The first special exhibition in the newly renovated Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (MCASD) in La Jolla is a comprehensive look at a single decade in Niki de Saint Phalle's career.

Saint Phalle lived in San Diego for approximately a decade — from 1992 until her death in 2002.

San Diegans know the French-American artist for the colorful, outdoor sculptures she made late in her career: the "Nikigator" climb-on sculpture outside the Mingei International Museum; UC San Diego's iconic "Sun God"; "Coming Together" near the convention center; and even an entire sculpture garden, "Queen Califia's Magic Circle" in Escondido.

But the MCASD exhibition reveals a Niki de Saint Phalle most San Diegans don't know: the radical and feminist work she was making in the 1960s, often grappling with her own hidden pain from an abusive childhood.

"These are early works, made 1959 to 1971 that come out of a tradition of abstract expressionism and that show her kind of collaging roots and her move towards more participatory, celebratory feminist work," said Kathryn Kanjo, the David C. Copley director and CEO of MCASD.

RELATED: Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego in La Jolla reopens to the public

The exhibition follows an evolution of Saint Phalle's work, rooted in the assemblages she made in the earlier part of the decade, through her series of "Tirs" or shooting paintings (also assemblages), and to the transition to large-scale feminine forms in her "Nanas" sculptures.

Assemblages

Saint Phalle was born in France and raised in New York City. She returned to Paris as a young adult, ultimately moving back and forth several times after she married her first husband, the American poet Harry Mathews and began to raise their two children. By 1961, they'd separated, and she began a relationship with artist Jean Tinguely.

Jill Dawsey, senior curator at MCASD and the exhibition's co-curator (with Michelle White of The Menil Collection in Houston), said that Saint Phalle was part of the nouveaux réalisme movement in art.

"This is a group of avant-garde artists — it includes Arman and eventually Christo and others — and it's kind of like the French answer to American pop," Dawsey said.

Experimenting with found objects and appropriating consumer culture were some of the foundational ideas of the nouveaux réalists. Saint Phalle's assemblages, early works in the exhibition are her assemblages, which are sculptural collages of real, everyday objects, often plastic toys.

