By the dawn of the 19th century, the most deadly killer in human history, tuberculosis, had killed one in seven of all the people who had ever lived.

The disease struck America with a vengeance, ravaging communities and touching the lives of almost every family. The battle against the deadly bacteria had a profound and lasting impact on the country. It shaped medical and scientific pursuits, social habits, economic development, western expansion, and government policy.

Film Quote

“The film also offers powerful lessons for us now, as we face deadly new contagions in our midst,” says AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Executive Producer Mark Samels. “Once again, a fearful populace and our public health authorities are grappling with how to respect the rights and dignity of the sick while doing everything possible to prevent the spread of illness and keep us safe.”

Yet both the disease and its impact are poorly understood: in the words of one writer, tuberculosis is our “forgotten plague.” Written, produced, and directed by Chana Gazit, "The Forgotten Plague" premiered on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE in 2015.

During most of the 19th century, consumption, as tuberculosis was then called, was believed to be hereditary. Rich, poor, young, or old, the disease struck indiscriminately and death could be sudden or painfully prolonged. Still, it was thought that a person’s environment could have an impact on the course of the illness and consumptives were advised to seek out fresh air and exercise in remote pristine environments.

Jumping on this growing interest in the “climate cure,” developers launched a massive advertising campaign aimed at luring health seekers to the newly opened territories of the West. Thousands of people with tuberculosis picked up and moved, bound for newly created towns such as Albuquerque, Colorado Springs, and Pasadena, where they formed the backbone of many new communities.

The realization that the disease was contagious came in 1882, when the tuberculosis bacillus was discovered.

It would take another decade before the medical community was convinced that a simple bacterium caused tuberculosis. As Americans came to better understand the disease, attitudes toward tuberculosis sufferers changed dramatically. No longer welcomed among the healthy, they were isolated in sanatoriums for their own health and to prevent the spread of the contagion.

Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, whose daughter had died from TB and was a sufferer himself, established the country’s first sanatorium at Saranac Lake, New York in 1884. Trudeau insisted on a strict regimen of fresh air—patients sat out in the cold for hours on porches in newly designed “Adirondack chairs” that were soon adopted by sanatoriums across the country. Although many patients benefitted from the isolation, others faced powerful loneliness and felt they had been banished against their will.

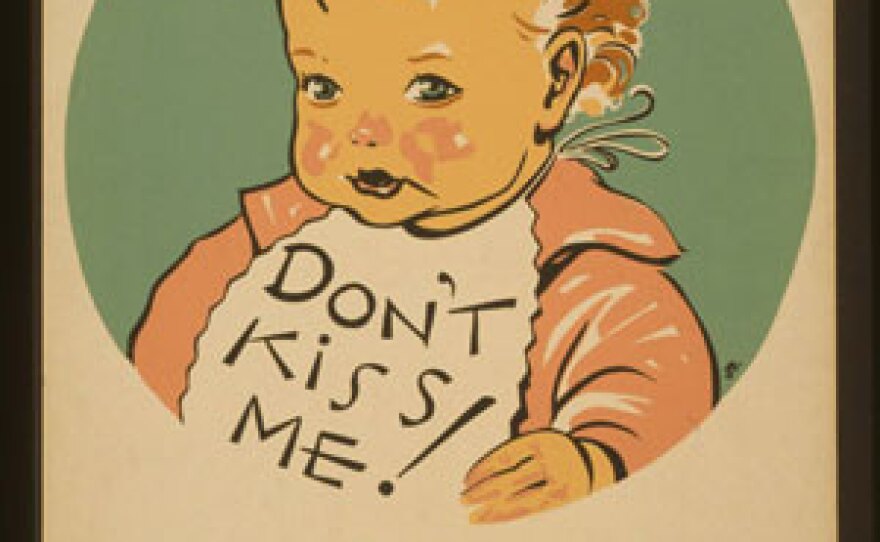

As Americans struggled to combat the contagion, social customs reflected the new fear of germs. Women’s hemlines rose to avoid contact with dangerous particles and men shaved their beards. And while improved hygiene started bringing the overall rate of tuberculosis down, in poor, crowded neighborhoods the numbers continued to rise. By the early decades of the 20th century, immigrants were twice as likely to die of the disease and the death rate for African Americans was three to four times higher. Public health officials launched an unprecedented campaign to improve the lives of the poor: better housing and working conditions, reduced working hours, and child labor laws.

Yet the anti-TB campaign also gave government officials unprecedented power to police the sick.

Health inspectors were free to monitor people’s movements, inspect their homes, and even commit people to public institutions against their will. The war against tuberculosis raised a profound question: how should Americans balance the need to protect their communities from a highly contagious disease with the need to protect the rights of the sick to be treated with dignity and compassion?

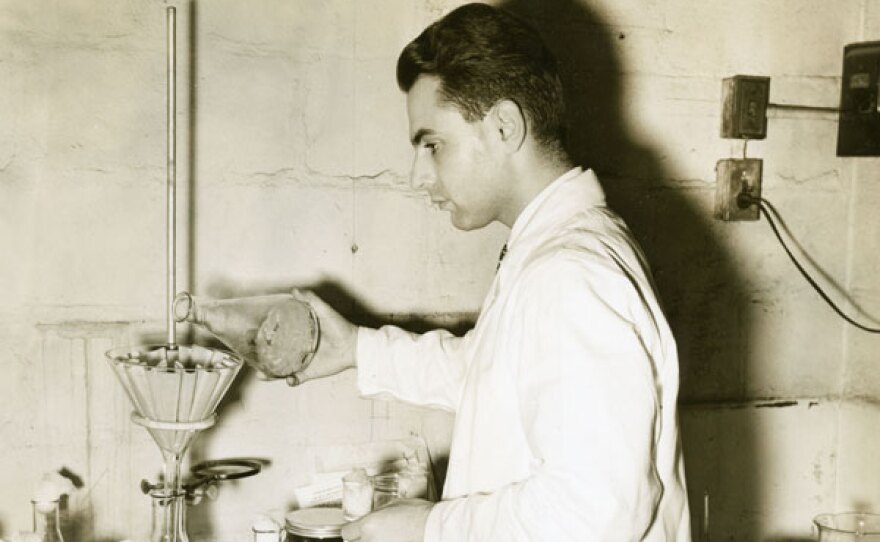

In 1943, Albert Schatz, a young microbiologist at Rutgers University working under a pioneering scientist named Selman Waksman, discovered streptomycin, an antibiotic that seemed to be a miracle cure for tuberculosis.

Within two years of its first use, streptomycin proved to be a breakthrough treatment and liberated many patients from the sanatorium. But the tuberculosis bacterium was a powerful adversary, mutating into strains resistant to the drug. Eventually, combining streptomycin with other antibiotics proved more effective.

For decades, deaths from tuberculosis in the U.S. declined to the point where it seemed the disease would be eradicated. In the 1980s, it suddenly reappeared alongside the AIDS epidemic. The disease that had stalked the nation for centuries—and continues to kill millions worldwide each year—stubbornly refuses to die.

Told through the remembrances of those who lived—and were cured—at the sanatoriums, along with historians and scientists, "The Forgotten Plague" is a powerful reminder of the centuries when American families lived under the constant shadow of a terrible death.

Past episodes are available for online viewing. AMERICAN EXPERIENCE is on Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr, and you can follow @AmExperiencePBS on Twitter.

The Forgotten Plague Preview

"By the dawn of the 19th century tuberculosis had killed one in seven of all the people who had ever lived. The battle against the deadly bacteria had a profound and lasting impact on the US