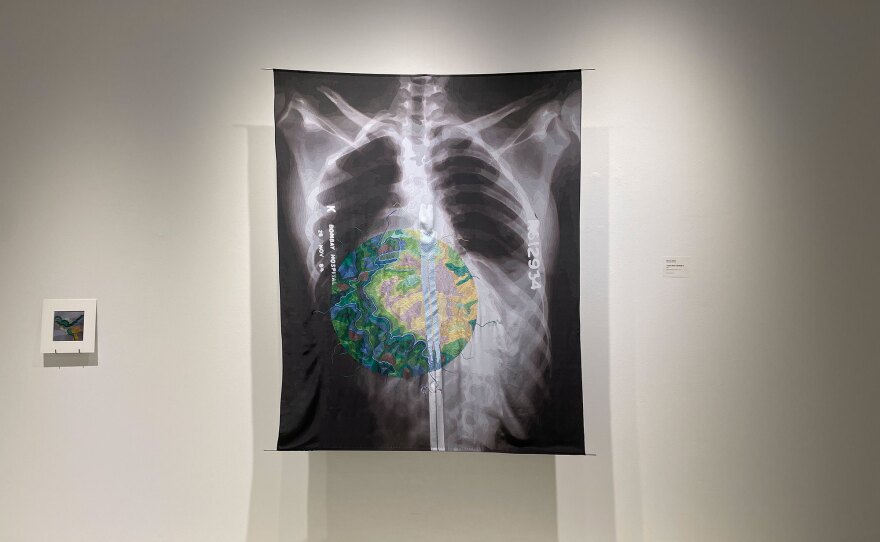

San Diego artist Bhavna Mehta carried a set of childhood X-rays with her for nearly 40 years, moving with her from India, and then from house to house in adulthood. Now, they're transformed into art for a new exhibition at San Diego State University's Art Gallery, "Script/Rescript."

Mehta was sickened with polio when she was seven. The X-rays were taken before and after a major surgery to help the severe scoliosis she'd since developed, and the "after" imagery shows two starkly bright and straight metal rods contrasted with her curved spine.

Several years ago, she began to embroider brightly colored thread directly on the X-rays.

It's an act of what Mehta thinks of as "rescripting" the script of disability.

"I think about it as extending the narrative of the X-ray. So yes, the X-ray shows disease and a body that is not so symmetrical," Mehta said.

The X-rays also show medical intervention — the two metal rods inserted into her body. Embroidered onto the image are brightly colored beads that also look like plants, vines, or renderings of the polio virus. Mehta's own interventions are her way of (literally) threading a broader personal story into the X-ray's singular snapshot of disability.

When a motor neuron is attacked by a virus, Mehta explains, the virus enters the neuron, multiplies, and when the neuron is destroyed, that specific motor function is lost.

"I don't know how many hundreds of neurons were destroyed when I lost function in my legs and my hips. But this is the process — this is a very natural process. So I'm braiding nature-related ideas with personal story, and really trying to place the human body in nature," Mehta said.

'Where is disability?'

The exhibition at SDSU is curated by Amanda Cachia, and includes art by ten artists with disabilities. An art historian, curator and critic from Australia, Cachia is a lecturer at SDSU, Cal Arts and elsewhere, and identifies as a physically disabled person.

"Working in the art world for many years, 22, 25 years now at this point, I just felt like I would never see much representation of disability in the art world. As a young intern at galleries, I was just like, 'where is disability?'," Cachia said.

Cachia estimates that the last time a San Diego art space held an exhibition of works exclusively by artists with disabilities may have been in 2016, with "Sweet Gongs Vibrating," a tactile-friendly show she curated at the then-San Diego Art Institute (now ICA San Diego) in Balboa Park.

On Bhavna Mehta's work, Cachia said that while Mehta is turning something not considered beautiful (the X-rays) into something beautiful, the aesthetics aren't the point.

"It was about empowering herself. Like, looking at images of herself that maybe she might have found uncomfortable, she turned into much more comfortable — comforting," Cachia said.

Reclaiming narratives

Such rescripting is an approach she's seeing more of amongst contemporary disabled artists, she said.

"To get whatever information they are given visually from the medical industrial complex, from hospitals, doctors, and then try and empower themselves by using that imagery for their own end."

