As theaters went dark and the world ground to a halt in 2020, filmmaker Noah Baumbach picked up a novel that spoke of a different apocalyptic tragedy. Baumbach hadn't read Don DeLillo's White Noise since it came out in 1985, when he was a teenager.

"It had a big effect on me at the time," Baumbach told NPR's Steven Inskeep about the film, now out in U.S. and U.K. theaters. "I kept stopping and reading it aloud to Greta (Gerwig, his partner) or to anybody who would listen and just saying, I can't believe how much this book speaks really to all time... then it coincided with the pandemic. And that's really when I thought, well, maybe I'll try to see if there's a movie here."

Baumbach's eponymous film, like DeLillo's novel, is a highly stylized, preposterous satire of consumerism and mass media that also manages to parody academia, reflect on family life ("the cradle of misinformation") and middle age, and wrap it all in an extravagant disaster plot.

"I kept turning on the TV news and seeing toxic spills and it occurred to me that people regard these events not as events in the real world, but as television — pure television," DeLillo himself told NPR at the time that White Noise was published. The novel won the U.S. National Book Award for Fiction.

In the film, the supermarket doubles as a kind of candy-colored temple. Don Cheadle's character, Professor Murray Siskind, extols its merits as a "gateway" between death and spiritual rebirth.

"Look how bright. Look how full of psychic data, waves and radiation. All the letters and numbers are here, all the colors of the spectrum, all the voices and sounds, all the code words and ceremonial phrases," he says. "You just have to know how to decipher it."

Jack Gladney (played by Adam Driver), the head of the Hitler studies department at a small liberal arts college, narrates the film. Gladney is also behind the very concept of Hitler studies. He lives a comfortable life in a Midwestern suburb with his fourth wife, Babette (played by Gerwig) and four children from their collective six previous marriages. That comfort is upended by a menacing cloud — or airborne toxic event, as it's called in the film.

With its $100 million budget, White Noise is the most ambitious project to date for Baumbach, whose breakout film was The Squid and the Whale (2005) and whose last film was the critically acclaimed Marriage Story (2019).

Baumbach describes the movie, shot on film, as a "period piece." The costumes and cars very much belong to the 1980s and it features a complex car chase (with a flying family station wagon) and a fully staged train crash.

"It was a rig but it was pulled into the train and timed out and everything. We did a lot of the detail work separately of the canisters hitting each other," Baumbach said. "It does have a lot of visual effects in it as well, but they're designed to work with the same aesthetic."

Baumbach describes the eeriness that permeates his film as "this sort of otherness, this other reality that's like floating above the ground" — in short, the same sort of strangeness that accompanied pandemic era lockdowns.

"We all recognize when we have those times in our lives, you know, when we we we acknowledge that the world feels very strange to us. It's like things are familiar and not familiar," Baumbach said.

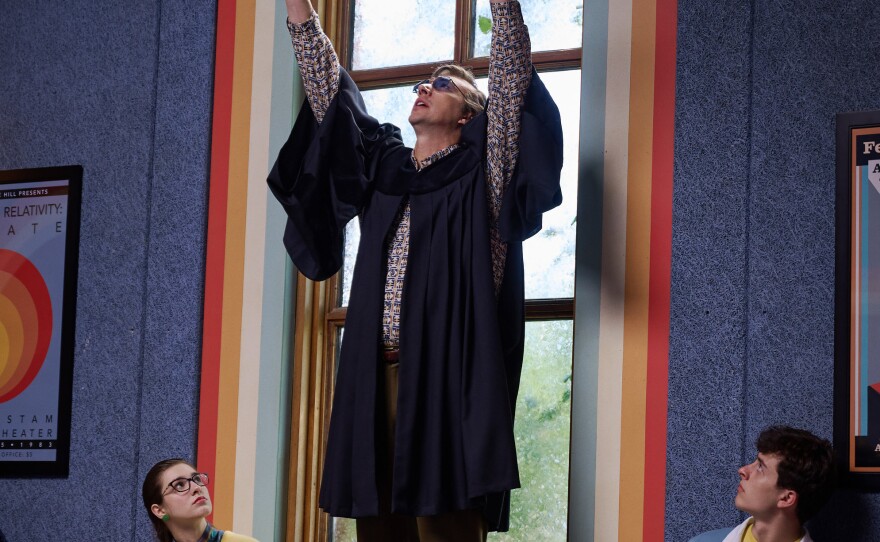

In one scene, Gladney gives a lecture on the crowds that listened to Hitler, and in the process inadvertently reveals his preoccupation with death.

"To become a crowd is to keep out death. To break off from the crowd is to risk death as an individual, to face dying alone," he tells assembled students and professors, his black cape spread out like some bird of doom. The scene is superimposed with images of the crash between a tractor-trailer carrying toxic waste and a train, which triggers the catastrophe.

Throughout the story there are competing narratives for what is or isn't "the truth." The Gladneys constantly speaking over one another combines with the incessant drone of the television and radio to create a cacophony of sound that sometimes becomes a symphony.

"That was even my direction to the kids. I said, you're like a radio that was turned down at the beginning of the movie and then you're just on for the whole time. So even even when you're off camera, just imagine you're still having this conversation," Baumbach said. "I saw the family in this movie as a kind of microcosm of the culture at large, which is how we both contribute to and also collaborate in false information. This story opens it up to the culture at large, this notion of fake news that we've been living with for the last few years."

This interview was conducted by Steve Inskeep and produced by Lisa Weiner and Shelby Hawkins.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))