black mayor in Richard Hatcher, who welcomed the production team. The film ran out of money before shooting was complete, but footage of the riot and a sexy nightclub scene were cleverly used to convince United Artists that it could be a financially successful Blaxploitation film, so the studio picked it up. Herbie Hancock gave the film a great score.

The film drew audiences on its initial release, but pressure from the FBI (who saw it as dangerous and potentially iciting violence) caused United Artist to pull all prints from theaters, and the film essentially vanished for decades. The careers of Dixon, Greenlee and star Cook also seemed to stall. There has been a Blu-ray release, but even today, it is difficult to find streaming. This film is a powerful testament to the talents of Dixon and Greenlee, and it merits watching because so much of it is still frustratingly relevant and because it portrayed Black characters who were intelligent, compelling and unapologetically rebellious against racial injustice.

The topicality of Greenlee's novel may be getting more mainstream attention. In 2021 Variety reported that FX had ordered a pilot for a series adaptation of Greenlee’s novel with Lee Daniels ("Precious," "The United States Vs. Billie Holiday") as one of the producers. But the project stalled and I am not sure of its current status. I think someone like Boots Riley or Jordan Peele would be a more interesting creative force behind such a series, but I'm curious to see if anything comes of this.

Watch: “The Spook Who Sat by the Door”

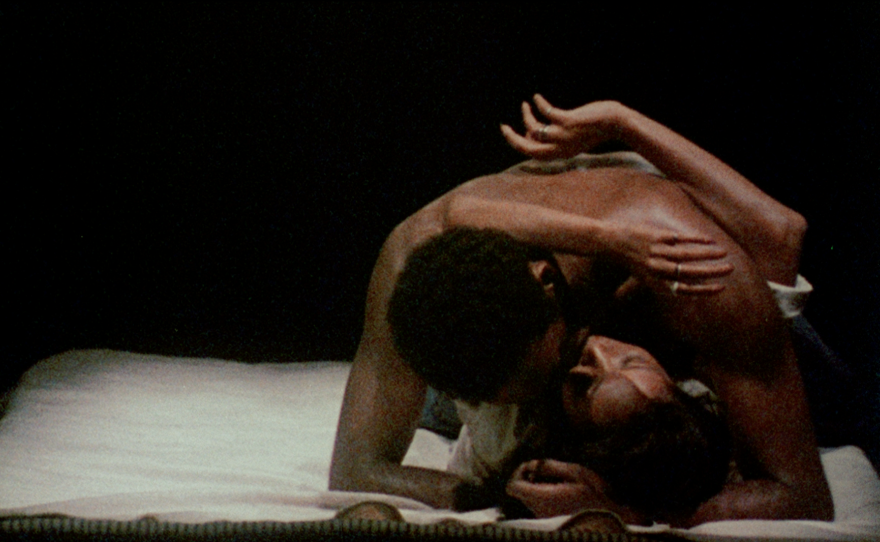

“Ganja & Hess” (1973)

Director: Bill Gunn

A year before "Ganja & Hess," William Crain directed what is often cited as the first Blaxploitation horror film, "Blacula," starring the magnificent William Marshall. It was a Blaxploitation take on Bram Stoker in which an 18th-century African prince (Marshall), turned into a vampire by Dracula (representing white colonizers), and he rises from the dead in modern-day Los Angeles. Turning to vampire lore with radically different results was Bill Gunn’s “Ganja & Hess.” The film remains as bold, original, and provocative now as it was in 1973. The film serves up a vampire horror tale featuring Duane Jones (of “Night of the Living Dead”) and Marlene Clark. As with “The Spook Who Sat by the Door,” “Ganja & Hess” had the trappings of Blaxploitation but went beyond the typical fare to deliver something richer, more thoughtful and more complex.

The film was defiantly independent, intoxicatingly allegorical, and seductively nuanced. Needless to say, that led to recutting and reissuing without Gunn’s approval to try to make it more palatable and accessible.

