Stream now with KPBS Passport on KPBS+ / Watch Saturdays, Dec. 6 and 13, 2025 at Noon on KPBS 2

LEONARDO da VINCI, a new, two-part, four-hour documentary directed by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon explores the life and work of the 15th century polymath Leonardo da Vinci, is Burns’s first non-American subject. It also marks a significant change in the team’s filmmaking style, which includes using split screens with images, video and sound from different periods to further contextualize Leonardo’s art and scientific explorations.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Inventions: Interactive 3D Model Explorations

LEONARDO DA VINCI looks at how the artist influenced and inspired future generations, and it finds in his soaring imagination and profound intellect the foundation for a conversation we are still having today: what is our relationship with nature and what does it mean to be human.

The musician and composer Caroline Shaw recorded original music for the film performed by Attacca Quartet, Sō Percussion and Roomful of Teeth. The voice of Leonardo is read by the Italian actor Adriano Giannini. Keith David serves as the film’s narrator.

Set against the rich and dynamic backdrop of Renaissance Italy, at a time of skepticism and freethinking, regional war and religious upheaval, LEONARDO DA VINCI brings the artist’s towering achievements to life through his prolific personal notebooks, primary and secondary accounts of his life, and on-camera interviews with modern scholars, artists, engineers, inventors, and admirers.

The film weaves together an international group of experts, as well as others influenced by Leonardo who continue to find a connection between his artistic and scientific explorations and life today. As the filmmaker and Leonardo admirer Guillermo del Toro says at the beginning of the film, “the modernity of Leonardo is that he understands that knowledge and imagination are intimately related.”

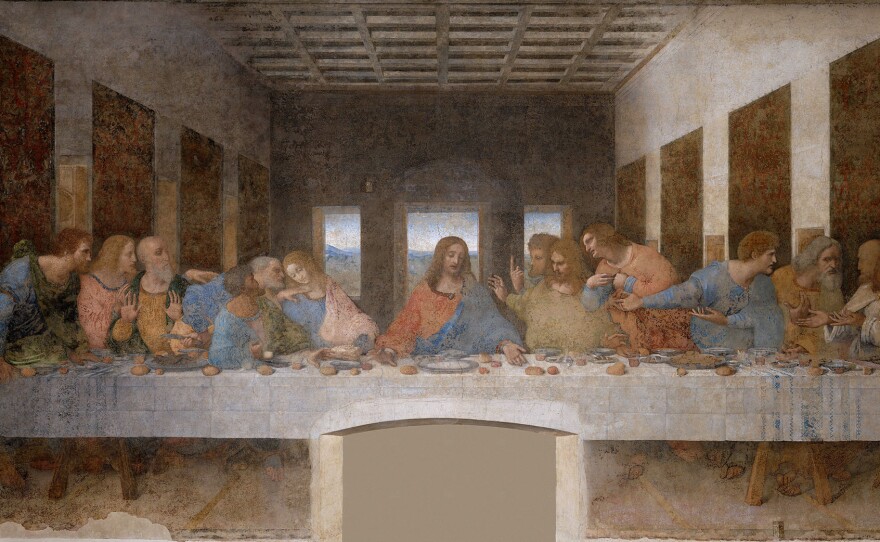

Born out of wedlock to a notary and a peasant woman, Leonardo distinguished himself as an apprentice to a leading Florentine painter and later served as a military architect, cartographer, sculptor, and muralist for hire. His paintings and drawings, such as the "Mona Lisa," "The Last Supper," and the "Vitruvian Man," are among the most celebrated works of all time and his art was often equaled by his pursuits in science and engineering.

