This April 30 will mark the 40th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, an event that marked the end of the Vietnam War. Unlike World War II, which most Americans saw as a well-defined battle between good and evil, the Vietnam War was not so clear-cut.

A look back on 50 years of films from the United States and abroad reveals that we are still struggling to come to terms with that divisive conflict.

During World War II, Hollywood produced mostly what could be described as benign propaganda films (“Air Force,” “Destination Tokyo,” "Back to Bataan," “They Were Expendable”) depicting soldiers as heroes, the war as just, the enemy as evil, and America’s involvement in the conflict as necessary.

There were also films produced during the war and after that showed war was hell (“G.I. Joe,” “Twelve O’clock High”) and that soldiers could come back changed (“The Best Years of Our Lives”) but there was a general sense of patriotism and there wasn’t any pervasive sense of criticism about the U.S. having gotten involved in the conflict. The same could be said about the majority of Hollywood films produced during the Korean War and depicting that conflict.

But films about the Vietnam War were different for two reasons.

First, the war itself divided the U.S., and there was a strong and vocal anti-war movement at home and abroad. After the war ended, the U.S. had the added difficulty of not being able to claim a win.

Second, the Hollywood studio system — which represented the establishment in the entertainment world just as the U.S. government was in the political sphere — was breaking down as the war began and by the 1970s, there was a vibrant independent film scene where filmmakers felt freer to speak their minds and to go against the establishment of both the studios and the government.

So here’s a look at the films made in the U.S. about Vietnam, and how themes and ideas developed in the years following the end of the war. There is also a section on foreign films (including ones made in North and South Vietnam) that offer different perspectives on the war, and on documentaries dealing with the war.

Prologue to war

Briefly, there are films that look to events leading up to the Vietnam War. Films such as “China Gate” (1957, USA), a typical Hollywood melodrama where romance takes the front seat to the French Indochina War and uses Vietnam as a setting simply because it was exotic. Angie Dickinson plays a Eurasian woman without much credibility but she looked good in the Asian dresses and that’s really all the studio cared about. But the French were making more serious films like “Patrouile de choc” “Shock Patrol” (1957) that was directed by a former war correspondent who had covered the French Indochine war. And then there were oddities such as “The Quiet American” (1958), an American film based on British Graham Greene’s prophetic novel about U.S. foreign policy failure in pre-war Indochina, which foreshadowed the Vietnam War.

Hollywood goes to war

The initial wave of films from Hollywood about Vietnam took a predictable course of trying to follow in the tradition of the tried and true World War II films. So you get romantic melodramas with Vietnam as the exotic backdrop in films like “A Yank in Viet-Nam” (1964). A New York Times review of the film did note the novelty of the film actually being shot in Vietnam. It also highlighted this piece of dialogue from what’s described as a “grinning nationalist” character: “First came the Japanese, then came the French, and now the Communists. We've been fighting all our lives." It was too early for him to add and next the Americans but the foundation is set.

Coming early in the real war was “To The Shores of Hell” (1966), which was noteworthy for having Master Sgt. William V. Bierd as an actor and uncredited technical adviser to the film. The grittiness of the battle scenes was enhanced by access to archival military footage and help from the U.S. Marine Corps in shooting the fighting scenes.

And of course there needs to be mention of John Wayne’s patriotic war film “The Green Berets” (1968) and the Charleton Heston narrated propaganda film from the United States Information Agency, “Vietnam! Vietnam!” (shot in 1968 and released in 1971). Both of these films mimicked what had been done during World War II but without acknowledging the increased complexity and divisiveness of Vietnam. So while we can watch many old Hollywood World War II films without wincing too much at their datedness, this pair of Vietnam War films date badly but convey a particular perspective on the war that is good to remember.

