—The Fascinating History of a Uniquely American Form of Entertainment—

This four-hour, two-part documentary, explores the colorful history of this popular, influential and distinctly American form of entertainment, from the first one-ring show at the end of the 18th century to 1956, when the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey big top was pulled down for the last time.

A transformative place for reinvention, where young women could become lion tamers and young men traveled the world as roustabouts, the circus allowed people to be liberated from the roles assigned by society and find an accepting community that had eluded them elsewhere.

Drawing upon a vast and richly visual archive, and featuring a host of performers, historians and aficionados, “The Circus” brings to life an era when Circus Day would shut down a town, its stars were among the most famous people in the country, and multitudes gathered to see the improbable and the impossible, the exotic and the spectacular.

“There’s nothing in the world like a circus,” said ringmaster Johnathan Lee Iverson. “You cannot come to a circus and still believe as you previously did. Circus is a peek into what we could be, how great we could be, how beautiful our world could be. It’s about making your own miracles, conjuring your own miracles. We’re coming for the transcendent.”

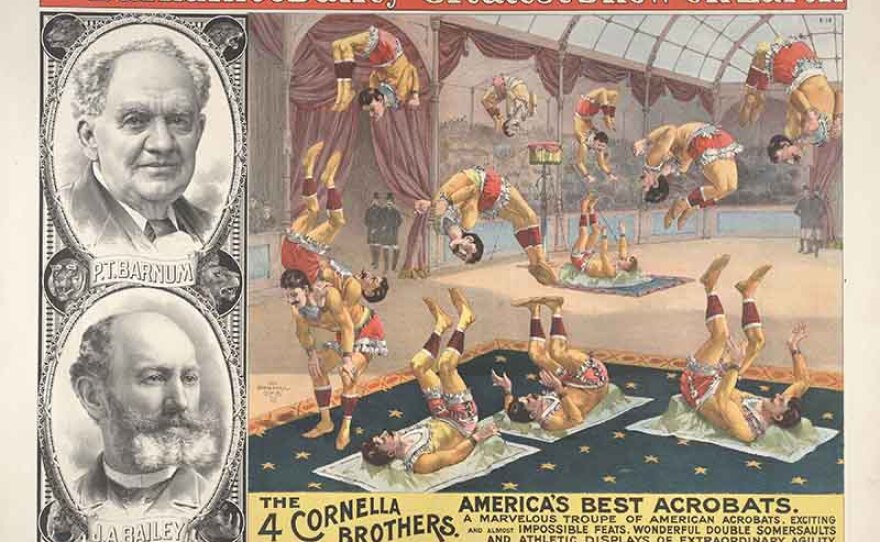

Through the intertwined stories of several of the most innovative and influential impresarios of the late 19th century, including P.T. Barnum, James Bailey and the five Ringling Brothers, the series reveals the circus as a phenomenon created by a rapidly expanding and increasingly industrialized nation.

It explores how its “dangerous” and “exotic” attractions revealed the country’s notions about race and Western dominance, and shows how the circus subverted prevailing standards of “respectability” with its unconventional, titillating and “freakish” entertainments.

“The tented traveling circus is an American creation,” said Mark Samels, executive producer of AMERICAN EXPERIENCE. “Appealing to both urban and rural parts of the country, and to people from all walks of life, the circus helped forge a common national culture and identity. It was an unprecedented combination of cutting-edge marketing, military-like organization and supreme artistry. The circus was where you could reinvent yourself, which is why so many ran away to join it. With the recent closing of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, the series offers a fascinating look back at this form of entertainment.”

EPISODE GUIDE:

Part 1 (1793-1891)

For more than a century, Circus Day was as anticipated as Christmas and the Fourth of July. It would crash into everyday life, colorful and brash, and then disappear, leaving many dreaming of another life.

As the country grew, so did the circus, evolving into a gargantuan entertainment that would unite a far-flung nation of disconnected communities and dazzle not only Americans, but the world.

The first circus in the U.S. was established in Philadelphia in 1793, but it wasn’t until the introduction of the tent in 1825 that the circus became a truly roving art form that could reach the tiniest hamlets.

“What the tent show did,” said historian Janet Davis, “was establish the rituals of itinerancy, the one-night stand, the ability to go into country that is essentially bereft of infrastructure. What the tent established was this way of circusing that became distinctly American.”

Almost everywhere, the circus met the disapproval of the religious and puritanical. In a society that valued sobriety and hard work, a wide-eyed day peering at half-naked aerialists amid shifty circus workers was frowned upon.

Soon, circuses began to add elaborate menageries of exotic animals including lions, hippos and elephants, and “human oddities” from across the globe — rebranding themselves as “educational” experiences to concerned communities.

The arrival of infamous showman and huckster P. T. Barnum transformed the trade. In 1871, Barnum and his partners created the largest touring show in existence.

In a few short years, they added a second ring to the big top and began touring by train, turning the circus into a complex, industrialized organization.

A master of publicity, Barnum promoted his shows with ever more elaborate marketing campaigns.