I think Gunn responded eloquently to the film’s mainstream critical reception in a letter to the editor he wrote in May of 1973 to "The New York Times," titled “To Be a Black Artist.” He said:

“THERE are times when the white critic must sit down and listen. If he cannot listen and learn, then he must not concern himself with Black creativity… I want to say that it is a terrible thing to be a Black artist in this country — for reasons too private to expose to the arrogance of white criticism... (One) critic wondered where was the race problem. If he looks closely, he will find it in his own review… If I were white, I would probably be called ‘fresh and different.’ If I were European, 'Ganja & Hess' might be ‘that little film you must see.’ Because I am Black, I do not even deserve the pride that one American feels for another when he discovers that a fellow countryman’s film has been selected as the only American film to be shown during Critic’s Week at the Cannes Film Festival...Not one white critic from any of the major newspapers even mentioned it… Your newspapers and critics must realize that they are controlling Black theater and film creativity with white criticism. Maybe if the Black film craze continues, the white press might even find it necessary to employ Black criticism. But if you can stop the craze in its tracks, maybe that won't be necessary.”

Do yourself a favor and watch “Ganja & Hess.”

“Dolemite” (1975)

Director: D’Urville Martin

The 70s had so much to offer in terms of Black cinema. So I also recommend Gordon Parks Jr.’s “Three the Hard Way” (1974) with the kickass cast of Fred Williamson, Jim Brown and Jim Kelly fighting white supremacists. But I could not ignore “Dolemite,” the creation of comedian Rudy Ray Moore and the directing debut of actor D’Urville Martin (who plays the villain Willie Green in the film).

Let me be clear, “Dolemite” is not great filmmaking, and some will find it offensive, but Moore deserves props for making this film completely outside the white studio system and doing it with practically nothing.

You can make fun of the film’s technical crudeness and wince at some of the stereotypes, but you will also laugh out loud at some of Moore’s comedy and be charmed by the mere fact that this film even got made and found its audience.

Moore created the character of Dolemite as part of his stand-up comedy routines. He used the character on his successful and raunchy comedy albums before deciding to put Dolemite on the big screen. He financed the film mostly with his own money and relied on friends for the cast and crew. The film was cheap and quickly made but was a financial success that allowed him to make a few more films.

"The New York Times" has called the film the "Citizen Kane" of Blaxploitation. Moore would also write, produce, and star in "The Human Tornado," "Petey Wheatstraw," and "Disco Godfather."

Watch “Dolemite” and also watch "Dolemite Is My Name," Eddie Murphy's biopic of Moore, to prep for it.

“Cooley High” (1975)

Director: Michael Schultz

Looking at the posters for “Cooley High” says a lot about its position in Black film history. One poster features a black- and-white image (which in a promo campaign suggests “realism”), and another is cartoonish art playing up the comedy. The posters seem to be trying to straddle Blaxploitation and a new age of more mainstream Black cinema. The illustrated poster art also riffs on the poster from “American Graffiti,” which “Cooley High” often gets compared to.

“Cooly High” represents a kind of bridge leading out of Blaxploitation and into Black films that tried to deal more seriously and authentically with Black life in America. Without “Cooley High” riding the periphery of Blaxploitation with a new kind of energy and style, you don’t get to Spike Lee and John Singleton.

Directed by Michael Schultz, “Cooley High” was made for under $1 million and was a box office success. The film also showcased new faces in Glynn Turman (most recently in “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom”), Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs (“Welcome Back, Kotter”), Garrett Morris (“Saturday Night Live”) and Robert Townshend (“Hollywood Shuffle”).

In an "LA Times" interview, Townshend said: “Michael Schultz really changed the landscape of cinema for people of color. He was the first one to paint with that brush of truly being human. We had never seen a movie where there was a young Black man talking about that he wanted to be a writer.”

Schultz started at the Negro Ensemble Company in 1968 and directed Lorraine Hansberry's “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” which he restaged for television in 1972. After “Cooley High,” he directed the hit “Car Wash,” "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band” (the largest budget a studio had yet given to an African American film director), then directed Pryor and Grier in the biopic “Greased Lightening” and Denzel Washington's film debut in “Carbon Copy.” Schultz is noteworthy for being a Black director Hollywood studios turned to for films not necessarily aimed at Black audiences.

Watch: “Cooley High”

“Killer of Sheep” (1978)

Director: Charles Burnett

Sometimes a film’s worth is not immediately appreciated. “Killer of Sheep” was shot in 1975 but did not receive a true theatrical release for another three decades. But this film helped define a new kind of Black independent cinema.

“Killer of Sheep” was denied wide release because director Charles Burnett was unable to get the necessary clearances for the songs used in the film. He had made the film as his thesis project while he was a grad student at UCLA’s film school for less than $10,000. The film is a bleak and beautiful look at working-class African Americans in South Central, California.

