This past weekend, I celebrated Lunar New Year with my family, and it reminded me how much I miss my grandfather, who loved to share stories about celebrating the holiday in his homeland of China.

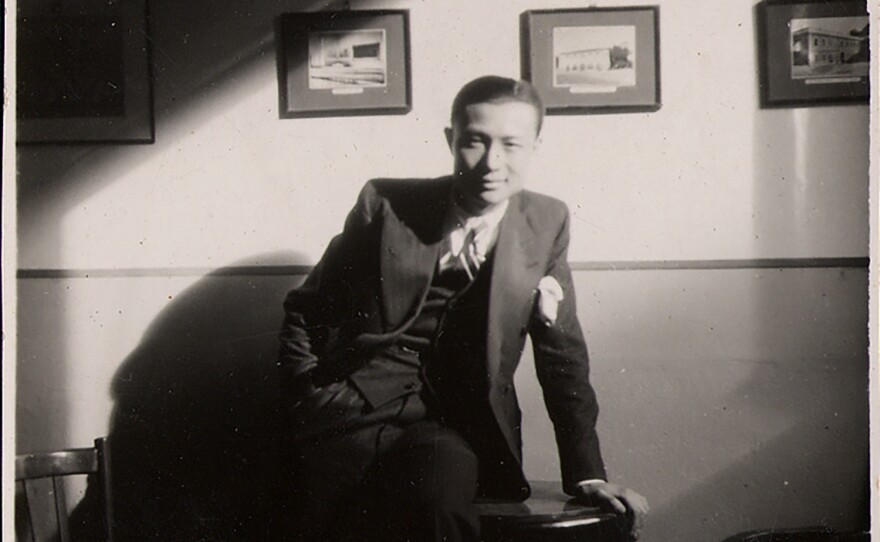

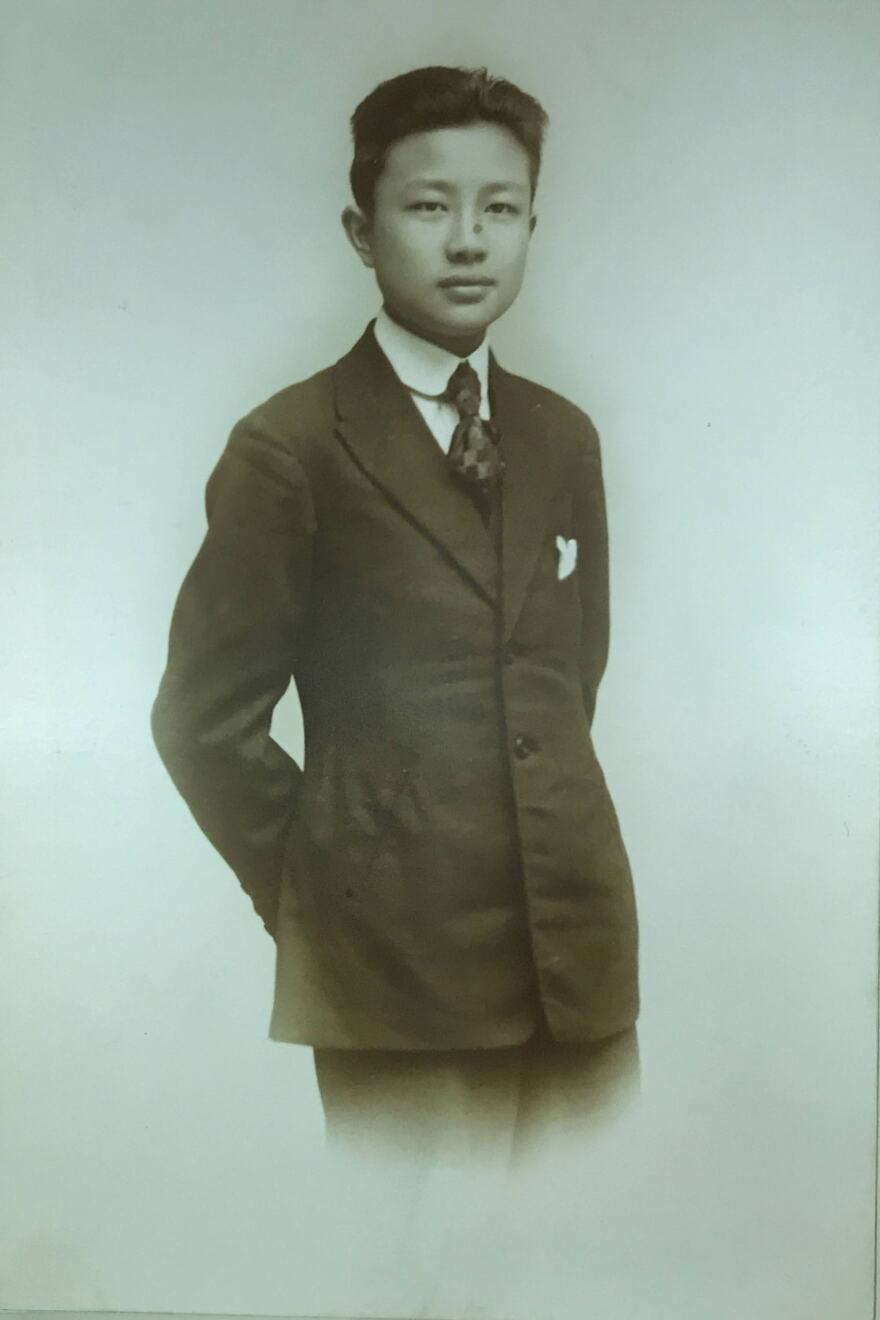

Three years ago, PacArts asked me to participate in their video program called Share Asian Joy, in which they had people tell stories about family and culture, especially ones involving elders. I spoke about my grandfather, Dr. Fuyun Hsu, and his love for celebrating Chinese New Year. You can see the final video below.

My grandfather loved to celebrate any occasion with a grand flourish. But Christmas and Chinese New Year were the BIG events. They demanded that family come from all parts of the globe, food be made in epic quantities and the 'Big Spin' be brought out.

The Big Spin is not a traditional part of either holiday but a creation of my grandfather, whom we called Papa. All year long, he would collect little prizes, and on these holidays, we would spin the prize wheel my uncle built and choose prizes wrapped in numbered paper bags. This could go on for hours, but it was something that brought him absolute delight.

Papa was the grand patriarch of my family, and he lived to be 100 years old. He squeezed in one last Christmas before dying on Dec. 27, 2005.

Hsu was born in Wuxi, China, in 1905 to a family that included pioneers in science, technology and education. He traveled to France in the 1920s and met my grandmother, Nicolette Laloy, while they were attending law school in Paris.

Papa was involved in the Scouts de France, and I now wish I had asked him about being the only Chinese member of that organization.

He began a diplomatic career as a member of the Chinese delegation to the League of Nations in Geneva. But after World War II, he began working with the newly created United Nations and served as interim chief of the Child Welfare section, during which he laid the groundwork for the creation of UNICEF.

![Dr. Fuyun Hsu, of China, Executive Secretary of the UN Scout Club, instructs the boys on the international scope of the Scout Movement. [No exact date]](https://cdn.kpbs.org/dims4/default/e0c5bae/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1200x739+0+0/resize/880x542!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fkpbs-brightspot.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com%2Ff5%2Ff8%2F20ba60034502a7ce7627276c6bb9%2Fun7477545.jpeg)