'Tirs': Saint Phalle's shooting paintings

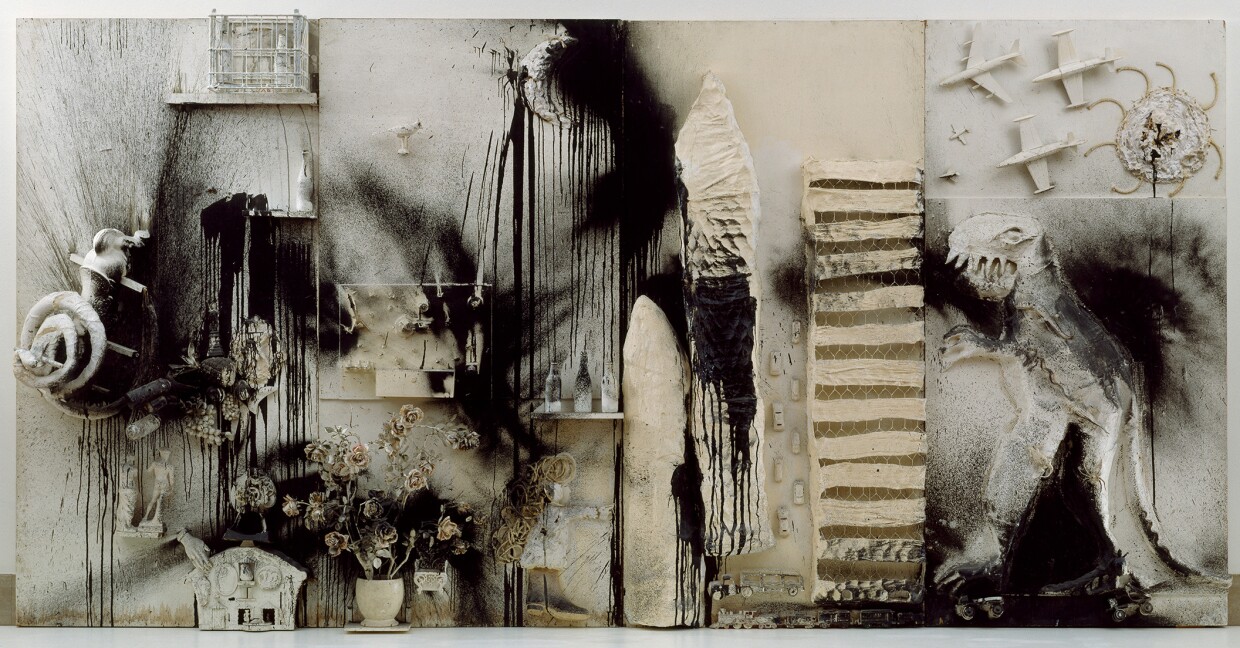

Saint Phalle expanded on her assemblage process when she embraced a more performative and participatory way of working: the "Tirs" series, or her "shooting paintings."

Saint Phalle constructed each work and concealed bags of paint before covering it all with white plaster. In some works, like "Pirodactyl over New York," on view at MCASD, she'd also embed cans of spray paint, their outlines still visible in the finished form.

Then, usually with an audience, she'd use a borrowed .22 caliber rifle to aim for the bags and spray cans of paint, meticulously but violently exploding pigment across the works.

"I think there's so much going on with the shooting paintings because on the one hand, they are a reinterpretation of abstract expressionism. They invoke this American cowboy figure, but they also reflect this larger political context of the time, and the Algerian fight for independence and the suppression of that in the streets of Paris at the time, and also the larger context like the Cold War," Dawsey said.

In the preparation for this exhibition, first unveiled at The Menil Collection in Houston last fall, the curators compiled a chronology of the shooting sessions, which adds to the body of scholarship about Niki de Saint Phalle.

Dawsey said that as the "Tirs" progress, they become larger, more fantastical with depictions of giant monsters, and take the form of tableaux. Despite only making her shooting paintings for three years, Dawsey said there were at least 25 shooting sessions that they know of.

Tucked in the back of the show alongside a collection of fascinating ephemera, notes and sketches, the exhibition includes some footage of the shooting sessions with some powerful narration by Saint Phalle.

"1961, I shot against Daddy. All men: small men, big men, tall men, fat men. Men, my brother, society. I shot against my school, my family, my mother, all men, Daddy. I shot against myself."

'Art really did save her life'

Rob Sidner, executive director and CEO of Mingei International Museum, worked with Saint Phalle over the course of her time in San Diego. The Mingei's founder, Martha Longenecker, was a close friend of Saint Phalle's, and a smaller, complementary exhibition, "Niki and Mingei" will also open at their Balboa Park museum this weekend.

By the time she arrived in San Diego, Sidner said she'd worked through a lot of her past trauma and childhood sexual abuse, primarily through this evolution in her art.

"I don't think maybe a lot of San Diegans know that piece. They've seen the results of the work she did through art. She often said that her art had kept her from killing somebody and that it had helped her to work through her great anger," Sidner said. "We saw mainly her joyous work, the 'Nanas' and all the color. I think most people think of Niki as a joyful artist, a playful artist, and may not realize what she worked through and how art really did save her life."

The 'Nanas'