Burnett gracefully allows us to spend a few days with his protagonist Stan, getting a feel for the ebb and flow of his life. We experience the oppressive drudgery of working in a slaughterhouse; the sweet pleasure of holding his daughter; and the hunger for something more. We see small dreams snuffed out and larger ones continually out of reach. Along the way, we also get a feel for what it was like living in Watts in the mid-'70s. Burnett's film is like a time capsule that perfectly captures the details of ordinary life. Yet don't think that makes the film feel dated. Decades may have passed, but much of what Burnett has to say about the African American experience still holds true. What he saw and recorded with such clear-eyed honesty back in the '70s remains fresh, vibrant and provocative today.

The film boasts remarkable naturalism, as if Burnett just walked into Watts and started filming whatever was going on as he passed through. The images he captures have a raw honesty and unexpected poetry. His film also has an amazing innocence not only in terms of the purity of the images but also in terms of Burnett as a filmmaker. There's a quality in the film that Burnett will probably never be able to duplicate: its the innocence of being a first-time filmmaker and breaking all the rules because he doesn't yet know what those rules are.

But the film also makes us ponder how difficult it is for African American filmmakers to make serious films about their communities. Consider all the praise heaped on "Killer of Sheep" — both now and thirty years ago — yet Burnett has only made a handful of films in the decades that have passed.

The Library of Congress declared "Killer of Sheep" a national treasure and added it to the National Film Registry in 1990 for being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant."

Watch: “Killer of Sheep”

1980s

“She’s Gotta Have It” (1986) and “Do the Right Thing” (1989)

Director: Spike Lee

Here are just two of the most significant films by Spike Lee in the 1980s. “She’s Gotta Have It” was Lee’s directorial debut, and that was definitely a film that made people take note of a new voice on the cinema scene. But “She’s Gotta Have It” was a comedy, and although it was no bubble-headed rom-com it was decidedly not as serious or as angry as “Do the Right Thing” just three years later.

“She’s Gotta Have It” was noteworthy not just for the fact that Lee was a bold new Black director but also because it was a Black man acknowledging the complexity of Black women and serving up a radically fresh Black female protagonist who just wasn’t willing to conform to anyone’s stereotype or expectation of what she should be. The film was funny, original and exciting in announcing a promising young filmmaker.

And Lee did not disappoint. “Do the Right Thing” proclaimed its in-your-face social commentary from its opening frames of Rosie Perez dancing to “Fight the Power.” She was defiant, and so was the film as it looked to the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, where tensions rise along with the temperature on one hot summer day. As tempers flare and people clash, a young Black man is killed by cops and a riot breaks out. The film feels as relevant today as in 1989.

Lee has also directed great docs (“Four Little Girls”) and is still pushing himself as an artist to try new things. Recently, he made the radically different “Da 5 Bloods” and the David Byrne concert film “American Utopia.” I also highly recommend Lee’s “Malcolm X” and “Bamboozled” for Black History Month.

Watch: “She’s Gotta Have It”

Watch: “Do the Right Thing”

“Hollywood Shuffle” (1987)

Director: Robert Townsend

So far, the films I have mentioned challenged Hollywood by showing alternate Black perspectives to the ones it presented on screen. But Robert Townsend’s 1987 comedy “Hollywood Shuffle” directly challenged Hollywood itself for perpetrating those stereotypes and making it difficult for a Black actor to get a decent role.

Basing the film on some of his own experiences, Townsend delivered a biting satire about the racial stereotypes U.S. film and television presented on a regular basis. He used 10 personal credits cards to get $40,000 of the film's $100,000 budget.

Townsend plays Bobby Taylor, a young Black actor who is trying to carve out a successful career in Hollywood, but Hollywood keeps throwing obstacles in his path. Through a series of vignettes and fantasies, Townsend chronicles all the challenges he faces on a daily basis, like being told he’s not “Black enough” for certain roles. Townsend, though, did receive criticism for depicting stereotypes of his own in regards to women and gays.

But Townsend, along with co-writer Keenan Ivory Wayans, created a hilarious and pointedly accurate attack on Hollywood movies for limiting the roles offered to African American actors and repeatedly typecasting them in roles that reinforced racial stereotypes. The film still has bite today.

Townsend, who is an actor, director, producer, comedian and writer, also directed "Eddie Murphy Raw," "The Meteor Man" (the first Black big-screen superhero) and "The Five Heartbeats."

