Companion viewing

"Ghost in the Shell" (1995)

"Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex" (2002)

"Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence" (2004)

The live action remake of the 1995 anime "Ghost in the Shell" stirred initial controversy for casting a white actress in the lead role. But Scarlett Johansson proves to be the least of the film's problems.

Imagine if someone remade "2001: A Space Odyssey" and inserted characters who continually spouted plot exposition to make sure you did not exercise any brain cells to consider for yourself what was happening on screen. Or imagine a remake of "Citizen Kane" where after the title character whispers "Rosebud" on his deathbed in the opening scene someone came in and explained that Rosebud was the name on his childhood sled, and it represented something that he lost.

The new "Ghost in the Shell" remake essentially commits that kind of offense. It removes all mystery and complexity in favor of a more mainstream and less challenging sci-fi action film. The Japanese "Ghost in the Shell" animated film (based on the 1989 manga written and illustrated by Masamune Shirow) was also a sci-fi thriller, but it wrapped that in a cerebral, existential mystery.

"Ghost in the Shell" (1995)

Directed by Mamoru Oshii, the original "Ghost in the Shell" movie was influenced by both the visual style and themes of Ridley Scott's 1982 "Blade Runner." But Oshii also endowed the film with a uniquely Japanese take on themes of identity, artificial intelligence, robots and what makes one human.

The film served as a wake up call to international audiences that Japan was the place for adult animation. The film introduced audiences to Batou, a gruff government officer, and Major Motoko Kusanagi, a human-cyborg hybrid. The ending of the 1995 "Ghost in the Shell" raised more questions than it answered about what it means to be human. In the years since that film was released, there has been a Japanese TV series, "Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex," that dealt with similar themes but played out with more action, as well as additional feature length movies. Oshii, however, was only involved in the original and its direct sequel, "Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence."

In "Innocence" the line dividing humans and machines grows even less distinct. In fact, humans barely remember what it means to be entirely human. Throughout the film, Batou encounters robots that make him question what it means to be human and the need humans have to create robots in their own image, themes also raised in the first film.

Both of Oshii's films offer dense science fiction that contemplates the ever-shifting nature of personal identity in the modern world. His films are made for adults or at least mature audiences who can appreciate his dark, cerebral musings. His films tend to be a mix of simple, basic plots wrapped in incredibly Byzantine narrative structure and thought. His characters often quote the Bible, Milton and Descartes, and actually carry out intellectual debates in between action set pieces. His endings are enigmatic and deliberately do not answer questions raised but rather provide a kind of poetic final imagery that sums up the complexity of the issue.

"Ghost in the Shell" (2017)

Rupert Sanders directs the new "Ghost in the Shell" from a script by Jamie Moss and William Wheeler. His adaptation stirred criticism for casting Scarlett Johansson as Major. People complained it was another "whitewashing" of what should have been an Asian role. But if you look at how the characters were drawn in the manga and anime, many, including Major and Batou, do not look specifically Asian. For me, the casting of Johansson was troublesome because it revealed a lack of imagination on the part of the filmmakers. She seemed to have been cast simply because studio executives, having seen her as Black Widow and in the sci-fi films "Under the Skin" and "Lucy," could envision her in the role.

She proves to be fine as Major, but the problem is that the film itself is so deeply flawed that she cannot deliver much more than a suitable performance. In many ways, the studio should have planned to adapt the "Stand Alone Complex" TV series instead of creating a feature film because the series was geared more toward straight ahead action rather than philosophical musing, and that would have provided a better foundation for a potential Hollywood blockbuster.

