It takes awhile to get to the last free place in America. It's 140 miles east of San Diego where farmland turns to dusty towns, which turns to parched desert.

An abandoned guard post covered in graffiti tells us we’re close. There hasn’t been a guard here for more than 60 years. This used to be a Marine training base called Camp Dunlap. The military pulled out after World War II and left concrete slabs behind.

Behind The Story

On a recent weekend in March, KPBS sent three of its journalists — reporter Angela Carone, videographer Katie Schoolov and web producer Brooke Ruth — to the Imperial County outpost known as Slab City. They went to tell the story of the squatters living on state-owned land, and how their world could soon be upended.

Years later, those slabs drew snowbirds in RVs looking for a free place to park and stretch retirement dollars. They also inspired what would become the community’s name: Slab City.

Snowbirds still come to the Imperial County spot for the winter months, though the population is shrinking. The rest, roughly 200 people, call Slab City home year-round. Temperatures can be as high as 120 degrees in the summer.

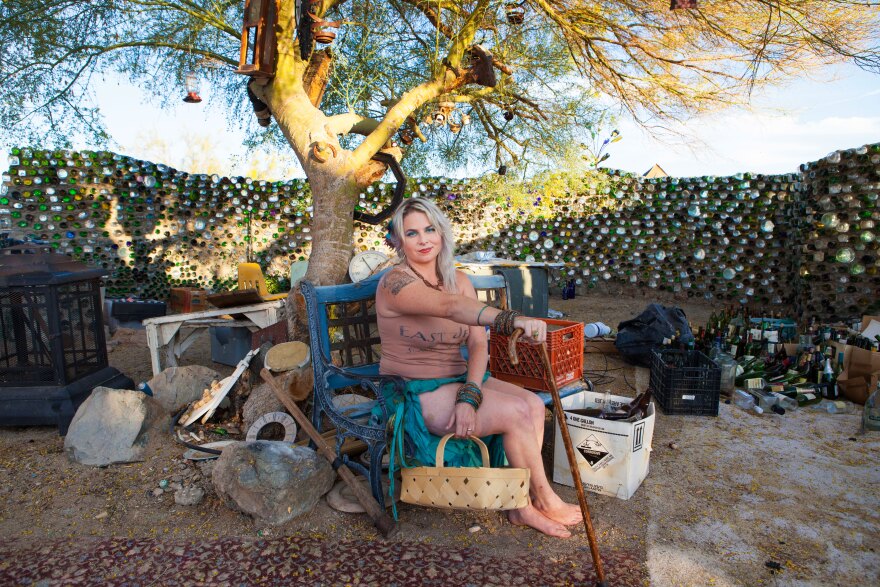

Some come to the Slabs to escape modern society. Many are destitute. Others just don’t want to be found. A few are fugitives or drug addicts. Others are young nomads. There’s even a population of modern day hobos — Slabbers call them “train kids” — who come through on a regular basis.

People have lived on Slab City’s 640 acres for decades. They are squatters on state-owned land. They don’t pay rent, and so it’s often referred to as “the last free place in America.”

But that freedom is getting more tenuous. The state is considering selling the land. Talk of the sale has spurred some residents to organize and take a leadership role. They’ve applied to buy the land. That frightens others who believe landlords, government and rules will follow, all of which run counter to how Slab City operates. They say it could destroy the “live and let live” philosophy of the Slabs.

Everyone who lives here wants to save Slab City. But can they preserve its freedoms in the fight to save it?

The end of the rope

There are no stop signs on Slab City’s dirt roads. Makeshift homes are made out of old school buses, broken down trailers or tents with added pallets and blankets for sturdiness. There are fancier RVs, too. Some have solar panels. There’s a church and a new library.

Every year, the residents do the unlikeliest thing. They throw a prom. They say they do it because so many of them didn’t attend their own proms.

When we visited, Bill Ammon was setting up for the big night. He goes by Builder Bill, a name leftover from the days when Slab City residents, or Slabbers, communicated by CB radio (other local handles on the CB were Toy Man, Rooster and Gold Man).

Builder Bill runs The Range, Slab City’s outdoor music venue. There’s a stage between two buses. Torn couches and ratty chairs provide the seating under strings of café lights. Builder Bill’s wife, Robin, has been gathering prom dresses from thrift stores for people to borrow.

Builder Bill was working construction in San Diego 16 years ago. Jobs dried up and soon he was living out of a van. He got tired of the police telling him to “move on.”

He heard rumors about Slab City. “When it’s time to get out of Dodge, you have to go somewhere right?” Builder Bill said.

He calls this desert community the end of the rope.

“You know you can retreat, retreat and retreat, and there’s one last little knot on the end of the rope,” he said. “That’s Slab City.”

