Premieres Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024 at 8 p.m. on KPBS TV / PBS app + Encores Saturday, Oct. 5 at 7 a.m. and 1 p.m. on KPBS 2

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE “The American Vice President” explores the little-known story of the second-highest office in the land, tracing its evolution from a constitutional afterthought to its current position of enormous political consequence. Focusing on the fraught period between 1963 and 1974, when a grief-stricken and then scandal-plagued America was forced to clarify the role of the vice president, the film examines the passage and first uses of the 25th Amendment and offers a fresh and surprising perspective on succession in the executive branch.

“With the recent ascension of Vice President Harris to the top of the Democratic ticket and the increased media scrutiny over both parties’ VP picks, this film is more relevant than ever,” said Cameo George, executive producer of AMERICAN EXPERIENCE. “This is the perfect time for a look back at how — and why — the role of the vice presidency has transformed over the years.”

10 Surprising Facts About U.S. Vice Presidents

What happens when the President of the United States is unable to fulfill the duties of the office due to illness, incapacity or death? Incredibly, it is a question that went without a definitive answer for much of American history. The framers of the Constitution named the vice president the designated successor to the commander-in-chief but were vague about the myriad details that would necessarily attend such a transfer of power. More incredible still, despite the assassinations of three sitting presidents (Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley) and the deaths of four more in office (Harrison, Taylor, Harding, FDR), it wasn’t until 1963 that the ambiguity in the Constitution was finally deemed worthy of redress.

When Americans vote in a typical presidential election year, vice-presidential candidates are usually not top of mind. Given just two responsibilities by the Constitution—to stand in for the president and cast a tie-breaking vote in the Senate—the first V.P., John Adams, called his office “the most insignificant...that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.” Teddy Roosevelt, who was twenty-fifth, anticipated being able to attend law school during his term, so “functionless” was the role.

Nevertheless, from time to time, the matter of succession would become an urgent issue. Between 1841 and 1962, seven presidents died in office, and seven vice presidents ascended to the presidency. Numerous others hovered on the threshold of the Oval Office for weeks or months on end while the commander-in-chief languished within—convalescing from a wound, a stroke, a heart attack—and leaving the nation to wonder just who was in charge. In each case, concern over the murkiness in the Constitution would emerge, only to fade once the crisis had passed.

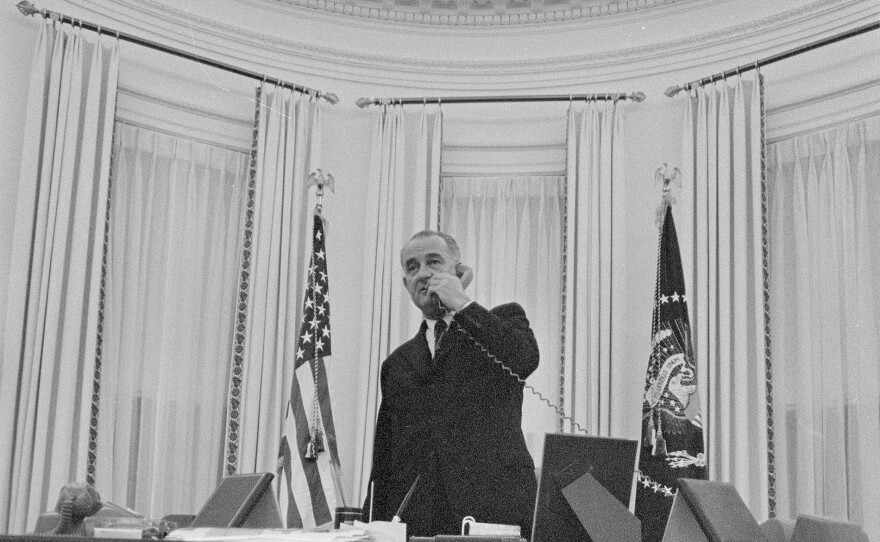

Then came the shocking death of President John F. Kennedy. Witnessed by millions on live television, Kennedy’s assassination threw the nation’s predicament into stark relief, as Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson became the eighth man to ascend to the presidency, and the vice presidency was left vacant with no constitutional mechanism to fill the office.

