This is a special six-part series called Dr J's. A new story will be published every day.

Late one evening a few months ago, I climbed into a big white church van with Reverend Ray Smith. He's been leading the United Missionary Baptist Church in Skyline for 15 years and was going to drive me around the neighborhood.

He started our drive with a prayer.

"Come on let's have a word of prayer," he said, bowing his head. "Father we just pray now that you would bless us as we travel now, as we tour the district. We just pray for safety and security."

Pretty quickly, it seemed like we needed it.

Reverend Smith was not the best driver. Soon after we started out, we almost rear-ended a car. A little while later, he attempted to make a U-turn on a narrow street in his giant boat of a van.

Then Reverend Smith stopped driving and got out of the van. To show the lack of lighting in a park, he walked us into the pitch black, up to a couple sitting at a picnic table with their pit bull.

The dog started barking a lot as we approached, but Reverend Smith was unmoved.

"This is what we got at night time," he said, ignoring the dog. "We got one little bitty light, but the whole park should be lit. We have people here, but we should either have lights or put a fence around the park. Do something!"

The people in the park were not thrilled about someone showing up with a video camera and recording equipment unannounced, and asked not to be recorded. We talked to them a bit about why they were out at night — they had nowhere else to go, they said — and then left.

We also stopped in a vacant lot to have a conversation with a man who seemed to have just done some drugs. I saw him put a vial into his pocket when we pulled up and he kept sniffing as we talked.

Then we stopped at a busy intersection where people like to hang out and drink and hopped out of the van to talk to people. Again, they weren't happy about having us approach with a camera.

Reverend Smith's point in all of this was to show that there are still a lot of improvements his community needs.

He said yes, the shooting at Dr J's caused the community and the rest of the city to wake up to how bad things were in his area.

"It brought some light to the crime problem that was happening right in front of our faces," he said. "It showed there needed to be some more community intervention, more police intervention, more business intervention, more political intervention."

After the shooting, he said things did improve, but only for a little while.

"I think it got better, but then it got worse," he said. "It got better for six, eight months, a year, two years, but then it got worse."

Then he slowed the van to point out what used to be Dr J's Liquor. Now it's called Island View Market. The owners changed the name after the shooting.

Reverend Smith said the shooting galvanized the community. But like happens so often, after a few years people stopped paying as much attention and apathy set in. He said there's still crime in his neighborhood, still a lot of problems he'd like fixed. He sees them everywhere he looks: abandoned phone booths he wants removed, trash in vacant lots, not enough street lights.

Crime rates and police presence

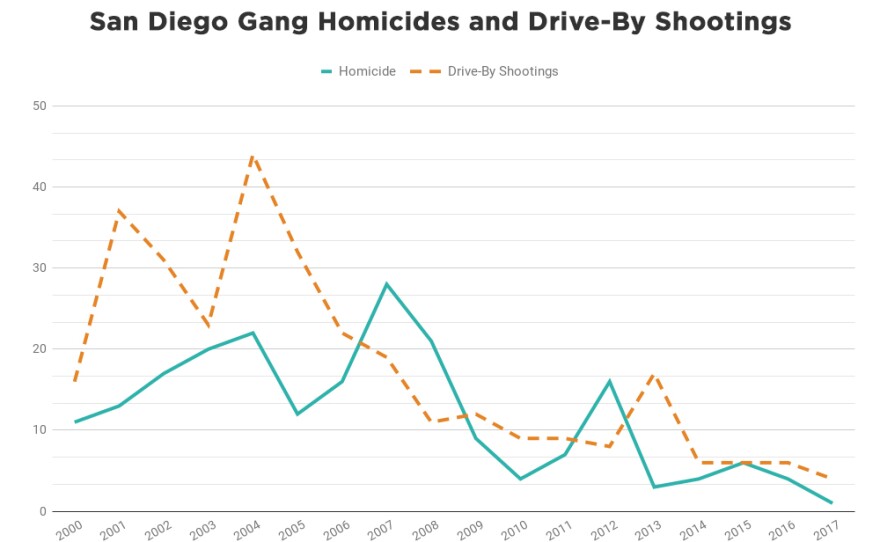

One thing that definitely changed in the more than 15 years since the Dr J's shooting: gang violence has gone down. There were 17 murders that police attributed to San Diego gang members in 2002, the year leading up to the shooting, and 31 drive by shootings. In the next few years after the shooting, those numbers continued to climb a little, but they peaked in 2007 and then started really dropping.

There haven't been more than 10 gang murders a year since 2013. And in 2017, there was just one.