In his last assignment at the U.N., he was deputy resident representative and worked in the U.N. Development Program (UNDP) in Africa.

Papa was many things, but I think he would have loved working in the performing arts. He wrote constantly and loved overseeing public performances. He wrote short plays, some inspired by Chinese folklore, and made his tai chi class — which he taught into his 90s — and family members perform them. I sewed Mulan costumes, and my young son performed in Papa's plays. He was thrilled when given a tai chi sword and told he could perform martial arts for the production. My mom and aunts were also pressed into duty to find or make props.

Chinese New Year was always a joy. As I grew up, I loved trying to make epic Chinese meals — there had to be one dish prepared for each person coming — that would please and impress him. He was an excellent chef, and I learned many things from him, although I have still not mastered seven treasures rice. He bought my son and I cookbooks. When he liked something, he would often exclaim, "Bravo!" That always made me happy.

He shared the traditions he grew up with — and maybe some he invented,like the Big Spin. But he would always fondly point out that in China, the celebration lasted for weeks and included what he called an "orgy of gambling."

I remember buying new clothes, preferably red, each Chinese New Year to symbolize a new start — but also so you could fool the gods into not recognizing you if you had done something bad the previous year.

I miss Papa tremendously. Holidays are not quite the same anymore. People do not come from all over to pay a visit to the grand patriarch, and the Big Spin has not been seen in years. But the joy he brought to everything and the sense of epic celebration are memories I cherish — and qualities that I strive to maintain.

In the late '90s, he wrote about his memories of celebrating the Lunar New Year in China when he was a child. Here is an excerpt.

"New Year in My Childhood" by Dr. Fuyun Hsu

When I was a young, I lived in China, mostly in Shanghai. My favorite holiday was the Chinese New Year, which lasted 15 days. During these days the shops were closed but they were not empty. Inside, people played gongs, drums and cymbals. With all this music and rhythm, when you walked in the street you didn’t feel lonely.

