This is the final story in a three-part series. Read parts one and two.

The scanner beeped in Berkeley Police Lt. Spencer Fomby's SUV and a scratchy voice came over the radio.

"We have a patient wearing a ski mask and clutching a beer, says he may be robbing a bank," the dispatcher said. Fomby turned his SUV around and sped through the narrow, twisty streets toward a small hospital near the UC Berkeley campus.

"There are two hospitals that we take people to if they’re in mental health crisis," he said as he drove. "This is one of them calling us. Their security is requesting the police to secure the person."

As the shift lieutenant, Fomby’s job was to oversee a team of officers as they engaged with the man in crisis. When the officers arrived, they took a specific approach.

"If there’s not an immediate threat to the officers or some other person, then, most of the time, the officers can slow things down, take their time and start to call resources and start to coordinate a response to the problem instead of taking individual action or using force immediately," Fomby explained.

Berkeley officers use other tactics as well, such as using their squad car for cover and designating one officer to do the talking, so the person doesn’t feel confused or threatened. In this case, a female officer was already there talking to the man, so Fomby hung back.

"I'm not going to come immediately in his face because I can tell from what he's saying and his demeanor and what he's wearing that he may be going through a crisis," Fomby said. "So if I come up and get close to him, I may become a distraction to whatever she's trying to accomplish."

Ahead of the curve

De-escalation is becoming a buzzword in police agencies, including here in San Diego. The term means police officers engaging with the public in a way that's not threatening so situations don't get out of control and lead to violence.

This week, the San Diego Police Department announced it would create a de-escalation policy, something activists have requested for years. In January, San Diego and other local law enforcement agencies began rolling out de-escalation training to their officers to comply with a new state mandate. In San Diego, officers will take 10 hours of the training. District Attorney Summer Stephan said only 700 of the 5,000 local officers have taken the de-escalation training.

POLICE ACCOUNTABILITY FILES: Search The Database Here

Berkeley is way ahead of the statewide reform effort. Four years ago, Fomby was tapped to create a new tactical plan with de-escalation as its central focus. It goes beyond mandating that several hours of de-escalation instruction be tacked on to an existing training program.

"It's a part of every training we do," he said. "So if we do defensive tactics, if we do firearms training, we just had specific less-lethal training, in all of those we're talking about the tactics, we're talking about opportunities to de-escalate, we're talking about reasonable force in each situation."

When Berkeley officers use force, they use many of the same tactics as other departments, though Tasers and carotid restraints have long been banned there. But the department’s mantra is to do everything possible to avoid using force. This means approaching people in a way that doesn't agitate them allows officers to protect themselves.

"If the person complies, we don't have to use force," Fomby said. "We assume a person is not going to comply and we have tactics to mitigate that. If we rush in and create an intense confrontation then it's more likely we're going to get into a gunfight."

In his 19-year career, Fomby has been involved in four incidents that ended with an officer shooting someone.

"We can't avoid officer-involved shootings all together, but with certain approaches, certain tactics, we can minimize the chance we'll get into deadly confrontation," he said.

But Berkeley hasn't had an officer-involved shooting in eight years.

Foundational changes

Fomby said de-escalation involves a shift in attitude for police. It's less about issuing commands and demanding they be followed and more about figuring out how to best approach someone in a way that will not lead to aggression. This is particularly helpful in Berkeley, he said, where the majority of calls are for mental health issues.

"If you're an agency that instills, 'we don't take any mess from anyone, anybody who mouths off,’ you can create officers who are a little bit more aggressive," he said.

The training Berkeley officers receive also puts an emphasis on how race impacts the relationships between police and the public, Fomby said.

”We're looking at implicit bias training, racial profiling, doing assessments of stop data and try to figure out where those disparities lie," he said. "If you combine those two things, you can really get to the heart of the problem or try to affect it in some way."

The Berkeley PD has changed its officers' behaviors in ways that other departments are only beginning to grasp, said Philip Stinson, a former police officer and professor of criminal justice at Bowling Green State University.