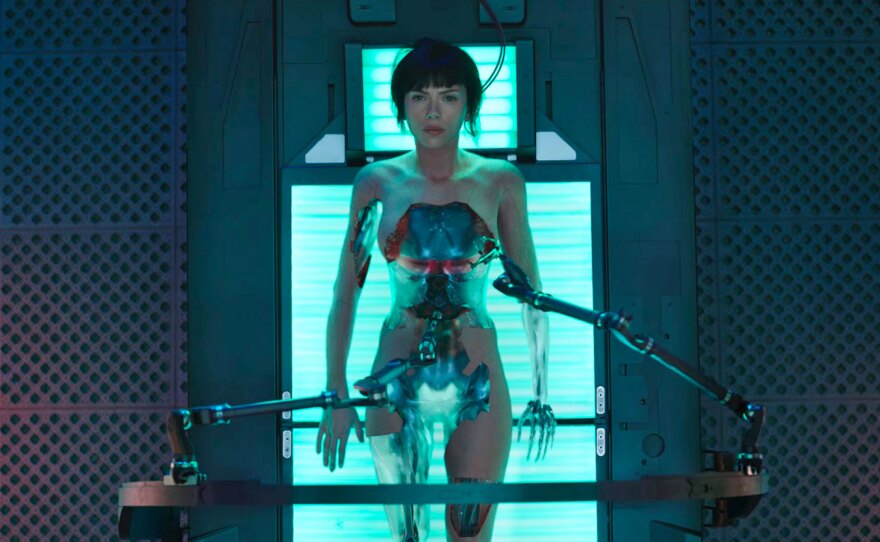

Unlike Oshii, Sanders never wants to challenge his viewers to think seriously about what makes them human. Sanders prefers to TELL us about how his film is going to look at what makes us human. So he has scientists take a human brain and put it into a cyborg body to create Major, and then the scientist (played by Juliette Binoche) explains to Major how her brain provides the memories that are the "ghost" in the shell of her robot body. In the original film, that was part of the mystery to uncover later. The scientist then goes on to explain to her creation that she is the "first of her kind" and a weapon. This sequence is visually almost identical to the one in the anime but the difference is that Oshii never explains anything that we are seeing. He tackles the question of identity indirectly by setting Major off in pursuit of The Puppet Master (a character changed into one called Kuze for the new film), who hacks into the computerized minds of cyborg-human hybrids and talks through their bodies as well as jumping from body to body. This prompts Major to ponder how she defines her own identity, her own humanness.

Sanders' film, on the other hand, wants to explain everything. We are shown how Batou got his robotic eyes rather than to just have him be a character that comes to us looking very different from what we are used to. And Major has to be given a tidy backstory and a clearly defined connection to Kuze (Michael Carmen Pitt), the cyber-terrorist she is tracking. The result is something far more familiar, far less interesting and far less disturbing in the questions it prompts.

The problem with this remake lies in a fundamental difference between what this Japanese anime does and what big budgeted Hollywood pictures need to do. Hundred million dollar Hollywood movies need to appeal to the mainstream and studios think they can do that by providing formulaic films that meet audience expectations and wrap everything up with a sense that everything will be okay. Anime such as "Ghost in the Shell," "Akira," "Gantz," "Elfen Lied" and "Wicked City" are more interested in being dark, enigmatic and questioning, and they do not want to end with an assurance that everything is back to normal and fine. So these Hollywood remakes of anime ("Death Note" will be out soon and the "Akira" remake is once again trying to become a reality) seem doomed to fail on a very fundamental level.

In pondering questions of identity, Oshii favors images that play off of glass, mirrors and water — surfaces that reflect. Major, in the first "Ghost in the Shell," quotes the biblical line: “For now we see as through a glass darkly, but then we shall see face to face.” In "Innocence," Batou says not to blame the mirror if your face looks askew, “the mirror is not an instrument of enlightenment but illusion.” And in a sense, the robots provide a mirror for the humans who create them, they are a reflection of not only the physical perfection they would like to obtain but also of their flaws and foibles.

These kinds of thoughtful, introspective moments do not really exist in the live action "Ghost in the Shell." The ideas are brought up with sincerity but without the poetry and ambiguity of Oshii's film. And while Oshii's Major contemplates her humanity with a kind of investigative calm, Sanders' Major is prompted to think about her identity out of fear. Oshii ends his film with provocative ambiguity, but Sanders ties everything up in a neat, happy package so that a franchise can be born if the film strikes gold at the box office.

For people who have no familiarity with any of the Japanese source material, the 2017 "Ghost in the Shell" will probably strike them as a gorgeous sci-fi actioner that talks a lot about what makes us human. And to them, I probably sound like a curmudgeon who just cannot appreciate a new take on something old. And they would be right, but the reason I cannot accept this new take on "Ghost in the Shell" is because it is just such a pale reflection of the original. It makes a respectful attempt to recreate a lot of the visuals and plot elements from the original, but it has no soul, no humanity.