The Vietnam War film

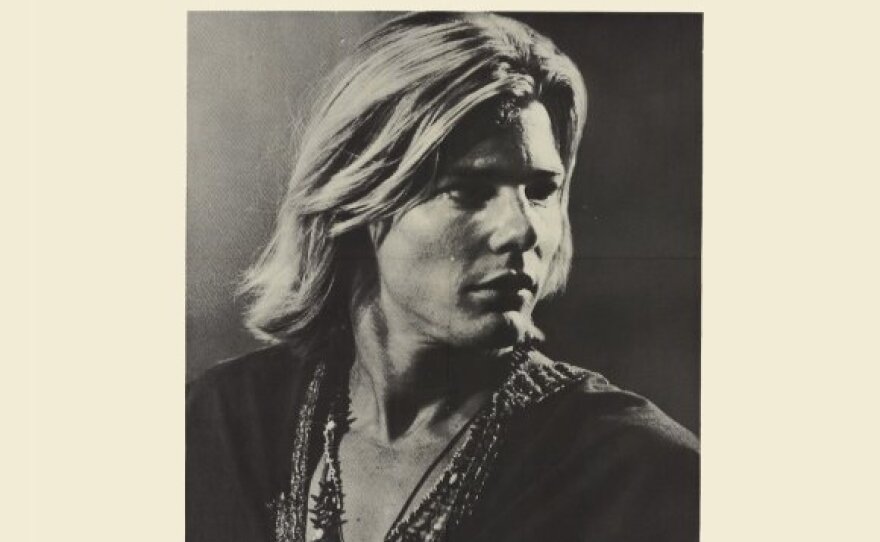

But the tone of films dealing with the Vietnam War soon changed and even within the mainstream of Hollywood. Network television surprisingly stepped up to the challenge producing one of the first looks at a returning war vet in “The Ballad of Andy Crocker” (1969), and then gave audiences a tough Marine drill sergeant (Darren McGavin) at odds with a hippie recruit (Jan-Michael Vincent) in “Tribes” (1970). “Tribes” gave equal weight to both sides in the debate but then felt the need to throw in a stereotypical villain in the guise of another drill instructor played with one-dimensional hostility by Earl Holliman. The screenplay by Tracy Keenan Wynn and Marvin Schwartz won an Emmy, and the film seriously and thoughtfully considered both sides of the war debate.

At this time there were also B movies like “Nam’s Angels” (1970, a.k.a. "The Losers") that just used the war as a topical hook for a ridiculous tale about Hell’s Angel style bikers recruited for mission in Cambodia.

Vietnam War vets were also likely to turn psycho in B movies such as Russ Meyer’s “Motorpsycho” (1965), and later in “Open Season” (1974) and “Combat Shock” (1986). There would also be the mindless action films Chuck Norris made popular and that would involve either covert operations in Southeast Asia or a war veteran on some sort of vigilante justice binge. Although not serious explorations of the war, they did reflect the very different ways people were processing the war and how society felt this particular group of vets were coming back changed in ways that had not been associated with previous generations of soldiers.

“Heroes” (1977) is recognized as first film released after the conflict ended in 1975 to genuinely address Vietnam War issues. Henry Winkler and Harrison Ford (in a film shot before he made “Star Wars”) star as returning Vietnam War veterans who are having trouble adjusting to life back at home.

The end of the war also triggered a number of films about fighting the war.

Perhaps because of the divisiveness of the war, filmmakers needed a little distance before tackling the war itself in depth. So following the end of the conflict audiences saw “Boys in Company C” (1977), “Go Tell the Spartans” (1978), “Hair” (1979 and based on the Broadway play), “A Rumor of War” (1980 TV movie based on Phil Caputo’s book), “Streamers” (1983), “The Killing Fields” (1984), “Platoon” (1986), “Full Metal Jacket” (1987), “Good Morning Vietnam” (1987), “Hamburger Hill” (1987), “The Hanoi Hilton” (1987 prisoner of war film), “84 Charlie Mopic” (1988 and one of the first “found footage” films), “Bat 21” (1988), “Gardens of Stone” (1987), “Casualties of War” (1989), “The Iron Triangle” (1989), “The Siege of Firebase Gloria” (1989), “Tigerland” (2000), and “Rescue Dawn” (2006 film that Werner Herzog based on his own 1997 documentary “Little Dieter Needs to Fly”) about a German-American pilot shot down in Vietnam).

Of these films, some gained acclaim like “Platoon” and “Full Metal Jacket” for showing a grunt’s eye view of the war while questioning the war or damning the absurdity of military aggression. A Washington Post film critic highlighted “Bat 21" as “a dove in hawk's plumage, an action-adventure that glorifies America's fighting men while it protests the war in Vietnam.”

“The Killing Fields” and “The Iron Triangle” were noteworthy for trying to convey a perspective from the other side. “The Killing Fields” looked to expose a Cambodian tragedy that was not widely reported while “The Iron Triangle” tried to humanize those on the other side of the DMZ. You can add to this Oliver Stone’s rather heavy-handed attempt to convey a Vietnamese perspective in “Heaven and Earth” (1993), which focuses on one woman’s experiences before, during, and after the war.