Other circuses followed suit, but Barnum met his match in two outstanding rivals: a former Philadelphia butcher named Adam Forepaugh, who countered every one of Barnum’s claims with outlandish hyperbole of his own, and James Bailey, who ran away to the circus at age 13 and soon owned his own show.

In 1876, Bailey would take that circus — animal menagerie, performers, tents and all — on a 76,000-mile tour around the world.

Barnum soon realized he would do better with Bailey as a partner than as a nemesis, and in a wild publicity stunt involving a baby elephant, the two men made much of their merger.

In Baraboo, Wisconsin, five sons of an impoverished immigrant harness-maker launched their own one-ring circus.

In just a few years, the Ringling boys from Baraboo had turned their show into a force with which to be reckoned.

Part 2 (1897-1956)

In 1897, James Bailey decided to take his circus to Europe on a five-year tour. When the show paraded through British streets for the first time, throngs of people turned up to watch – and the scene was repeated in towns across Europe.

“The spectacle of how the circus operated proved to be endlessly fascinating for European audiences,” said historian Matthew Wittmann. “It garnered interest even from the Prussian military. They showed up to see how the operation worked.”

Bailey returned to the U. S. in 1903 and died three years later. Soon after, the Ringling brothers bought Barnum & Bailey.

For a while, they ran the two shows separately, but, in 1918, after several tough seasons during World War I, the brothers combined their circuses into one mammoth outfit: the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, a moving town of more than 1100 people, 735 horses, nearly 1000 other animals and 28 tents.

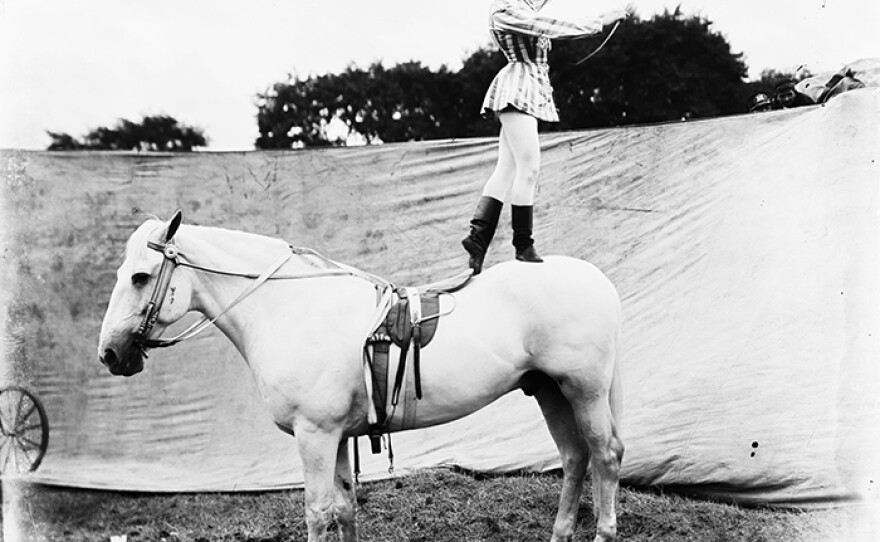

Featured were some of the most storied circus performers in history, including the famed aerialist Lillian Leitzel; May Worth, who stunned audiences by somersaulting on horseback; and big cat trainer Mabel Stark.

In an era when women were still fighting for the right to vote, women circus performers stepped to the forefront of the suffrage movement.

“The circus is a space where women did have opportunities that were unavailable in other areas of American life,” said Davis. “Top headliners were paid just as well as their male counterparts. The circus offered women a life of independence and freedom from the watchful eyes of communities and family members.”

The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus limped through the Great Depression, facing new competition from radio, sporting events and the movies.

After the death of John Ringling, the last surviving brother, his nephew, John North, took over.

North’s vision of a modernized circus that borrowed from the aesthetic of Broadway and Hollywood revived the circus for a while, but a catastrophic fire in 1944 made the operation of a massive traveling tented show unviable.

In 1956, North folded before the end of the season, announcing that his traveling circus would never again perform under a big top.

For more than a century, the circus had brought daily life to a standstill. Shows took over rail yards. Parades clogged Main Street. Acres of billowing canvas appeared mirage-like on the outskirts of town.

And then, when day broke, the miracle had vanished. Equestrians, sideshow performers, clowns, roustabouts, an enormous collection of curious beasts — all became just figments of a glorious dream.

WATCH ON YOUR SCHEDULE:

Watch the full program on the series website, PBS website or stream on demand with the PBS Video App.

JOIN THE CONVERSATION:

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE is on Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr, and you can follow @AmExperiencePBS on Twitter. #AmericanExperiencePBS

CREDITS:

Written, Produced and Directed by Sharon Grimberg. Editor, Part One: Jon Neuburger. Editor, Part Two: Mark Dugas. Co-Producer: Melissa Martin Pollard. Associate Producers are Heather Merrill and Daisy Schmitt. Composers: Gary Lionelli and Nathan Halpern. AMERICAN EXPERIENCE is a production of WGBH Boston. Senior Producer is Susan Bellows. Executive Producer is Mark Samels.