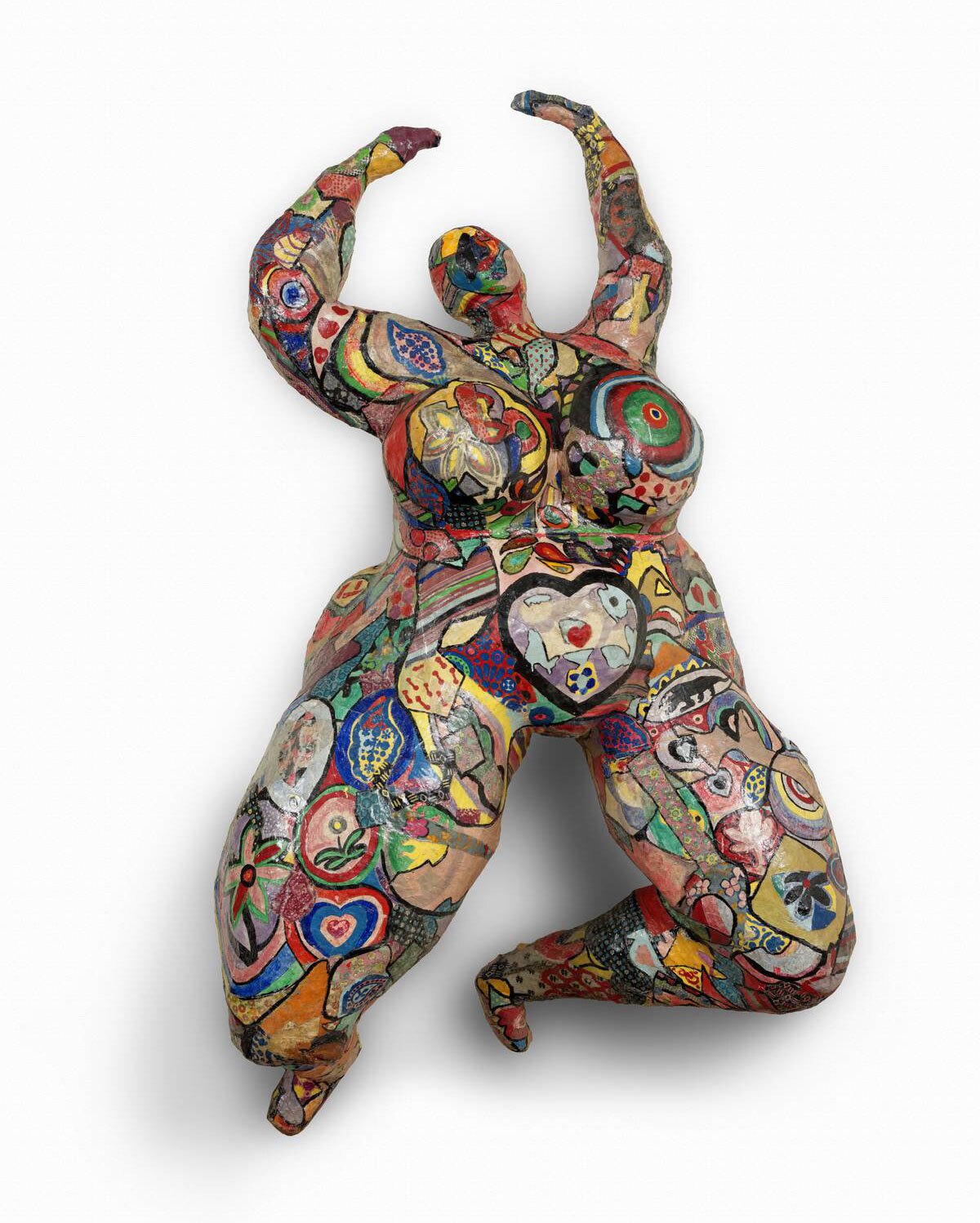

Towards the mid-1960s, Saint Phalle moved from the "Tirs" to the Nanas sculptures, which would then later seem to evolve into the more recognizable figurative sculptures Saint Phalle made towards the end of her career.

"At first, her representations are these archetypes of femininity and in some ways somewhat tortured figures, or at least conflicted figures — a bride that is immobilized by her huge wedding dress and veil and is ghostly in appearance, and witches and monsters and just all these different mothers, birthing figures," Dawsey said.