Watch: “Hollywood Shuffle”

“Tongues Untied” (1989)

Director: Marlon T. Riggs

Marlon T. Riggs’ “Tongues Untied” is an experimental documentary that strives to define a Black gay identity. The men in the film address the difficulty of expressing themselves openly while facing homophobia from Black and white heterosexuals, and racism from gay whites. The film ends by honoring those who had died of AIDS, and by comparing the civil rights movement with Black men marching in a gay pride parade.

Artistically, the film was boldly innovative for its mix of poetry, music, performance, personal narratives and archival footage. It gave voice to the marginalized Black gay community and showed Black men loving Black men as “a revolutionary act.”

The content of the film drew criticism as did the National Endowment for the Arts for providing some funding to the film and to the POV program on PBS that planned to air it.

Wikipedia quotes Riggs as saying that the film was meant to "shatter this nation's brutalizing silence on matters of sexual and racial difference." He added that the attack on PBS and the NEA was to be expected, since "any public institution caught deviating from their puritanical morality is inexorably blasted as contributing to the nation's social decay… implicit in the much-overworked rhetoric about 'community standards' is the assumption of only one central community (patriarchal, heterosexual and usually white) and only one overarching cultural standard to which television programming must necessarily appeal."

If Riggs was not the first gay African American filmmaker, then he was certainly among the first to make feature films. He was also an educator, poet and gay rights activist. He consistently challenged both racism and homophobia.

Watch: “Tongues Untied”

1990s

“Daughters of the Dust” (1991)

Director: Julie Dash

Cinema Junkie features Professor Caroline Collins talking about Black People and a Sense of Place. Julie Dash’s film “Daughter of the Dust” is one of the films we discuss. Set in 1902, this gorgeously shot, non-linear film serves up a fictionalized account of her father's Gullah family who lived off the coast of the Southeastern United States.

Collins says: “This film is about a family, the peasants who have for a couple of generations been living on a remote island off the coast of South Carolina. And historically, there were these islands where folks who were known as Gullah were able to to live in relative peace from white racial violence. They were able to carve out these lives on these islands and pass on a lot of ancestral practices and traditions that they had carried with them or that their ancestors had carried with them across the Atlantic from from West Africa into enslavement into the American South. This is following this family, but it's picking up at a really pivotal moment. They have this longstanding history of being on this island but we are smack dab at the beginning of the Great Migration and this family is going to be leaving the island and heading north to take part of this really historic moment. There is resistance from their great matriarch and it's really kind of questioning how does a family wrestle with how do you stay connected in the face of migration, both forced and voluntary?”

And these Black characters are connected to a place where there is an actual sense of ownership of the land, and now they are putting that at risk for a new opportunity but one that is still very much unknown. The film gave us characters we had not really seen on screen before and it told their story in a highly original manner.

“Daughters of the Dust” is also noteworthy as the first full-length film directed by an African American woman to obtain general theatrical release in the United States.

Dash recently announced a return to feature film directing with a biopic of Angela Davis. I hope that happens. We could use both their voices now.

Watch: "Daughters of the Dust"

“New Jack City” (1991)

Director: Mario Van Peebles

Like father, like son. There’s something satisfying about seeing Mario Van Peebles make his film debut as a child in his dad Melvin Van Peebles' “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” and then, like his dad, turn to directing. Mario even uses a clip of his dad’s film in a scene at the drug lord’s pad in “New Jack City.” Mario also paid tribute to his dad by playing him in the biopic “Badass,” about the making of “Sweet Sweetback's.”

Mario made his feature directorial debut with “New Jack City” in 1991, the same year “Daughters of the Dust” and “Boyz n the Hood” came out.

“New Jack City” turned out to be the highest-grossing indie film of 1991. The story is inspired by the real-life Detroit gang known as The Chambers Brothers. It had the trappings of an urban crime thriller/actioner, yet it also delivered a cautionary tale about drugs in poor urban communities and endowed the story with some gritty realism.

It is also noteworthy for breakout performances by Wesley Snipes and Chris Rock, and clever casting of rapper Ice-T as a cop. Plus, the online Urban Dictionary cites Rock's character as providing new slang, his name "Pookie," for opiate-based drugs like the ones his character is strung out on.

Five days before “New Jack City” was released, Rodney King was brutally beaten by Los Angeles Police officers. “New Jack City” has a scene of Ice-T’s cop brutally beating Snipes’ Nino Brown. The scene might have added sting in light of the Tyre Nichols case in which five Black cops are accused of beating him to death. The film was pulled from some theaters during its original release because of disturbances and violence surrounding some screenings in L.A. and New York.

