Part one of a two-part series.Part one of a two-part series. Read part two here.

In the movie "Contagion," a character played by Kate Winslet demonstrates an over-the-top version of how contact tracing works. Winslet is a CDC epidemiologist quizzing co-workers about who their virus-ridden colleague might have had contact with.

"Barnes picked her up from the airport," says one co-worker. Cut to Barnes on a bus looking really sick. Winslet calls his cell phone as she rushes out of the building and into a car.

"I really need you to get off that bus," she says as the car speeds off in search of the bus. "It's quite possible you've come into contact with an infectious disease and that you're highly contagious."

In real life, a contact tracer wouldn’t likely go to the extreme of actually racing to meet the person at a bus stop. But aside from the Hollywood drama, it’s a pretty good demonstration of how contact tracing is done.

At the beginning of the year, many of us didn’t have a clue of what contact tracing meant. But going forward, it’s something that will touch most, if not all of our lives as we work to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

RELATED: Contact Tracing: How Does It Work?

State and local officials say it's a key element to lifting stay-at-home orders and reopening the economy. And San Diego County is now in the process of ramping up a program.

Lots of leg work

Contact tracing is not a complicated concept. It simply means tracking down everyone who might have interacted with someone with a disease like COVID-19 and telling them to stay at home for 14 days.

"We help that sick person, and those exposed to the sick person, isolate themselves, to stop further transmission of the virus," said Eyal Oren, who led contact tracing for Seattle's King County until 2012 and now is an infectious disease professor at San Diego State. "If one contact tests positive, they become a case, and that same idea would follow."

If we stayed as isolated as we have for the past couple months, tracking down contacts wouldn’t be that hard.

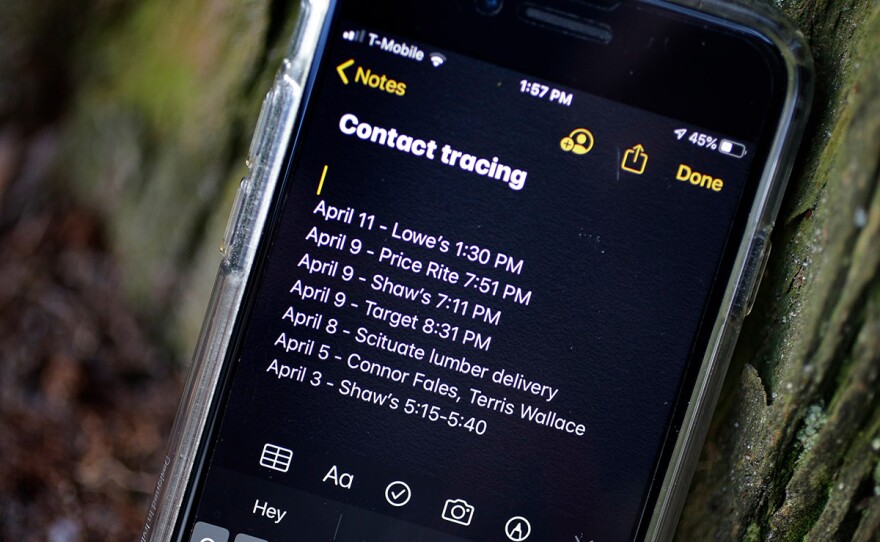

When someone tests positive, a contact tracer would need to get in touch with that person's immediate family, maybe the checker at the grocery store she visited, and if she went into work, whomever she spent time with there.

If one of those contacts tests positive, the process starts all over again with that person's contacts.

But as we begin to reopen society and people go back to work and school, the contacts who need to be tracked will increase exponentially. The standard definition of a contact is someone who was within 6 feet of a person for at least 10 minutes — so fellow patrons at a restaurant, close friends, coworkers, or maybe the passenger near you on the bus.

In Massachusetts, which has already begun an aggressive COVID-19 contact tracing program, state officials are in the process of hiring 10,000 contact tracers. If someone does test positive, they are required by a public health order to stay home for 14 days, said Kelly Driscoll, who is running the program there. But the person's contacts who don't show symptoms or don't test positive are only requested to stay home, not ordered.

Dating back to the Spanish Flu

Contact tracing goes all the way back to the Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918, said Stewart Baker, who was the head of policy for the Department of Homeland Security and managed other virus outbreaks. In recent times, it’s been most often deployed in the realm of sexually transmitted diseases.

On one hand, contact tracing is much easier with sexually transmitted diseases like HIV "because those contacts are more memorable," Baker said. However, with such stigmatized diseases, it can be harder to get those who've tested positive to come forward and name the contacts they've had.

Contact tracing is also credited with helping stop the spread of SARS, the deadly respiratory virus that ravaged China and other parts of Asia in 2003. But COVID-19 brings a new set of challenges, said Eyal Oren, the infectious disease expert at SDSU. For one thing, many people who are infected by the new virus are asymptomatic.

"The need for rapid case identification is really important," Oren said. "We know people can transmit the virus before they've had symptoms, so we have to find and quarantine people really quickly."

Traditionally, contact tracers get in touch by phone, but that can be a challenge if the person doesn't answer the phone, is homeless, or otherwise difficult to find.

"The estimate is you need 30 workers per 100,000 people, and that's double what you usually need," Oren said. "Most places don't even have what you'd usually need because of budget cuts."

State and local programs

On Monday, Governor Gavin Newsom announced California is planning to train up to 20,000 contact tracers to supplement counties that need additional staff and will work with universities to run a training program for contact tracers.

San Diego County is still in the early stages of developing its program. Officials say they are planning to hire 450 contact tracers, about half of what Oren recommends. San Diego County Supervisor Nathan Fletcher said during a news conference Monday that the county could increase its staffing in the future.

RELATED: Would You Use a Contact Tracing App?

One thing is certain, the county won’t have trouble finding people who want to do the work. County officials quickly took down an ad on the HHSA website last week after it got more than 1,000 applicants.

But it still could be months before any program is fully up and running. Consider that Massachusetts started its program a few weeks ago, but it has only hired about 1,000 of the 10,000 people it wants making calls.

States and local governments — including San Diego County — are also considering using smartphone apps to automatically tell the government who people have been in close contact with. But Oren, the infectious disease expert, said those apps can't replace the detective work contact tracers do.

"Contact tracing has a great tradition of being on the ground and tracking the person, place and time, doing direct interviews to find out where people have been," he said. "Phones don't replace that type of information."