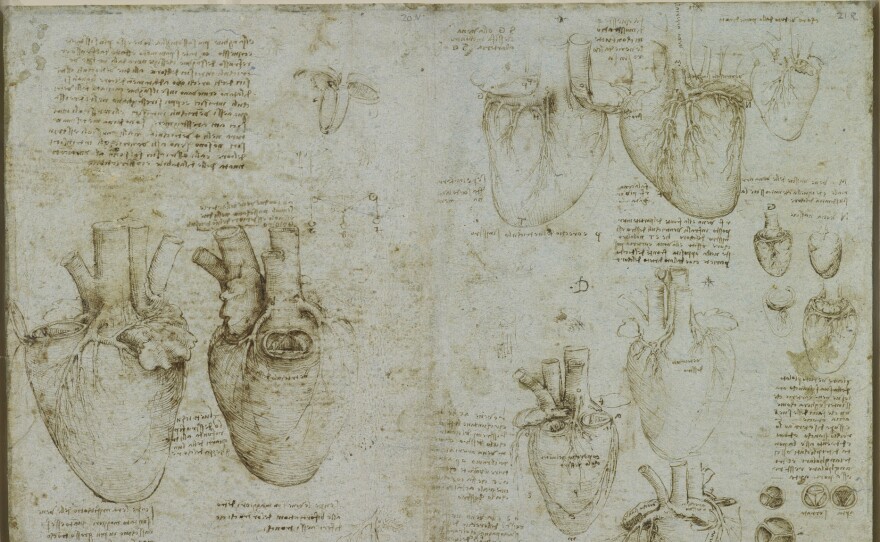

LEONARDO da VINCI follows the artist’s evolution as a draughtsman and painter, scientist and engineer, who used notebooks to explore an astonishing array of subjects including painting, philosophy, engineering, warfare, anatomy, and geography, among many others. Though he intended to publish his writings, he never did, but the film delves into those he left behind to get inside his mind as he strove to master the laws of nature and apply them to his endeavors.

Leonardo’s personal story is told within the larger context of the Italian Renaissance, a blossoming of art and architecture informed by mathematics and science, and an awareness of the natural world, but also steeped in a renewed interest in classical ideals.

In Part One, “The Disciple of Experience,” the film takes us into the world of the bottega, the studio or workshop where Leonardo apprenticed and learned how to prepare paints but would also have discussed math and poetry with his master – the artist Verrocchio – and fellow apprentices. By the age of 20 – in 1472 – he had joined a painter’s guild, whose members were among the most talented artists in Florence, including Filippino Lippi, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Pietro Perugino, and Sandro Botticelli.

Leonardo’s paintings and notebooks tell us much about how he saw the world, as well as the energy and passion he brought to trying to understand it. But we know surprisingly little about his inner life or what he thought about himself and others. Experts, including those in LEONARDO da VINCI, believe he was gay, but he wrote nothing about his sexuality, though homosexuality was for the most part tolerated in Florence at the time.

But we know a lot about how he perceived the outer world. For the dozens of figures who would populate an early unfinished painting – the "Adoration of the Magi" (1481) – he sat in the piazzas of Florence, observing and sketching. “You must wander around, and constantly, as you go, observe, note and consider the circumstances and behavior of men as they talk, quarrel, laugh or fight together,” he wrote. In the lower right corner of the unfinished painting, a young male figure, most likely Leonardo himself, gazes away from the dramatic center.

Leonardo would abandon that work, as he would many others. Another painting from that time – "Virgin of the Rocks" – depicts the Virgin Mary and her son, a common theme of Renaissance paintings. But unlike other paintings of the period, Leonardo’s Mary exudes a natural, maternal instinct, human and spiritual at the same time. “Absolutely the most complex Madonna image of the entire Renaissance,” the art historian Monsignor Timothy Verdon says. “Its complexity lies in a probing effort to understand a deep mystery.”

Leonardo worked on the painting in Milan and would soon win the patronage of Ludovico Sforza, the ruler of the Duchy of Milan. Leonardo would spend 18 years in the city and would produce some of his most famous works there. In a studio provided by his patron, he painted portraits, drew futuristic machines, and made observations in dozens of notebooks. The notebooks, which were written in a backwards script, so as not to smear the ink as he wrote with his left hand, provide us with key qualities of who he was. “It’s not just that Leonardo knew an awful lot,” says biographer Charles Nicholl, “It is that he found out an awful lot.”

Leonardo often sought wisdom from ancient philosophers and scientists, including Aristotle and Galen. He also found inspiration in a treatise by Vitruvius, a Roman architect, who wrote about the symmetry between the human body and a skillfully designed temple. The treatise led Leonardo to produce the drawing the "Vitruvian Man." As the Italian art historian Francesca Borgo explains in the film, “One of the most celebrated examples of a dialogue with ancient scholars, possibly even an attempt to surpass classical civilizations, is undoubtedly the 'Vitruvian Man,' one of the most famous drawings in Western art.”