The returning vet

While many films were drawn to the dramatically more enticing tales of soldiers in the midst of combat or facing hardships as prisoners of war, other filmmakers chose to look at the soldiers returning home and trying to adjust to civilian life. Featuring less action and more emphasis on psychological drama, these films could be equally intense and provocative.

Elia Kazan’s “The Visitors” (1972) takes the true events (about soldiers killing a woman in Vietnam and being accused of a war crime) detailed in Daniel Lang’s book and Brian DePalma’s later film “Casualties of War,” and serves up a fictional account of what happened after the soldiers had returned home to civilian life. This film is often cited as the first to seriously deal with the struggles of the returning vet.

The theme got an odd but effective horror twist in Bob Clark’s “Deathdream” (a.k.a. “Dead of Night”) made in 1974 and one of the first to allude to soldiers dealing with PTSD. Although in this case, a young soldier returns from war literally a zombie. The horror genre provided the perfect canvas for a metaphor about the dehumanizing and soul-killing effects of war.

Films such as “Rolling Thunder” (1977), “Good Guys Wear Black” (1978), “First Blood” (1982, the film that introduced audiences to Sylvester Stallone as John Rambo), and “Missing in Action” (1984) used the returning vet as a protagonist whose war experience could provide him with special skills that could kick a revenge tale up a notch or with psychological baggage that could give an edge to a character or provide the catalyst for unleashing a violent rampage.

Perhaps the most thoughtful exploration of the returning vet theme can be found in Hal Ashby’s “Coming Home” (1978), which looked at a pair of disabled vets. Jon Voight’s character suffered a physical disability whereas Bruce Dern’s returning vet bore psychological scars. The film had a political ax to grind but did so with compassion more than rage. The presence of Jane Fonda, who was an outspoken anti-war activist during the Vietnam War, as one of the main characters brought the film added attention and prompted a broader discussion about the war.

Oliver Stone’s “Born on the 4th of July” (1989 and based on a true story) took a more heavy-handed and overtly political stance on the war from the perspective of a disabled vet returning home.

And then there’s ‘Apocalypse Now’

“Apocalypse Now” deserves a special mention because it is specifically about the Vietnam War and yet it’s also about so much more. At the Cannes Film Festival in 1979, where the film was unveiled, director Francis Ford Coppola made this statement at a press conference: “My film is not a movie. My film is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam. It’s what it was really like. It was crazy. And the way we made it was very much like the way the Americans were in Vietnam. We were in the jungle. There were too many of us. We had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little, we went insane.”

That kind of says it all, and the film conveys the absurdity and insanity of war in a manner unparalleled by any other film. It’s not that there aren’t better war films but “Apocalypse Now” is just larger than life and crazily surreal in a way that no other film has quite attained.

The film is an uncredited adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella, “Heart of Darkness,” with a script by John Milius, copious rewrites by Coppola and a voice over narration by Michael Herr (author of the Vietnam book “Dispatches”). Coppola moves Conrad’s story from the Belgian Congo of the 1890s to Vietnam in the 1960s.

The social turmoil and imperialistic endeavors of the late 1800s prompted Conrad to write his critique of society and allegory of man’s search for self-knowledge. His tale concludes its journey down the river with the discovery that man has a “heart of darkness.”

Coppola’s trip down the river leads to a similar conclusion and comparison of individual versus societal evil. But Coppola’s descent is also one through various level of insanity. There’s Willard’s depression as he waits for his mission; the absurdity of the war; the obsessive madness of the French who insist on staying on their plot of land till they die (this is only in the “Redux” version); the drugged-out haze of the young soldiers; Willard’s single-minded dedication to his mission and Kurtz’ insistence on taking everything to a logical extreme. What’s most striking about the film is how amazingly fresh and current it remains. The setting may be Vietnam but the discussion of ideas about war, American involvement in foreign countries, and the human capacity for evil are all still highly relevant.

Documentaries

If there are only two films you watch about Vietnam, I would suggest that they be a pair of documentaries: “Hearts and Minds” (1974) and “Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara ” (2003). These two films in conjunction with each other provide a fascinating and thought-provoking overview of the Vietnam War from pre-war to its aftermath.

“Hearts and Minds” was directed by Peter Davis, and took its title from a quote by President Lyndon B. Johnson: "the ultimate victory will depend on the hearts and minds of the people who actually live out there.” The movie, which polarized audiences and critics, was the surprising winner of the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature at the 47th Academy Awards presented in 1975. But it captured one side of the war debate while the country was still fighting the war, and it fueled debate.