The film opens with the line "You are about to witness the strength of street knowledge," from N.W.A.’s "Straight Outta Compton" song. It closes with the statement: “Although this is a fictional story, there are Nino Browns in every major city in America. If we don't confront the problem realistically — without empty slogans and promises — then drugs will continue to destroy our country.”

Watch: “New Jack City”

“Boyz n the Hood” (1991)

Director: John Singleton

I feel sad adding this film because “Boyz n the Hood” was such a bold debut for director John Singleton, and he died far too young (at 51), with far too much unrealized potential. I wish I was picking this knowing that Singleton was still out there making movies. But nothing can take away the historic place Singleton's "Boyz n the Hood" occupies. He started shooting it when he was just 22, and then at age of 24, he became the youngest and the first African American to be nominated for a best directing Oscar in 1992. But what is more important to remember is the impact the film itself had for its unflinching look at the lives of three young Black men in South Central L.A.

The film, as with "New Jack City," carries an added edge in light of Nichols' murder at the hands of Black cops. Singleton gives us a scene of Cuba Gooding Jr.'s character dealing with a racist Black cop who threatens to kill him, which tells us that this kind of abuse is sadly not new.

In 1997, Singleton gave us "Rosewood," a powerful dramatization of a horrific 1923 racist attack on an African American community.

Watch: "Boyz n the Hood"

Watch: "Rosewood"

"The Watermelon Woman" (1996)

Director: Cheryl Dunye

“The Watermelon Woman” follows a young Black lesbian filmmaker (played by Cheryl Dunye) who becomes fascinated with a beautiful Black actress who played a mammy character in a 1930s drama — but the credits only list the actress as “The Watermelon Woman.” This sets Cheryl on a mission to discover who this mysterious woman was.

Dunye was the first Black lesbian filmmaker to direct and release a feature. She was part of the New Queer Cinema movement of the 1990s, with “The Watermelon Woman” marking her debut film.

Dunye had a distinctive narrative style that often blurred the line between reality and fiction by employing deconstructive elements — directly addressing the camera, referencing the process of making the film and often placing herself within the narrative. She tackled issues of race, sexuality and identity.

Dunye's work includes “Mommy Is Coming,” “The Owls,” “My Baby’s Daddy” and HBO’s "Stranger Inside.” Seek out her films.

Watch: “The Watermelon Woman”

“Eve’s Bayou” (1997)

Director: Kasi Lemmons

The 90s were a great decade for Black women getting a cinematic voice. “Eve’s Bayou” is a seductive and stunning directorial debut by Kasi Lemmons.

Set in 1962 Louisiana, “Eve’s Bayou” offers a coming-of-age tale from a female perspective, and it’s a very specific, non-urban and non-poor portrait of Black life. The film centers on the well-to-do and well-respected Batiste family. Louis (a dynamic Samuel L. Jackson) is a charming and womanizing doctor married to the gorgeous Roz (Lynne Whitfield). One night, his youngest daughter, Eve (Jurnee Smollett), sees her father fooling around with a married woman. The event traumatizes her and leads to a series of lies and betrayals, as each person copes differently with deception. There’s also a contrast between the surface perfection and the flaws hidden below.

Although Jackson’s Louis is at the center of the film, it is the women who drive the story.

Propelled in part by Roger Ebert’s glowing review that named it the best film of the year, “Eve’s Bayou” became the most successful indie film of 1997. Lemmons brought a fresh Black perspective to the screen, showing audiences a story that was not about oppression or poverty but rather about Black middle-class life. It contributed to a growing multiplicity of Black identity on the big screen.

Personally, I love Lemmons' directorial debut as a visually lush, emotionally nuanced film about a young girl whose perception of her father changes radically after witnessing him having an affair. Lemmons began her career as an actress and I hope she directs more films because she has a wonderful cinematic sensibility. She brought poetry and a sense of faith to her biopic “Harriet,” and urgency to another true-life film, “Talk to Me,” about radio DJ Petey Green.

In 2018, “Eve’s Bayou” was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant."

Watch: “Eve’s Bayou”

2000s

"Training Day" (2001)

Director: Antoine Fuqua

Denzel Washington had been a major star for decades before taking on the role of Sgt. Alonzo Harris in "Training Day." The role had been offered to white actors, including Bruce Willis, Tom Sizemore and Gary Sinise. But casting Washington — who had made a career of playing noble characters ("Cry Freedom," "Glory") and romantic leads ("Mississippi Masala") — as a corrupt cop was genius. He's such a likable and charismatic actor that the audience resists realizing that he is actually the bad guy in the film. Playing against type won Washington his second Academy Award (making him the first Black actor to receive two acting Oscars). It also marked the first time an African American won the best actor Oscar in a role directed by a fellow African American, Antoine Fuqua.