"It's a department-wide initiative. It's something that the chief believes in all the way down to line officers," he said. "And they really take the opportunity in all types of situations to re-imagine how they are handling situations. Instead of what we see in many police departments where officers are very quick to race into a situation, they're actually stepping back, assessing the situation, trying to get tactical advantage by understanding all the facts."

Stinson worries that other departments will fail to realize they need to build a new foundation, not just put up a new facade.

It won't work if it's just periodic training in small blocks "where it's something nifty that we're doing," Stinson said. "We have to change the way that police officers go about their day-to-day activities and their interactions with citizens."

'Something's gotta give'

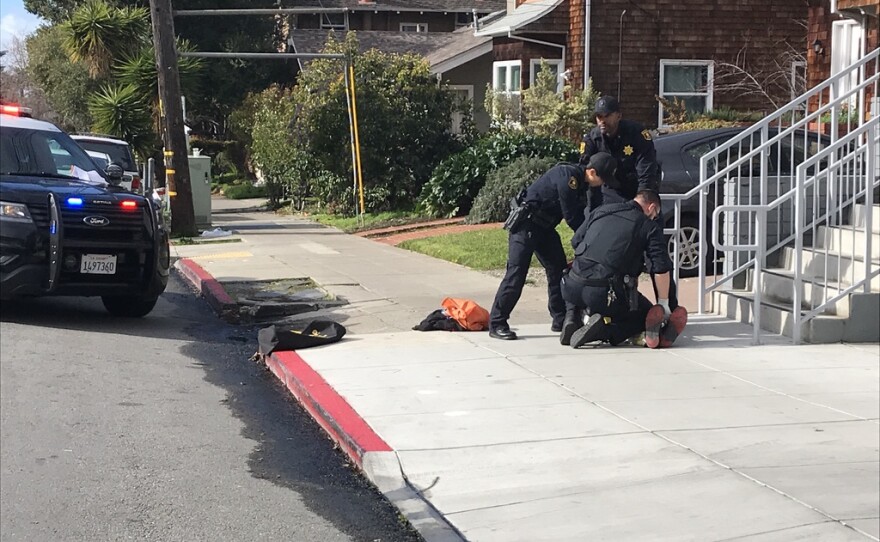

On the call Fomby answered about the man wearing a ski mask, the situation did escalate.

"Each step we're attempting to de-escalate, if he just sits there with the handcuffs, fine," Fomby said.

But then the man tried to put the handcuffs in front of his legs, so the officers held him down.

"Now we have to escalate to control him so he doesn't run or fight," Fomby said. "We decided to put him in a WRAP (a restraint device police can use when they are unable to subdue a person). In a lot of cases that will make people calm down."

But that didn't work. Instead, the man twisted his body, kicked his legs and spit on the officers. So they put a spit hood on him, which is a breathable head covering. They eventually picked him up and moved him into a police SUV.

"Then we can't deescalate because he's headbutting people and it just went from there," Fomby said.

Officers called an ambulance, and the EMTs gave the man an injection of a sedative and took him to the hospital. But even that approach drew criticism from a small crowd that had gathered to observe the incident.

Berkeley PD's use of WRAPs and spit hoods is controversial in the community. There are concerns they limit breathing.

"Stop, you're hurting him, he has mental health issues," a man walking down the street yelled at the officers.

"Sir, we know," Fomby told him.

Mohamed Shehk, a spokesman for the advocacy organization Critical Resistance, said while Berkeley PD gets positive attention for its de-escalation policy, he would like to see the police budget reduced and more money spent on mental health services.

"We don't think it's useful to waste resources and funding on de-escalation training for police officers when police officers themselves are an escalation when they show up," he said. "Police show up with a gun and badge, and they escalate the situation. Instead, we need trained mental health clinicians."

Fomby said he understands the community's concerns and wishes police weren't called to mental health stops.

"That's a person who needs long term mental health treatment, what are we saying as a society? What are we saying as a state?" he said. "I believe police should not be first responders to mental crisis calls. Somethings gotta give, because if people want better outcomes and want to see better results, something has to happen, because the public, they're calling us to deal with these situations"