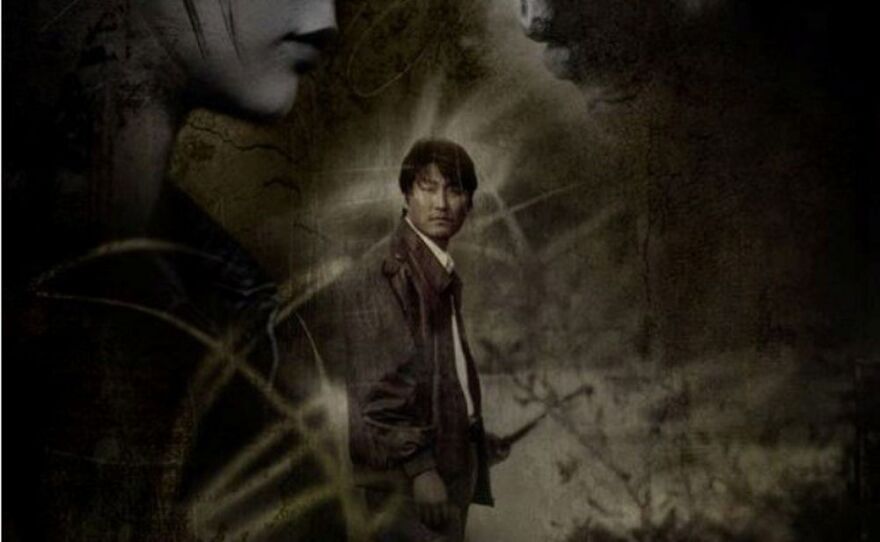

ANCHOR INTRO: Acclaimed South Korean director Park Chan-Wook makes his U.S. debut this month with the film “Stoker.” KPBS arts reporter Beth Accomando says San Diego audiences should prepare by checking out the Park Chan-wook retrospective this weekend at Reading’s Town Square Cinemas. ========================== The films of South Korean director Park Chan-Wook’s films may send some fleeing for the exit because he often and unapologetically puts you through the grinder. CLIP fight scene SFX He's not interested in feel good films. Instead he consider a world where good intentions go awry, decent people do bad things, and fate deals cruel cards. He’s most famous for his revenge trilogy – “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance,” “Oldboy,” and “Lady Vengeance.” “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” is the most mature, controlled and emotionally resonant of the three. The revenge here is ironically fueled by good intentions gone horribly wrong. The audacious “Oldboy” gives us a protagonist who attains tragic stature, like a shaggy King Lear undone by his own foolishness. Then the final chapter, Lady Vengeance, suggests hell hath no fury like a woman bent on revenge. The films move from the impossibility of salvation in “Mr. Vengeance” to the religious iconography and hope of redemption in “Lady Vengeance.” CLIP religious music Park doesn’t provides conventional heroes or villains, just frustratingly complex human beings. But even at their darkest, his films find surprising and heartbreaking shreds of humanity. They also dazzle us with ferocious, provocative artistry. Beth Accomando, KPBS News.

“Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” (playing as part of the Park Chan Wook Retrospective on March 9 at 4:00pm at Reading’s Town Square Cinemas) was the first of Park Chan-wook’s Revenge Trilogy yet it arrived in the U.S. after Park’s "Oldboy," which is the second installment. But it doesn’t matter what order you see these devastating films in, just see them, and you'll have a chance to catch all three this weekend.

Director Park Chan-wook exploded on the South Korean screen in 2000 with “Joint Security Area (JSA),” a taut thriller involving North and South Korean guards in the DMZ. Along with Kang Je-Gyu (“Shiri”), Park helped usher in South Korea’s era of homegrown box office blockbusters. After “JSA’s” success, Park had carte blanche to make whatever he wanted. But rather than follow up with a sure-fire commercial venture, he opted for a idea he’d conceived in the mid-1990s—a dark, disturbing tale about a young girl’s kidnapping and her father’s quest for revenge. “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” became the first of Park’s Revenge Trilogy. The second is “Oldboy,” and the final chapter, “Sympathy for Lady Vengeance,” has just been released in South Korea. Each film stands completely on its own but you don’t want to miss any of them because they do play off each other in creative ways.

“Oldboy” served up an audacious tale of revenge in which the protagonist attains tragic stature, like some shaggy King Lear undone by his own foolishness. “Sympathy” serves up a different kind of revenge tale, one that proves to be emotionally more complex. In part, “Sympathy” is a story of good intentions gone wrong. Ryu (Ha-Kyun Shin) is a deaf mute who reads lips. He sports green hair and the innocent face of a silent movie clown. He works at the local factory and takes care of his beloved but very ill sister (Ji-Eun Lim). She’s in desperate need of a kidney transplant but the doctor suggests that there’s little hope of getting one quickly. So Ryu decides to take matters into his own hands. He hooks up with some illicit organ dealers who promise that they will provide his sister with a kidney that matches her blood type. But they double cross Ryu.