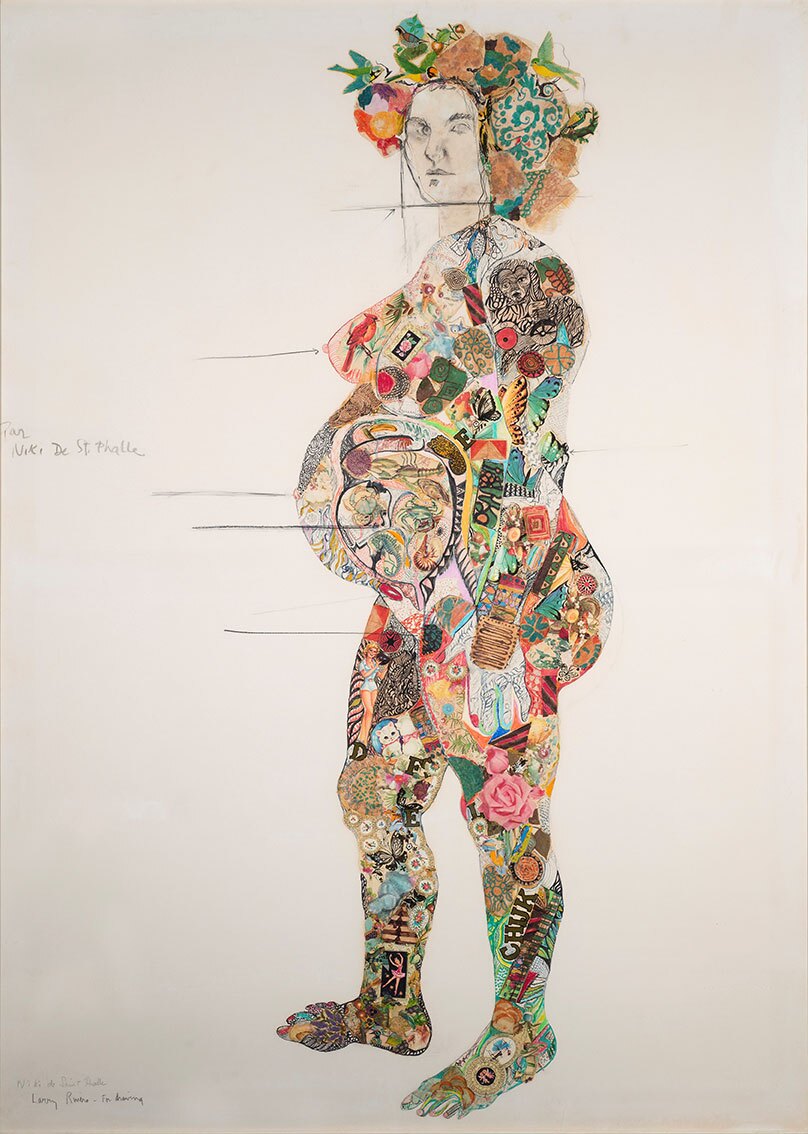

A pivotal point in the "Nanas" series, Dawsey explained, is a collaboration between Saint Phalle and artist Larry Rivers, a massive collaged portrait of his pregnant wife Clarice Rivers.

"It's this incredibly vibrant image. And from there, she has this kind of revelation," Dawsey said.

Her "Nanas" transform to reflect how Saint Phalle is embracing female joy as a sort of political act — an empowered and revolutionary way of looking at womanhood, with larger-than-life and exaggerated sculptures of feminine forms, with round hips, breasts and bottoms.

Long overdue study: 'It's just incredible how ahead of her time she is'

Saint Phalle's peers were almost exclusively male — many of whom quickly rose to international acclaim, though Saint Phalle is "under-studied," according to Dawsey.

"I think she is more celebrated for her later work, and in particular, San Diegans know the work that is around us, and so this is an opportunity for everyone to encounter just really how radical, how experimental and how influential her early work is and was," Dawsey said.

Dawsey pointed to the plentiful experimentation and progression throughout Saint Phalle's entire career but especially in the 1960s.

"She produced so much at this time that you can follow this trajectory in her thinking, and really just that she's working through these ideas, and in quick succession, and doing these things that women five to ten years later — in the context of the feminist movement, particularly in the United States, do," Dawsey said. "She's working in this masculine context and arriving at many of the same ideas. It's just incredible how ahead of her time she is."

"Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s" will be on view April 9 through July 17.