Watch: "Training Day"

"Black Dynamite" (2006)

Director: Scott Sanders

As with "Hollywood Shuffle," not all films on this list have to be serious. But "Black Dynamite" is more in the vein of "Dolemite," riffing on Blaxploitation tropes and formulas. In fact, Rudy Ray Moore was a direct inspiration for some of the scenes in the film. It even spawned a TV series. It's pure fun and well worth a watch.

Watch: "Black Dynamite"

2010s

“Creed” (2015) and “Black Panther” (2018)

Director: Ryan Coogler

Ryan Coogler burst on the indie film scene with "Fruitvale Station in 2013 before moving into the Hollywood studio system with “Creed” and “Black Panther." I believe those latter films are important to acknowledge together because they show how Coogler smartly understands the Hollywood game he’s playing.

Coogler was savvy enough to see an opportunity to reimagine the “Rocky” franchise for a new and more diverse generation with “Creed.” It was Coogler's idea to create a story that would involve the son of Rocky’s first opponent, Apollo Creed. He reinvigorated the aging boxing franchise with new blood without losing any of the sentimental connections to the earlier movies or his voice as a filmmaker. With “Creed,” Coogler delivered the perfect mix of an indie drama about a young Black man coming to terms with his heritage and a Hollywood crowd-pleaser about underdogs. You could say he was clever enough to wrap his personal, indie tale in the guise of a Hollywood studio film, letting the studio think he was making its film while he was really making his own.

Without “Creed,” I’m not sure Coogler would have been chosen to direct Marvel's “Black Panther” in 2018, which became the highest-grossing film of all time by a Black director. I give Coogler much of the credit for “Black Panther’s” success. He brings the character to the screen with a savvy awareness of how to balance Hollywood’s demand for a marketable product with his own vision. In the film, Coogler cleverly cast the hero of his previous film — Michael B. Jordan — as the villain Erik Killmonger. Jordan brings a humanity to Killmonger that Coogler knew the actor had, and Jordan’s performance is key to making the film richer and more multilayered than past Marvel films. Without Coogler, I don’t think “Black Panther” would have been the cultural landmark it was. His ability to depict the differences between T’Challa and Killmonger — the former raised with a father and never experiencing oppression versus the latter’s troubled upbringing without one, dealing with systemic racism — gave the film its resonance.

I love Coogler’s ability to maintain his artistic vision even within the Hollywood industry. I look forward to what he will do next.

Watch: “Creed”

Watch: “Black Panther”

“Moonlight” (2016)

Director: Barry Jenkins

On Feb. 26, 2017, the 89th Academy Awards concluded with a dramatic mix-up that initially awarded the Best Picture Oscar to "La La Land" — and moments later — took it back to give it to "Moonlight." It was an awkward moment for the Oscars, but after the dust settled, the good news was that the better film won out. Aside from the confusion of the mix-up, the win was also a surprise because "Moonlight" was a small, independent film about a young Black boy coming to terms with his sexual identity — not the type of story the Academy tends to vote for.

"Moonlight" displayed a rapturous style and took risks in terms of narrative structure and themes. It served up a more diverse perspective than most Oscar-winning films do by inviting us to see the world through a young Black gay lens.

Regardless of what you may think of the Oscars, it was a historic win marking the first LGBTQ+ film, and the first film featuring an all-Black cast to win the best picture Academy Award. It was also the first best picture winner from a Black filmmaker, Barry Jenkins, who both directed and wrote the screenplay. He was the first African American director of a best picture Oscar winner. The first Black director with that honor was Britain's Steve McQueen for "12 Years a Slave." Mahershala Ali was the first person of Muslim faith to win an Academy Award for acting. You can criticize the Academy for many things, but an Oscar win reflects industry recognition and can translate into more tickets or Blu-rays sold.

“Moonlight” also achieved its successes with a tiny budget of $1.5 million, according to Variety. As far as best picture winners go, only “Rocky,” which cost a reported $1.1 million in its day, had a smaller budget. And if you adjust for inflation, then "Moonlight" qualifies as the best picture with the lowest budget ever.

I also highly recommend Jenkins’ “If Beale Street Could Talk,” based on a novel by James Baldwin.