Errol Morris’ documentary focused on the life and times of former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara and his observations of the nature of modern warfare, including Vietnam. The title is taken from the military concept of the "fog of war" depicting the difficulty of making decisions in the midst of conflict. As with “Hearts and Minds,” “Fog of War” an Academy Award for Best Documentary.

There are a number of other documentaries that provide a variety of perspectives on the war and the era: “The Anderson Platoon” (1967 from France), “A Face of War” (1968), “Street Scenes” (1970 anti-war documentary), “The World of Charlie Company” (1970), “Dear America: Letters Home From Vietnam” (1987), “Berkeley in the 60s” (1990), “Regret to Inform” (1998), “Daughter From Danang” (2002), “Enemy Image” (2005 from France), “Sir! No Sir!” (2006) about the anti-war movement within the military, and most recently “Last Days in Vietnam” (2014). There is also the oddity of Jean-Luc Godard’s cinematic essay “Letter to Jane,” in which he and Jean-Pierre Gorin dissect a photo of Jane Fonda in North Vietnam; her 1972 trip to North Vietnam during the war earned her the nickname of Hanoi Jane.

Not about the war, but about the war

Although “M*ASH” (1970) was set in the Korean War, it most definitely was a film about Vietnam. The doctors in “MASH” had a cause — they were against the war — and all their acts of rebellion, no matter how silly, were to point out the absurdity of war and the military. And despite their drinking, womanizing and lack of respect for authority, they were motivated by both morality and compassion when it came to valuing human life. Robert Altman used MASH to criticize the war and politics of the '70s.

“Easy Rider” (1969) is another film that overtly has nothing to do with Vietnam and yet is completely a result of the war. The film defined a new Hollywood independence and represented the rebellious counterculture. But neither of these might have manifested themselves in quite the same way without the war. The divisiveness that the film depicts between its hippie leads (Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda) and the conservative mainstream they encounter is a reflection of how the country was split. And the senseless death of these free-spirited characters echoes the feeling many had about the deaths of so many young Americans in the war.

I would also like to add a film that represents the flip side of this, Michael Cimino’s “The Deer Hunter” (1978), a film set against the backdrop of the Vietnam War but really has absolutely nothing to do with the war.

Cimino needed something to test his band of male friends and war was what he needed, and he chose the Vietnam War, although it could have been any war. So the frequent inclusion of “The Deer Hunter” on lists of Vietnam War films has always seemed odd and inappropriate to me. Many pointed out that the Russian Roulette device that provides a key metaphor in the story was something that was not documented as a part of what was happening in prisoner of war camps. But it was a device Cimino needed for his story. So there is not much that is specifically about Vietnam that is in the film and definitely nothing about that particular politics of that war so in that respect it doesn’t seem to merit a slot on the list of Vietnam War films.

Through foreign eyes

And finally, here are a few films to offer a radically different perspective, one rarely shown in the U.S. and these films are still hard to come by: “17th Parallel, Nights and Days” (1970, North Vietnam), “The Abandoned Field: Free Fire Zone” (“Cánh đồng hoang,” 1979, Vietnam), “Boat People” (1982, Hong Kong), and “Vu khuc con co” (“Dance of the Stork,” 2002, made Singapore as a co-production with North Vietnam and focusing on the North Vietnamese experience during the war). I also want to mention a pair of films that were co-productions between Vietnam and other countries: "Cyclo" (1995 with France and Hong Kong) and "Three Seasons" (1999 with the U.S.). “The Abandoned Field: Free Fire Zone” is a drama film directed by Nguyễn Hồng Sến and which won the Golden Prize and the Prix FIPRESCI at the 12th Moscow International Film Festival. It provides a view from ground level of those below the American helicopters.

And while not a foreign film (it is considered a U.S. independent film), Ham Tran’s “Journey From the Fall” (2006) delivers a story about one Vietnamese family’s struggle to survive in the aftermath of the war. Ham Tran hopes that his film will provide a starting point for a broader discussion about the Vietnamese experience.

And in essence that’s what pop culture has the power to do. It offers us entertainment but it’s entertainment that resonates in unexpected ways and captures who we are at a particular moment in time in a manner that’s truthful, telling, and accessible. This list is by no means complete but it highlights the best and broadest spectrum of films dealing with the Vietnam War and its aftermath.