Builder Bill said the Slabs are also freedom: freedom from rent, freedom from zoning laws and freedom from harassment.

“At Slab City you can just sit down and occupy a spot on the planet without any indebtedness or persecution,” he said.

But freedom has a price. There’s no electricity here. No water. No sewer system.

It may be free, but it’s also free from garbage pickup. The land is covered in trash.

“It’s just a piece of useless, unwanted, unusable desert,” Builder Bill said. “And that’s why we’ve been allowed to be here all of these years, because they didn’t have to look at us.”

The state of California has tried to sell the land in the past without luck. No one knows how much it would cost to clean it up.

Munitions and military waste could be buried on the land. The federal government is looking into that now.

The state is open to selling the land again. The nonprofit group that oversees Salvation Mountain, a nearby artwork and tourist draw, is applying to buy the land the mountain sits on. The East Jesus Art Collective, which operates an artist residency and sculpture garden at the edge of Slab City, has applied to buy that land, which would leave close to 500 acres of Slab City up for grabs.

And for the first time, Slab City residents are applying to buy it.

“I got to thinking, if the state is getting ready to unhorse this land, we all depend on this place,” Builder Bill said. “I thought we better do something.”

If not us, who?

Builder Bill helped form the Slab City Community Group. The members made it a nonprofit community land trust in 2014, complete with bylaws and a board of directors. Community land trusts are nonprofits that serve as stewards for affordable housing and other assets on behalf of a community.

Slab resident and board member Lynne Bright put together the application to buy the land.

Bright is a former attorney from Canada who has lived in the Slabs for more than six years. Her late husband, Mike Bright, was a longtime resident and Builder Bill’s sparring partner at Scrabble. We talked under a sprawling Palo Verde tree in front of her trailers. Bees hummed overhead. Her husband’s favorite recliner sat empty in a corner. He died just over a year ago of cancer.

Bright said they need to preserve Slab City from outside development and the encroachment of “the beast,” a term some Slabbers use to describe the world outside their community.

“If we do nothing and don’t organize, then who is the head that’s going to pop up and say, 'Wait a minute, not here?'” Bright said. “Who is going to do that?”

It’s not clear who would want to buy and develop this land. Slab residents have many theories.

“Solar energy, geothermal energy, wind energy, this whole valley is open to that,” Bright said.

The state said that’s unlikely, but the mere threat of a sale has shifted the thinking in this community. And that has some residents concerned.

Fear of having a landlord

Gary Brown came to Slab City seven years ago. He was an IT consultant who took a sabbatical. When he tried to re-enter the industry in 2008, at age 56, it was tough.

“Who wants to hire an ugly old man when you can get a kid from Mumbai for 25 bucks?” Brown said.

Brown’s RV has solar panels. He devised a way to live more comfortably through the summers by building an insulated room inside it. He can control the temperature inside. He calls it the cool cube. It’s big enough for a small desk and his computer.

Brown is adamantly against Slab residents organizing to purchase the land. He said that would bring the one thing Slabbers fear most: a landlord.

“If this place has to submit to building codes, the Slabs go away,” Brown said.

He wants the Slabs to be there for people who hit rock bottom — including those fighting mental illness.

“So that the really crazy people can at least live and fit in. And I think that’s important,” Brown said. “It went a long way in slaying my demons.

“There are a bunch of like-minded souls around here, scratching out an existence. This place needs to continue so they have somewhere to go.”

Bright said those who want to buy Slab City have no intention of charging rent. She also believes it’s time for the residents to have some control over their future. It was her husband and Builder Bill who came up with the tag line, “the last free place in America.”

“We’re going to have to help in a positive way in terms of cleanup,” Bright said. “And we’re going to have to engage with different levels of government.

"We’re going to have to grow up. And still maintain, somehow, the last free place in America.”

Prom night

At the Slab City prom, no one is thinking about land sales.

There’s a new prom king and queen. And a Sears-like photo booth with a paper moon and trellis of plastic flowers. Some people bring their dogs in the booth for a photo.

Various bands play. A woman in green body paint and a fox mask balances a hula hoop on her hips. The night is about celebrating the best of Slab City, where everyone is free to be whatever they want.

It will be months before the state decides whether to sell the Slabbers the land.

This poor community, where many residents live on Social Security or government assistance, will have to raise the money to buy it, which could cost as much as $500,000, according to the State Lands Commission.

Some residents insist state officials told them the land could sell for as low as $1 an acre. Even so, Slab residents haven’t been able to come up with the $5,000 application deposit.

At this point, the future of Slab City is uncertain. The homegrown effort to preserve Slab City’s way of life may mean compromising the very thing they are fighting for: freedom.