Watch: “Moonlight”

“Mudbound” (2017)

Director: Dee Rees

“Mudbound” looks to two men — one Black and one white — but both living in poverty and sharing a small patch of inhospitable farmland in rural Mississippi. They are also returning from World War II to face racism and postwar life. It’s a film that has horrific violence but also a sense of hope through a friendship that defies the local bigotry.

When I saw “Mudbound,” directed by Dee Rees, I was hooked from the first frame. She displayed a mastery of image, tone and narrative that immediately put me in a place and time with such vividness that I could feel the mud beneath my feet.

She made Oscar history as the first African American woman to be nominated for the Academy Award for best adapted screenplay, and she is the first openly gay Black woman to be nominated in any Oscar category. "Mudbound" also signaled a major shift in terms of film distribution and how Hollywood was finally acknowledging industry changes. It was the first non-documentary feature film distributed by Netflix to be nominated by the Academy, which had a long-standing bias against the streaming model. But it likely lost in all four of its nominated categories because some of that bias still existed. (Netflix would win its first acting Oscar with Laura Dern’s best supporting actress win for “Marriage Story.”)

Watch: “Mudbound”

“Get Out” (2017)

Director: Jordan Peele

Jordan Peele’s feature directorial debut announced a bold new talent. Peele came to horror by way of comedy, and that proved to be a remarkably apt path. Both horror and comedy are about timing and building up tension that can be released by a laugh or a scream. His astute sense of timing and pacing allows him to use humor at exactly the right moment to give us an ever-so-brief break from our anxiety. But to be clear, this is a horror film with occasional moments that spark laughter. It is not a horror-comedy or a comedy of any kind.

“Get Out” was fueled by a desire to deliver not just a different kind of horror film but to provide a point of view that mainstream audiences had not really had the chance to experience. Peele served up not just a Black protagonist who doesn’t die in a horror film but a film that conveyed an entirely Black perspective on American society. It was a horror film about race in America, and it had a lethal edge of satire as well.

This film inspired the creation of college courses, including UCLA’s class called "Sunken Place: Racism, Survival and the Black Horror Aesthetic.” About the Sunken Place (the terrifying place the film’s protagonist goes when put under hypnosis), Peele said, “The Sunken Place means we're marginalized. No matter how hard we scream, the system silences us."

In March 2017, The Wrap reported: “Over the weekend, ‘Get Out’ director Jordan Peel quietly made history when he became the first African American writer-director to earn $100 million with his debut movie.” He was also the first African American to be nominated for producing, writing and directing in the same year. He won the Oscar for best original screenplay. Peele also became the fourth filmmaker to receive Academy Award nominations for producing, directing and writing for a debut feature film (following in the footsteps of Orson Welles). His sophomore feature, “Us,” is also innovative and provocative. Both films get better with each viewing as you discover new layers of meaning. And last year, he gave us another provocative film, "Nope." I can't wait to see what he does next.

Watch: “Get Out”

“Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse” (2018)

Co-director: Peter Ramsey

In 2012, Peter Ramsey became the first Black director of a major Hollywood animated film when he made "Rise of the Guardians" for DreamWorks. In 2018, he co-directed “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse” with Bob Persichetti and Rodney Rothman. The team won both a Golden Globe and an Oscar for best animated feature. Ramsey became the first African American to be nominated for and to win an Oscar for best animated feature.

The film was not just significant for the behind-the-scenes presence of Black artists but also for giving audiences Miles Morales, a Spider-Man who is a Black Puerto Rican kid. Ramsey was thrilled that the story promoted the idea that anybody can be behind the mask. He told the press after his Golden Globe win, "We all felt deeply the idea that anyone can have this kind of experience. Anyone can share in this myth, be in this kind of legend, be this kind of hero.”

Plus, the film kicks ass. The animation style is fresh and innovative, and the script is exceedingly well crafted. It captures the spirit of the Marvel comic, dishes up clever fun and even develops genuine emotion, so you find yourself really caring for these characters. I have to confess — this is my favorite Marvel superhero film.

Watch: “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse”

"Sorry to Bother You" (2018)

Director: Boots Riley

Boots Riley has had a long, successful career as a rapper and music producer. Now he’s added film director to his credits with “Sorry to Bother You.” Riley, in his writing and directing debut, delivers a film that he describes as “an absurdist dark comedy with magical realism and sci-fi inspired by the world of telemarketing.”