Ryu’s militant girlfriend Cha Yeong-mi (Du-na Bae) suggests a kidnapping to get money for his sister's operation. Nab the daughter of a rich executive and hope he pays up quickly and quietly. And either way they will just let the kid go. Ryu doesn’t like the idea but a combination of desperation and Cha’s convincing argument that it’s a foolproof scheme prompt him to take action. Plus, they don’t have to be mean to the kid, they can just pretend they’re friends and the little girl has just come over to play.

Their victim is Yu-sun (Bo-bae Han) the young daughter of Park Dong-jin (Kang-ho Song of “JSA” and “Shiri”). Ryu’s sister finds out that Ryu has lost his job at the factory and has been hiding things from her. Her response sets off a series of tragic events and prompts a complex cycle of revenge that involves just about everyone but not always in the way you’d expect.

Park lets the rage and pent up frustrations of his characters explode into horrific violence. The ferocious brutality links the film to Asian Extreme Cinema, yet the richly textured emotions lift it to the level of Greek tragedy with an overwhelming sadness arising from the ironic fact that these characters are all motivated to violence by a compassionate love for someone else. Ryu loves his sister and would do anything to save her life; Park adores his daughter and would do anything to punish her kidnappers; and Cha cares deeply for Ryu and would do anything to protect him. Writer-director Park then places these characters of deep devotion in a violent, brutal world.

“Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” is by far Park’s most mature, controlled and emotionally resonant work. It begins slowly, mixing black humor with ever-increasing tension. The trick Park pulls off is that he makes us care for all the characters. But our sympathies constantly slip and slide as characters that we grow fond of behave in shocking ways. There are no conventional heroes and villains here, just frustratingly complex human beings who seem victims of both fate and their own follies. A recent flurry of South Korean films —“Sympathy,” “Oldboy,” “Save the Green Planet,” “A Bittersweet Life,” “Tae Guk Gi” — are fueled by an epic sense of sadness that seems to reflect Korea’s own violent history as it struggles with old wounds and newfound freedoms. The violence and the storylines of these South Korean films differ from other examples of the Asian extreme genre. In Hong Kong, the cramped, fast-paced cosmopolitan lifestyle produces over-the-top action that has less emotional resonance and more intoxicating, pop arty thrills. In Japan, the violent excesses play out more as a rebellious reaction to that country’s perceived formalism and tradition. But a number of Korean films display a sense of division, of torn emotions and aching sadness that seems in some way influenced by the fact that it is a country divided, with family members sometimes ending up on opposite sides of the border.

With “Sympathy,” Park once again dazzles us with his cinematic craft. Every scene, every frame reveals meticulous control and design. Take one brilliantly conceived and executed shot. The shot begins in the room next to Ryu’s apartment as four young men masturbate to what they think are the sounds of a woman at the height of sexual pleasure. But as the camera tracks through their apartment into that of Ryu’s, we see Ryu’s sister writhing on the floor in agony and desperately trying to get the attention of her deaf brother who is happily eating dinner with his back to her and oblivious to her pain. In this single shot, Park finds dark humor and sad irony in the jarring way these characters all occupy the same cinematic space.

Park also does a stunning job of showing how Ryu’s deafness isolates him from the world. Park drops the sound out at unexpected moments so we can experience the world as Ryu does and feel how cut off he can be. The silence, though, can also be comforting and an escape. Ryu’s inability to hear provokes one tragedy, and his inability to speak makes him a sadly silent victim of revenge. Park also uses sound creatively in the hearing world as well. At a funeral, the hysterically weeping mourners are silent behind a pane of glass whereas the sounds of an off screen autopsy — flesh cut open, a rib cage pulled apart — punctuate the agony of a surviving family member as he watches a coroner work.

Yet amidst all the pain and suffering, Park finds the most surprisingly tender moments. A ghostly visitation allows for one last embrace for one of the grief-stricken characters. Later, another character says goodbye to a friend by gently holding hands with the corpse in an elevator as the police transport the body downstairs. These quiet, gentle scenes offer a contrast to Park’s “Oldboy,” which was marked Park’s diabolical manipulation of both his character and the audience.

As with Park’s “Oldboy,” “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” (rated R for violence and sexual content and in Korean with English subtitles) may send some fleeing for the exit. Park puts you through the grinder. He’s not interested in making a film that doesn’t provoke a strong response. Viewers aren’t likely to exit “Sympathy” and casually consider where they should go for a bite to eat. Park forces us to consider a world where good intentions go awry, decent people do bad things, and fate deals cruel cards. But even at its darkest moments, “Sympathy” finds surprising and heartbreaking shreds of humanity. Park takes us someplace dark—he provokes us, rivets us to the screen, and disturbs us with his masterful manipulation of our emotions. He’s a filmmaker of ferocious talent and rare artistry, and he simply cannot be ignored.

I will be hosting a retrospective of all three of the vengeance films this weekend in anticipation of the release of Park's first U.S. film, "Stoker" on March 15.