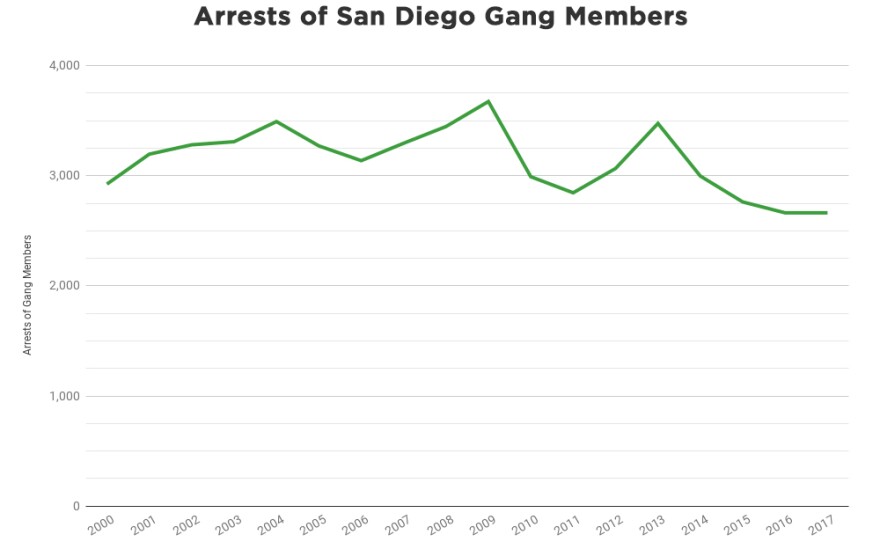

To Laila Aziz, those dropping numbers mean it's time to rethink how the city does its policing. She's a head of the criminal justice reform advocacy group Pillars of the Community and a longtime resident of Southeast San Diego. She thinks there should be reduced sentences for a lot of crimes, less policing of gangs. She said over-policing people turns them into criminals, when really we should be helping them not become criminals in the first place.

"The policies have hurt more than they've helped," she said. "The lock-everybody-up-and-throw-away-the-key is not going to help because you're still going to deal with the problem 10 years later, because you've left their children traumatized with no guidance."

A similar argument is being made across the country right now, as politicians even on a national level tackle criminal justice reform and look at how lengthy sentencing and heavy policing may be doing more harm than good.

For example, the San Diego Gang Commission, an advisory board started because of the Dr J's shooting, wrote in its initial report back in 2006 that the city should focus on "Directed patrol with a general deterrence strategy saturating a high-crime area with police presence, including stops of as many people as possible for all offenses."

Aziz said that's exactly the wrong approach and that it hurts her entire community.

"What does that mean for someone like me who lives in this community when every day I'm stopped just because of what I look like and where I live?" she said. "You criminalize everyone in order for you to get what you perceive as a gang member. I live in this community and I can attest that's not positive."

Not surprisingly, San Diego Police Lt. Manny Del Toro sees police's role in the community differently.

"It would nice if you got to a time where we didn't need police or need as many," he said. "I think part of the reason crime is down is we do keep the pressure on."

Del Toro has been with the San Diego Police Department for almost 30 years and spent a lot of time in the Southeastern Division. He said continued enforcement is necessary, but he also wants police to focus on other parts of the job than just arresting people.

He said police serve two functions, which they call weed and seed.

"The weed was weeding out the bad elements," he said, meaning using undercover officers to buy drugs and making mass arrests.

"Hit it hard from the law enforcement side and get the bad element off the streets," he said. "And also seed the community with good things and positive things that we were hoping would catch on."

That means helping people start neighborhood watches and doing community outreach events like turkey giveaways, holiday parties and visiting schools.

And this, he hopes, can be the future of the police department, that they can hire more officers who are interested in serving the community, not just enforcing its rules.

What's to come?

More than 15 years after the Dr J's shooting, a lot of people are thinking about what's next.

People like Aziz and Reverend Smith are thinking about what they need for their community — how they want the government and police to change, how they want more local jobs and improvements like street lights and trash pick up.

James Carter and his family are looking for what's next, too. Carter is out of appeals in his trial, but he and his mother still have hope that a group like the Innocence Project might take his case.

Carter was also just transferred to another jail near Bakersfield. Jail officials won't confirm why, but it will make him closer to his family so maybe his son can visit.

The families of the women who were killed in the Dr J's shooting are looking forward too. Janise Waites, the young girl who was in the car, is in college now and wants to be an environmental lawyer.

"It caused my mom to grow up and become a lot stronger," she said. "I think if my grandmother had still been alive she probably would have gotten to enjoy her 20s more and would have been less stressed out because she had a kid with her. So it helped her in a lot of ways, but it hurt her in some ways too."

Her mom Tonya Waites, who lost her mother in the shooting, said she is trying to focus on the future, trying to do the best she can to take care of her own children.

She said it only hurts her to look back.