Another local artist, Akiko Surai, also has work in the show, including embroidered, clear acrylic panels that explore neurology and traumatic brain injuries. Sugandha Gupta is an artist that Mehta said is also of Indian origin and uses embroidery, albeit in a different way. Gupta's works are tactile in nature and accessible to viewers with limited vision or blindness — visitors are encouraged to touch the embroidery.

Massachusetts-based visual and performance artist Dominic Quagliozzi's work is often autobiographical, revolving around his chronic illness, cystic fibrosis. Seven years ago, he had a double lung transplant, and his experience in hospitals and the medical system informs his art.

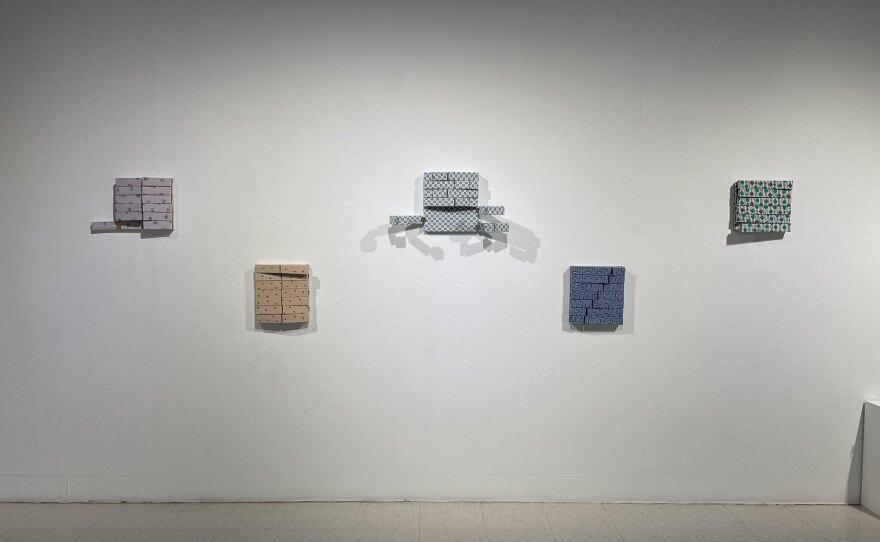

One of Quagliozzi's pieces in the show is a wall sculpture consisting of multiple paintings on hinges, that can move like limbs or body parts like limbs. Instead of canvas stretched across a wooden frame, each piece is made from hospital gown.

"The 'paintings' have obvious associations with opening up a body and revealing things. Some of them look like rib cages when they're opened up," Quagliozzi said.

His work is tactile; visitors can pull each piece and rearrange the sculpture. Part of this is accessibility — finding ways to experience art in a way other than just visually. It's also a way of reclaiming his own experience.

"We're taught not to touch artwork. Go into a museum, you shouldn't touch it, you shouldn't get too close. But my whole experience as a person with a chronic illness is doctors and nurses coming in and touching me and moving me and surgeons cutting me open and all this kind of interaction with my own body. And I wanted to try to bring that into the work," Quagliozzi said.

Chun-Shan (Sandie) Yi has a striking, suspended seaweed-like sculpture, "Kelp Help," where the shapes of the kelp mirror the shapes of the two fingers she was born with on each hand.

"I just love that she's using her body as a way of designing something that is quite natural. Seaweed. So she's also trying to refute, like, 'my hands are actually not disfigured or atypical or abnormal," Cachia, the curator, said. "I really like that a lot, that nature is kind of supporting her and saying, this is a different script. This is a rescript."