Amid the perils of the nuclear age, civil rights protests and a war brewing in Vietnam, the role of the vice president and the constitutional ambiguity around succession was now a matter of urgent national concern. Led by a freshman senator from Indiana named Birch Bayh, Congress spent the next 18 months debating a proposed constitutional amendment, the 25th, which ultimately provided detailed procedures for both a transfer of presidential power and a means of filling a vice-presidential vacancy.

Ratified in 1967 the 25th Amendment was invoked for the first time in 1973, under circumstances that no one involved in its drafting had likely ever imagined, when Vice President Spiro Agnew was forced from office under the cloud of a corruption scandal.

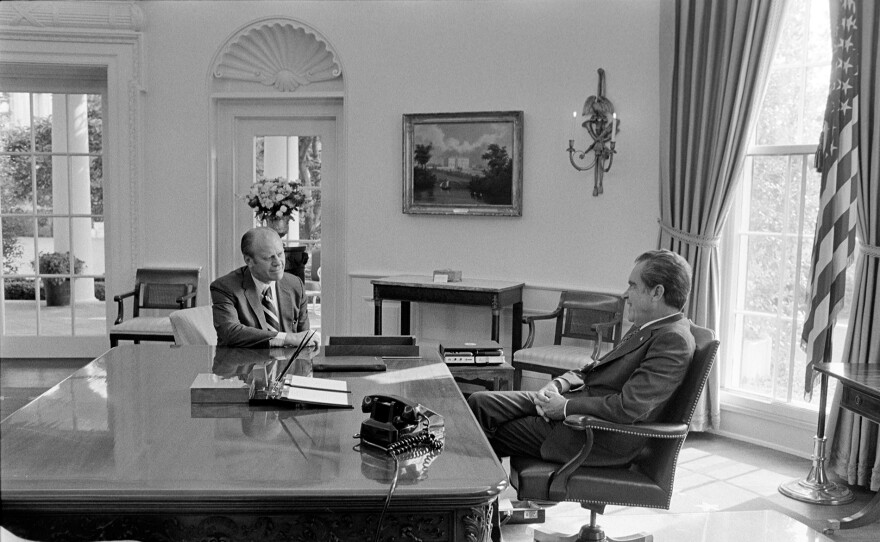

Empowered by the amendment to nominate a replacement—pending confirmation by a majority of both houses of Congress—President Richard Nixon named an obscure Michigan congressman, Gerald Ford, to the vice presidency.

Eight months later, Nixon himself was engulfed by the Watergate scandal and abruptly resigned, bringing the 25th Amendment into play once more. By the close of 1974, the highest elected offices in the land—the presidency and the vice presidency—were occupied by men who had not been elected to them. In the process, however, a new vision of the American vice president had begun to take hold: as a close partner to the president and an increasingly important figure in the executive branch.

RELATED: No one used to care about the vice presidency. Here's how (and why) that's changed

RELATED: Inside the Chaotic Early Days of Gerald Ford’s Presidency

About the Participants:

- Kate Andersen Brower is the author of “First in Line: Presidents, Vice Presidents, and the Pursuit of Power.”

- Jared Cohen is the author of “Accidental Presidents: Eight Men Who Changed America.”

- John D. Feerick was a member of the ABA panel involved with the passage of the 25th Amendment and is the author of “The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Its Complete History and Applications.”

- Joel K. Goldstein is the author of “The Modern American Vice Presidency: The Transformation of a Political Institution” and “The White House Vice Presidency: The Path to Significance, Mondale to Biden.”

- James E. Hite is author of “Second Best: The Rise of the American Vice Presidency.”

- Rachel Maddow is an MSNBC journalist, host of “Bag Man: The Podcast” and author of companion book “Bag Man: The Wild Crimes, Audacious Cover-up & Spectacular Downfall of a Brazen Crook in the White House,” about Vice President Spiro T. Agnew.

- Ramesh Ponnuru is editor of the National Review, a columnist for The Washington Post and senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Watch On Your Schedule: AMERICAN EXPERIENCE “The American Vice President” will stream for free simultaneously with broadcast on all station-branded PBS platforms, including PBS.org and the PBS app, available on iOS, Android, Roku, Apple TV, Amazon Fire TV, Android TV, Samsung Smart TV, Chromecast and VIZIO. The film will also be available for streaming with closed captioning in English and Spanish.

Credits: Produced, Written and Directed by Michelle Ferrari. Edited by Karl Dawson. AMERICAN EXPERIENCE is a production of GBH Boston. Executive Producer: Cameo George.