Fireworks

“Bomb” firecrackers and “string” firecrackers broke loose all day long. "Bomb" firecrackers were made of strong paper that was compressed into cardboard cylinders stuffed with gunpowder. The largest were about the size of Quaker oats boxes. When you lit the fuse of such a firecracker, it would explode. First there was a “boom” and the firecracker was forced into the air. When it reached its highest point there would be a second explosion. You would hear a loud “pah” and the firecracker shattered into pieces. The loudest explosions sounded like real bombs, and the most powerful projectiles could reach a height of some 45 to 50 feet. It was breathtaking to watch these rockets rise and disappear into the air…and what suspense after you heard the “boom” to anticipate the “pah”. You had to watch out though because they were pretty dangerous.

The “string” firecrackers were lots of fun for children. These consisted of hundreds of little firecrackers the width of straws but only an inch long. They were connected by their fuses and braided together. When you lit the end of the braid these firecrackers went off one after another in a hundred little explosions. You had to be careful not to be hit by one because it would hurt for a few seconds. Chinese children hung the firecrackers to a tree and rushed away before the explosions. Or else they held one end of a bamboo pole and tied the braid at the other end so as to keep the explosions away from them.

When evening came, there was more fun. Fireworks went off at every corner making the streets sparkle with brilliant colors. Magic bouquets of flowers appeared and disappeared, there were orchids, chrysanthemums, May flowers and bamboo leaves. High in the air scenes from Chinese legends took place. Among them we saw the Nine Dragons drawing water from the ocean and releasing it over the earth in the form of whirling cyclones.

Decorations

Before the arrival of the new year, the house was to be cleaned and decorated. Of course, multicolored garlands were to be hung everywhere. The preferred colors were red and green.

The Chinese were believers in luck. They attributed an important role to luck in a man's successes and failures: luck in fortune, luck in business, luck in career promotion, luck in love. Although they admitted luck was somewhat predetermined, a person still could act to favor good luck and avert bad luck. One of the ways to turn the tide was to use the Taoist magic formulas (fu zhou). Our cook who claimed to know these formulas drew all sorts of conglomerate and peculiar characters on a piece of red paper and stuck it at the kitchen door and the service door. But we claimed not to be superstitious. And our front door needed something more artistic, more poetic and literary. When father was at home, he would write a poetic couplet on a pair of red scrolls to be stuck onto the two leaves of the double door.

The Ceremonial

The ceremonial rituals began on the 23rd day of the 12th lunar month. That day was the day of the ascension of the kitchen god to heaven. The kitchen god was the family god and had the function of protecting the family and watching over its behavior. Once a year, on the 23rd day of the last month of the year, he ascended to heaven and reported on the conduct of the family for which he was responsible. So early on that day a good meal was offered to him and mother worshiped. And very important was the very sweet and sticky dessert -- a sort of nougat, served with the meal. Not only was this dessert supposed to please (or to bribe) the god but to glue his mouth so that he would not be able to tell unfavorable things about the family.

Dance of the dragons

During the fifteen days we enjoyed every minute of the new year. Before going back to school, we still had one last consolation: The dance of the dragon. Traditionally it took place on the 15th of the first month -- as the grand finale of the new year. Aside from this, it did not have a special significance, except that the dragon was for the Chinese, a respected almighty legendary animal.

For the purpose of the dance, the dragon might be longer or shorter, from 20 to 10 meters. The body was puffed out each two or three meters by a half-hoop hoisted up by a dancer, by means of a rod. The dancer was thus half hidden in the body of the Dragon. Depending on the length of the dragon, the number of dancers might vary from fifteen to five. The first dancer held the head of the dragon and led the dance. The head of the dragon was impressive. It was huge, with an immense mouth, two big round eyes, a large and flat nose and long hair. Hundreds of small bells were attached to it to mark the rhythm.

The dance went like this: One dancer, independent of the dragon, held a pole at the end of which was fixed a big translucent ball, lit from the inside. It was called "hydrangea ball" because of its shape and decoration. This dancer would move this ball in all directions, and the dragon would follow the ball, in all its movements in an effort to catch it. This would produce an impression of hide and seek or of a fight between the dragon and the ball. The dance was emphasized and dramatized by the rhythmic sound of drums and gongs. While the huge head of the dragon would chase the hydrangea ball closely, and try to swallow it, all the dancers followed the movements, one after another, in such a way as to engage the long body in a swirling, graceful dance.

And when all the celebrations were over we had to return to school.