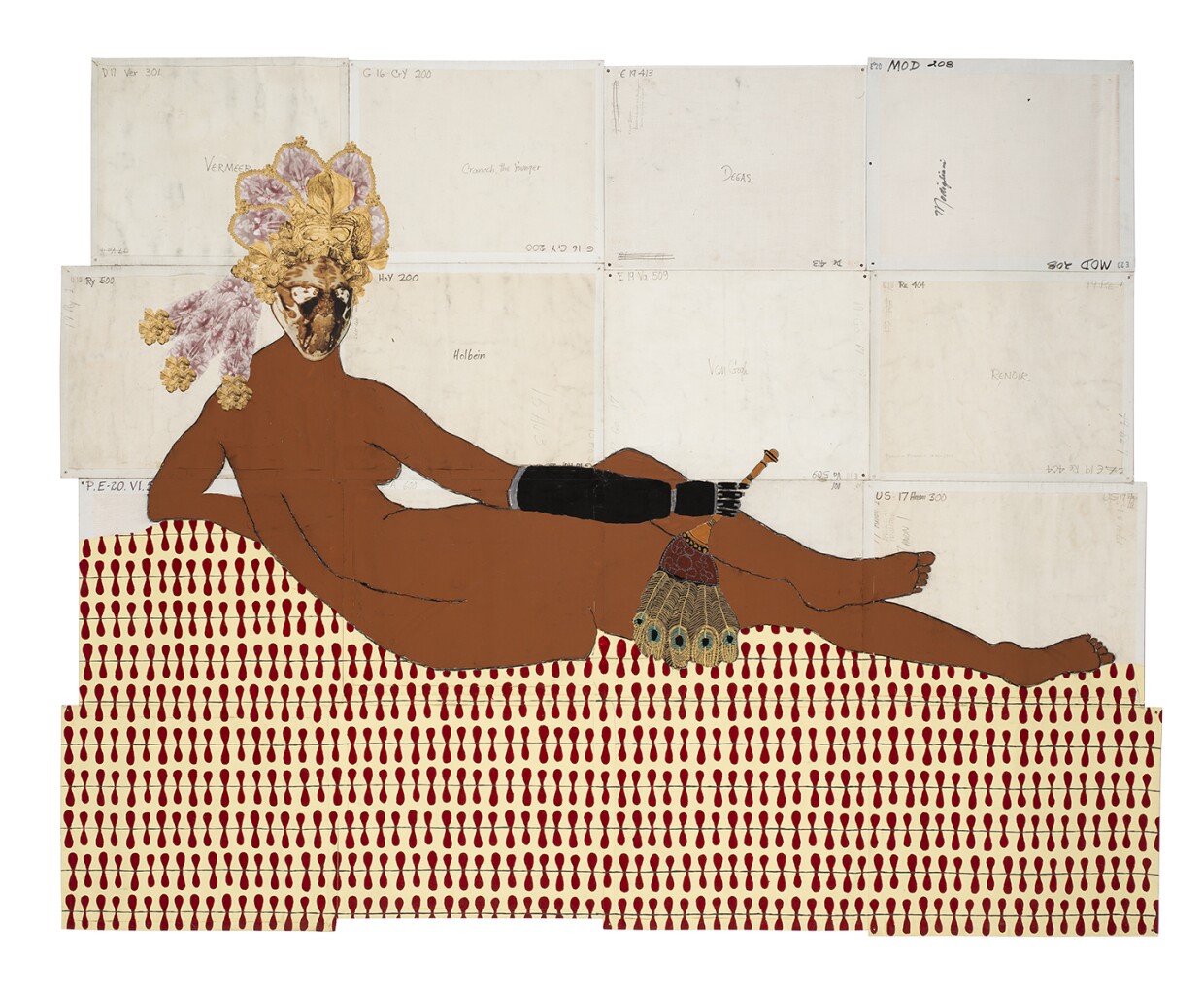

The first thing visitors will see when entering the gallery is a series of large collage and painting works by Katherine Sherwood. These pieces co-opt the canon of painting but "rescript" disability into the works. On the flipside of reproductions of old master works by Vermeer, Cezanne, Degas and others, Sherwood paints Renaissance-style reclining nudes but with a cane, a prosthesis or a partially missing leg.

"So that is a rescript less to do with the medicine actually, and more to do with art history. I thought that was a really important entry point into the show," Cachia said.

Cachia says the transformations in this show are a blend of play, imagination and truth.

"It's hard to deny truth if somebody, a disabled person, is telling you, 'This is how I feel.' So that's why it is empowering, because they're talking about their own lived experience of disability, which is unique to every single body," Cachia said.

"Script/Rescript" also features work by Panteha Abareshi, Jillian Crochet and Ana García Jácome. It opens with a reception from 4-7 p.m. on Oct. 13 and will be on view through Dec. 8, 2022 at the SDSU University Art Gallery.