Sforza would choose Leonardo in the early 1490s to prepare a mural for the dining hall of a monastery. He assigned the artist a suitable scene given the location, "The Last Supper." The painting, which still adorns the wall today, was his most ambitious to date – an opportunity for him to prove his ability as a painter. When finished, the mural rose to 15 feet in height and spanned 29 feet across the wall. It showcased Leonardo’s gift for blending tones and colors, his mastery of light and shadow and his command of geometry, which he wielded with great precision to bring harmony to a moment of chaos. Leonardo da Vinci had brilliantly rendered the gestures – both subtle and dramatic – that testified to the psychological states of his subjects.

In Part Two – “Painter-God” – Leonardo has left Milan and to travel to Venice and then back to Florence, the city where he had developed his artistic skills. It was there that Leonardo reached out to Cesare Borgia, the military strongman who led the Papal troops and was in search of an engineer and cartographer. He developed new ways to map cities and designed new technologies for invading and defending them.

Always fascinated with the movement of water, he also devised a way to divert the Arno, the river that flows west from Florence to Pisa and the sea beyond. The plan, which never came to fruition, would have denied Pisa, Florence’s long-time adversary, access to the river.

The brutal battlefield scenes he likely witnessed as a military engineer and cartographer for Borgia would also inform his art. Back in Florence, he was selected to produce a battle scene for the Council Room in the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of Florentine government. Many of the preparatory studies for the painting – "The Battle of Anghiari"– still exist, though Leonardo never completed the mural itself. The work would have been Leonardo’s largest.

In the following years, Leonardo would return to his observations of nature – with studies and sketches of water, of birds in flight (and flying machines), of horses and landscapes. He would also begin a portrait of the wife of the merchant Francesco del Giocondo, which would become his famed "Mona Lisa." The art historian Carmen Bambach explains that as Leonardo aged, he seemed to be increasingly focused on philosophy and the workings of the natural world and, once again, the human body, filling notebooks that would not be fully explored for centuries.

With access to cadavers for dissection, Leonardo depicted the blood vessels of neck, thorax and upper torso and the nerves and blood vessels of the head. He did similar studies of the abdominal organs – stomach, liver, bladder, and kidneys. He made notes on the colon and intestines, and what he believed was the heart’s importance in heating the blood. Francis Wells, a heart surgeon who has studied Leonardo’s writings and drawings, explains that he provided what amounts to the first description of coronary atherosclerosis.

Leonardo also explored science beyond the human body. “Gravity,” he wrote in one of his notebooks, “is limited to the elements of water and earth; but this force is unlimited, and it could be used to move infinite worlds if instruments could be made by which the force could be generated.” In one experiment, he used nothing more than a jar filled with sand to help him roughly calculate the earth’s gravitational constant. It would be a century before Galileo’s experiments proved gravity’s universal effect on objects and far longer before Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein would use calculus – not yet invented in Leonardo’s time – to define and explain gravity.

In 1516, now 64 years old, Leonardo received an invitation from the young King of France to move to Amboise, France, with the title Premier Painter and Engineer and Architect to the King. He relocated there with three of his unfinished paintings, "The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne," "Saint John the Baptist" and the "Mona Lisa." He would die there three years later, in 1519.

As the biographer Serge Bramly explains, at the end of his life “there’s a sense of disillusionment, he realizes that he won’t be able to see all of his projects through to the end… But just because a project is impossible to complete does not mean that it must be abandoned. On the contrary, that’s perhaps what gives it its greatness, its nobility.”

Watch On Your Schedule: LEONARDO da VINCI is now available to stream with KPBS Passport, a benefit for members supporting KPBS at $60 or more yearly, using your computer, smartphone, tablet, Roku, AppleTV, Amazon Fire or Chromecast. Learn how to activate your benefit now.

Credits: A production of Florentine Films and WETA Washington, D.C. Directed by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon. Written by David McMahon and Sarah Burns. Produced by Sarah Burns, David McMahon, Ken Burns and Tim McAleer. Edited by K.A. Miille and Woody Richman. Cinematography by Buddy Squires. Narrated by Keith David. The voice of Leonardo is read by the Italian actor Adriano Giannini. The musician and composer Caroline Shaw wrote and recorded original music for the film performed by Attacca Quartet, Sō Percussion and Roomful of Teeth. The executive in charge for WETA is John F. Wilson. Executive producer is Ken Burns.