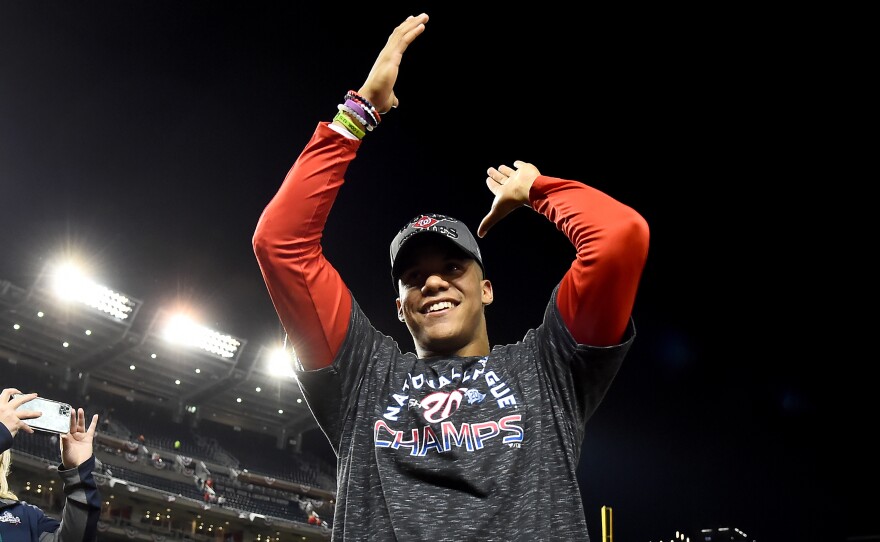

The Washington Nationals return home to face the Houston Astros on Friday, having won the first two games in the World Series. Throughout the series, the heroics of the Nationals' Juan Soto, who turns just 21 today, sparked dancing that stretched from the team's dugout to his native Dominican Republic and its town of Boca Chica, home of the Nationals' Caribbean baseball academy.

It's there that scores of young ballplayers dream of following in Soto's tracks to a lucrative major league career. The academy accounts for a slice of the millions of dollars that baseball teams spend every year recruiting and training Latino players – an economic boon for the Dominican Republic, but a source of scandal as well.

In 2009, a federal investigation found that one promising young player at the Nationals operation in the Dominican Republic was using a fake name and was in fact 20 and not 16.

The Nationals have come a long way since then. Now the team is enjoying distinct success from its rebuilt Dominican operation, infusing its season with a Latin exuberance.

"I love seeing the impact of that Latino spirit and zest for the game," says Adrian Burgos, who teaches U.S. Latino history at the University of Illinois and has written several books about Latinos in baseball. "The game is evolving to include that passion that Latinos have for the game, the enjoyment they bring."

The fun-loving Soto even brings the dancing to the batter box. He sometimes annoys opponents with what's called the "Soto Shuffle," a routine he first used to psych out minor league pitchers.

"I just try to get on their minds and all this stuff," Soto told reporters. "It fuels my confidence."

While the Nationals are relishing special success this year from their Latin American conduit, they are not alone. Their World Series opponents, the Houston Astros, also have a Latino-rich roster: Nearly half of each team was born in Latin America or is of Latino heritage, says Rob Ruck, a history professor at the University of Pittsburgh who has studied baseball in Latin America and is the author of The Tropic of Baseball: Baseball in the Dominican Republic.

This World Series, in fact, may have more Latino players than any before, he says.

"What struck me about these players is the incredible diversity that they represent," Ruck says. They include six Venezuelans, four Dominicans, three Cubans, two Puerto Ricans, a son of Panamanian and Puerto Rican parents and a Brazilian.

Latin America has filled about 30 percent of major league rosters for more than a decade, after growing steadily amid a "Latinization" that began decades ago. The lure of major league riches, such as the $1.5 million signing bonus that Soto got as a 16-year-old in 2015, easily fills academies in the Dominican Republic, where every major league team hosts its own facility.

The Dominican academies have become the preferred route to the United States for foreign-born Latinos. It's an industry that's likely worth a half-billion dollars to the island economy, Ruck estimates.

Critics point out that American baseball teams spend so much on Latin American talent because it's cheaper than developing youth at home. And many of those Caribbean prospects quit school at ages 13 or younger to get training from scouts not affiliated with U.S. teams, who can't sign players until age 16. Once signed by the major league academies, players get free room and board but often little schooling. Few will make it through the system to professional baseball. Most of the young hopefuls get tossed aside with little education and no good prospects.

Repeated scandals have erupted amid baseball's recruiters and academies. Just two years ago, the league banned or suspended Atlanta Braves executives for improperly funneling bonus money through straw men, losing more than a dozen prospects, mostly Dominicans. The Nationals' general manager lost his job in 2009 after the identity-faking scandal made headlines.

The Nationals rebuilt their Caribbean system and opened its shiny new academy in 2014. Juan Soto came through there, as did the team's other emerging Dominican star, Victor Robles, and numerous prospects in the team's minor league system.

But it's a journeyman Nationals player from Venezuela, Gerardo Parra, who's given credit for injecting the team's clubhouse with Latino vitality.

"He brings a lot of energy to the team, no doubt," Aníbal Sánchez, another National from Venezuela, told reporters earlier in the playoffs.

Critics have often misunderstood the fun that Latino players bring to the major league game, says Burgos, the Illinois professor. "For decades, it's been misinterpreted as not caring, not being serious about the game."

Key to the eruption of Latino spirit is the Nationals manager, Davey Martinez, himself of Puerto Rican descent.

"It's crucial — the culture is rooted in the organization and management," says Burgos, whose books include Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line.

But baseball's hiring of Latino managers has never matched its signing of players. This year began with four managers of Latin descent, or about 13% of the 30 teams, in a league where Latinos comprise about 30% of the players. Martinez coached for years in the major leagues before he got a shot at managing, which is typical for Latinos, Burgos says, adding that teams often hire former white players with little coaching experience.

"Somehow, baseball still finds reasons to not hire Latinos."

But that might be changing, as the Latino baseball culture is allowed to flourish. The reggaeton music that's often heard in the Nationals clubhouse is notable not only for its Latin American roots but for how it's sprinkled with baseball references, much as basketball appears in American hip-hop, Burgos says.

It's great to see American-born players embrace the music, the dancing, the culture brought by Latino players, he adds.

"There's a joy to their game that Latinos try hard to never lose."

David LaGesse is a freelance writer based in St. Louis, where he endured the Soto Shuffle as the Nationals swept his beloved Cardinals.

Copyright 2019 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.