Riley’s film feels like a direct descendent of Melvin Van Peebles’ 1971 film “Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song.” Van Peebles' film had audacity not just in terms of its story and perspective but also in terms of its artistic style, which still jolts a contemporary audience. I mention this because the feeling that Van Peebles’ film generated is the same feeling I had seeing “Sorry to Bother You” — like I was seeing something boldly new, that I was witnessing a fresh, original talent.

“Sorry to Bother You” may be Riley’s first film, but he comes to filmmaking after decades of success as a rapper, music producer and activist-organizer. Plus, he had studied filmmaking back in college but got pulled away from film by music ,and in 1991, created the political activist hip-hop group The Coup.

His film deals with race, capitalism, workers’ rights, art and activism, but in ways that you have not quite seen before. In addition to the genre-bending Riley does, there’s also a different tone to the satire and social commentary. Oftentimes, a filmmaker will condemn and criticize the character that sells out, but Riley tempers his criticism with surprising compassion.

I had a chance to interview Riley and here’s a reason his tone is different: “I think that’s because I have a background as an organizer, which is different than an activist. Because to be an organizer and doing things like grassroots organizing, you get people in their place of work or place that they live and trying to do thing around those areas. That sort of a thing, doing that makes you approach politics less from a standpoint of you don’t agree with me so, therefore, you are on the other side of the line than trying to figure out, 'OK, you don’t agree with me, how do I get this person to agree with me? How do I get them on my team?' I would be working against my ultimate goal to just try to show that person that they are wrong and smash them down in some way because my goal is to have the working class united.”

But it’s precisely that tone that makes you look at issues with new eyes and with a new sense of how to challenge the things you don’t agree with. “Sorry to Bother You” is art activism that is not merely critical but tries to empower you with tools to think of new ways to voice dissent.

“Sorry to Bother You” takes some wild artistic risks and lets the story spin into unexpected territory, but the payoff is rewarding. Riley not only has something to say, but he has the artistry to say it in a fresh, new style that demands attention.

Watch: “Sorry to Bother You”

2020s

"Ma Rainey's Black Bottom" (2020) and "Time" (2020)

Directors: George C. Wolfe/Garrett Bradley

When I initially did this list, I concluded with a pair of then recently released films from 2020, the pandemic year: "Ma Rainey's Black Bottom" and "Time."

I wanted to end with a pair of recent and very different films. “Ma Rainey's Black Bottom” represents a film adaptation of August Wilson’s play and Denzel Washington’s commitment to bringing the playwright’s 10-play cycle to the screen with a mix of young filmmakers and Broadway directors. George C. Wolfe is a veteran Broadway director who also has some films under his belt. The film expands the play beautifully but also recognizes when to just let Wilson’s words take center stage. It’s also a story, like many of Wilson’s, that acknowledges the past and reminds us that while we need to move forward, we must remember where we have come from.

As a contrast, I wanted to also highlight a documentary from a young filmmaker that gives us a glimpse into the future with the potential of fresh voices. Garrett Bradley creates a uniquely cinematic documentary with “Time.” Bradley became the first Black American woman to receive the Best Director award at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. I could have also included actress Regina King's stunning directorial debut with "One Night in Miami" and Nia DaCosta's savvy reimagining of "Candyman."

Watch: “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom”

Watch: "Time"

Closing out the century

Since I made this list four years ago, many films have been worthy of inclusion. I would highlight the 2022 documentary "Is That Black Enough for You?1?" by culture critic and historian Elvis Mitchell, which offers a very personal take on Black cinema. Ava DuVernay garnered attention in 2014 for "Selma" but I think delivered even stronger work with "13th" (2016) and "Origin" (2023). Other strong women directors making their mark this decade include A.V. Rockwell ("A Thousand and One"), Raven Jackson ("All Roads Taste of Salt"), Chinonye Chukwu ("Till"), D. Smith ("Kokomo City") and Janicza Bravo ("Zola").

In the past year, RaMell Ross' "Nickel Boys" earned some surprising Oscar nominations; Denzel Washington continued to produce August Wilson's plays for the big screen with "The Piano Lesson"; and artist Titus Kaphar made his feature film directing debut with "Exhibiting Forgiveness."

Coming in 2025: Ryan Coogler's vampire tale "Sinners"; Mark Anthony Green's "Opus"; and Questlove's documentary about Sly and the Family Stone, "Sly Lives."

There is so much hope and potential on the horizon that it is truly exciting. It has been a both troubled and inspiring century of film, and I hope you will seek some of these films out. And again, this list only scratches the surface.