In the 1840s, Elizabeth Blackwell was admitted to a U.S. medical school — in part because the male students thought her application was part of an elaborate prank. She persisted and got her degree, becoming the first American woman to do so. A few years later, her younger sister Emily followed in her footsteps, earning her own medical degree from the institution that would become Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

Biographer Janice Nimura tells the sisters' story in the new book, The Doctors Blackwell. Nimura says Elizabeth was "greeted with everything from rejection to hilarity" during her years at Geneva Medical College in upstate New York.

"There was the basic idea that a woman's sphere did not include anything professional," Nimura says. "The townspeople [of Geneva] basically thought that any woman who wanted to study medicine was either wicked or insane."

Nimura notes that even after graduation, the Blackwell sisters struggled to find patients. "The idea of a female physician — the very phrase 'female physician' — connoted an abortionist — someone who worked in the shadows, on the wrong side of the law," she says.

Elizabeth's career tended to focus on public health and education, while Emily was a more active medical practitioner, functioning as both a surgeon and an obstetrician. In 1857, the sisters helped established the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. Twelve years later, in 1869, they established the Women's Medical College in New York City.

Today, both women are regarded as feminist trailblazers, but Nimura notes that they were also "complicated, prickly, sometimes self-contradictory people." Elizabeth, for instance, regarded the women of her day as trifling gossips and took a dim view of the women's suffrage movement.

"To me, that taught me that it's really important in this moment to kind of relearn how to admire women," Nimura says. "To understand that a heroine doesn't always have to be a Disney princess, but can be a woman with all sorts of rough edges and complications and that we can admire them profoundly anyway."

Interview highlights

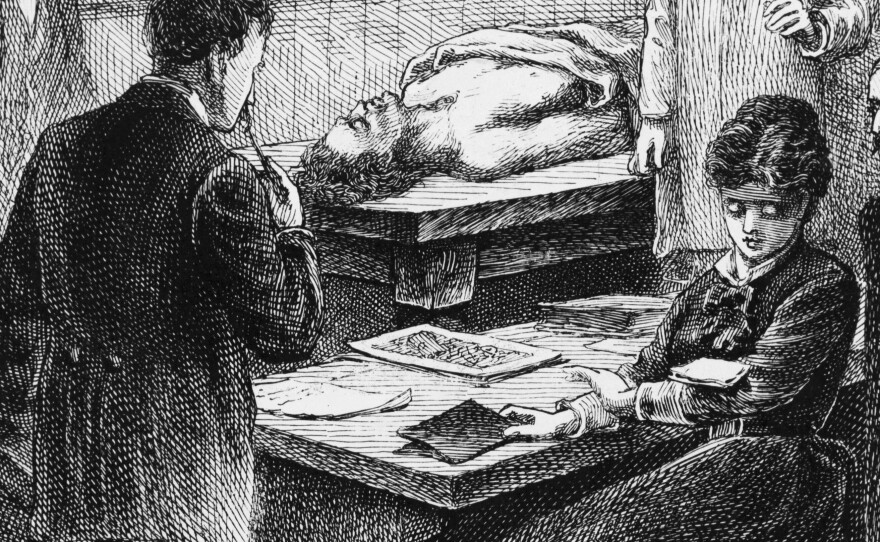

On the reasons that were given for excluding women from becoming doctors

There was the idea that if you let a woman go to medical school, she's going to be sitting in a lecture hall alongside men talking about the human body, and that's not proper. That's appalling. Especially when you get to certain systems of the body. ... And then there was the idea that medical education increasingly included anatomy and dissection. And the idea of a woman with her hands in a corpse was impossible. No woman worthy of the title "woman" would want to be that person with her hands in a body. So for all those reasons, it was just impossible. It really wasn't a matter of, "Are you good enough?" it was, "You're female. This is impossible."

On how the professors at Geneva Medical College allowed the students to decide whether or not to accept Elizabeth Blackwell as a medical student

The students — recognizing that A) their professors were cowards, and B) this was an opportunity to make serious mischief — had a meeting that night and basically beat any dissenters into submission and presented a unanimous front the next morning that, yes, we definitely want this ... "lady" medical student [to study with us]. The students assumed that it was a prank being played by a neighboring medical school. This was a fairly unpolished group of provincial boys, and they were seeing the opportunity for some good fun. And then they sent their response back to their faculty and forgot about it until several weeks later — a young woman walked into the lecture hall.

On Elizabeth Blackwell not looking favorably on the women's suffrage movement, which was happening while she was in medical school

The medical school that she ended up in was in Geneva, N.Y., right near Seneca Falls, in the Finger Lakes. She was right there. And yet she really looked sideways at those women, who really wanted to recruit her to their side. She was doing something very visible and very stunning, and they really wanted her to be part of their movement. She laughed in a way — or at least scorned what they were trying to invite her to do. I think she called the Seneca Falls conference "the Seneca Falls absurdity." She really believed that there was different work to do first. And she chose medicine because it was an unusually graphic way to prove this idea that women could do what they wanted to do by virtue of toil and talent, not anything to do with their sex.

On how it was for Emily Blackwell, following in her sister's footsteps

Geneva College itself, having given Elizabeth a degree at the top of the class, politely but firmly said, Emily, we are not interested in having you here as a student. We've had enough with women medical students. The issue was that just at the time that Elizabeth was receiving her medical degree, women's medical colleges were beginning to open, because there were more than just these two women who were interested in receiving medical degrees.

But the world was so horrified at the idea of men and women studying medicine together that in Philadelphia and in Boston, women's medical colleges had opened. So if you were a woman who wanted to pursue medicine, that was the obvious thing to do. It was much easier for the male medical colleges to reject you because they could say, why do you need to come here? Go there. That's for you.

Emily, though, and Elizabeth, did not esteem these women's medical colleges highly at all. They just concluded that any women's medical college is going to be, by definition, inferior, mediocre — that a truly impressive degree would only be earned from a men's medical college.

So Emily was not going to be bested by her sister and take a degree from a women's medical college. So she struggled and received, I would say, more rejections than Elizabeth, because the Blackwell name was now a thing. But she insisted and eventually found her way to a place at Rush Medical College in Chicago, which was wonderful. And she had a wonderful year there. And she found a wonderful patron among the faculty and was doing great until he decided to take a sabbatical. And the trustees of Rush said, could you please not come back for the second term? Thanks.

And so she was left high and dry and — being just as determined as Elizabeth — managed to get herself to a place at Cleveland Medical College, which is now Case Western, to finish her second term and receive her diploma. She was just as much of a force.

On Emily's legacy more in the practice and Elizabeth more as a writer about public health

They died within months of each other in 1910. There was a huge gathering at the New York Academy of Medicine to honor their lives, and the speakers honored both of them, of course — honored Elizabeth's pioneering achievement.

But none of the speakers had known Elizabeth in the last 40 years because she'd been gone [in England], and all of them had a deeper professional connection to Emily as this major figure in the New York medical scene. And, so, when you read the eulogies that happened that day, the eulogies for Elizabeth were rather more formal, talking about her as if she was sort of an idea more than a person. But the eulogies for Emily were really warm and and deeply respectful and admiring.

Sam Briger and Kayla Lattimore produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Deborah Franklin adapted it for the Web.

Copyright 2021 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.