"Ghost in the Shell" is rated PG-13 for intense sequences of sci-fi violence, suggestive content and some disturbing images. The anime, however, is rated R. And I cannot urge you enough to seek out the original anime and watch it if you have not because it is a breathtaking work of art.

Interview with original "Ghost in the Shell" director

Mamoru Oshii was in Los Angeles back in 2004 to promote "Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence," and I had the chance to speak briefly with him over the phone (and with the help of a translator). My interview offers some insights into why Hollywood studios have such a hard time successfully adapting Japanese anime and manga into mainstream live action films.

Q. The original "Ghost in the Shell" came out almost ten years ago. Why did it take so long for you to make this follow-up film?

A. After completion of "Ghost in the Shell," I was very tired of making animation, very tired of working with animation. I wanted to do something else. So I did some live action ("Avalon"), and I wrote some novels. Then, nine years later, I decided to make this movie, "Innocence." I felt there had been enough time, and I was interested in trying animation again, and this project came to me.

Q. Why do you feel that animation is the best way to express this particular story?

A. Because I wanted to talk about logic, and animation is the best way to express logic as opposed to live action. Live action has too much emotion, there’s too much emotional distraction. So anime is best for logic.

Q. Can you discuss how dolls are viewed in Japanese culture? Ningyo — the Japanese tradition of human-like dolls that can act as a human substitute and must be disposed of in a purifying ritual that is referred to in "Innocence." This is something that Americans may not be familiar with.

A. Well, I respond to your question by actually posing a question to you. What would you do if your daughter had an old doll that was broken and no longer wanted, would you just throw it away like garbage?

Q. Well I have a son and this is something that comes up with his stuffed animals. If we ever get rid of any, we always give them away to someone else. One time, we had placed some of his stuffed animals in a bags to store them, and he put holes in the bag so that they could breath.

A. Well, if that is the case in America, then I think there should be no problem in having them understand, they are the same as in Japan. We don’t consider our dolls as mere objects. They are more than objects. So if they are not objects then what are they? If you have something for a very long time, you can’t just throw it away, it has taken on some qualities that make it more than an object. So maybe if this object has a human shape, then the object is partly human, and maybe, it has a spirit or a soul. If it were in my movie, I would be using the term ghost rather than spirit or soul. That’s what I was interested in exploring in "Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence." That’s why I used dolls. Because in Japan they can’t dispose of things as garbage. If you have something for a long time it develops a soul. So rather than just throw that item away, we go through a ritual to cremate or burn the object so that it’s spirit is set free, or you put it on a boat and let it drift away. So the reason dolls are used is that I wanted to talk about what humans really are, and I wanted to use dolls as a comparison. And then, if you cannot throw away dolls, you can’t throw away robots. If humans are damaged, they can have parts replaced, and then they become part robot. So does a human that is part robot lose his humanity? How can a person be thrown away? These are the themes that I wanted to explore. I wanted to consider the border between humans and robots. And as you look into these issues you discover that that border is very ambiguous. So that’s what I wanted to make a movie about. There are a lot of Hollywood movies that deal with robots, "AI" and "I, Robot," but the difference with those Hollywood movies is that they are interested in robots that want to become human. I do not think there are any movies where a human wants to become a robot.

Q. Your films are very cinematic in the way they use production design and lighting. How do you work with animators to create this?

A. Normally an anime director comes up with a character and the actions and then develops the background to play out the action against. In "Ghost in the Shell," I put a heavy weight on the production design. I created the backgrounds and the production design first, and then decided how to light it, if there is gas or no gas, fog or no fog. This is totally the opposite of standard anime. So the animators don’t like the way I work.

Q. Do you see a common theme running through all your films?

A. Yes. The basic theme hasn’t changed since the very first film. I keep asking what are humans? What is it to be human? But while the basic idea has not changed through all my movies, my approach to that theme is slightly different in each film.

Q. Do your films challenge anime conventions at home in Japan?

A. It has always been a goal of mine to make my films challenging in some way so in that sense a small portion of the audience don’t like my films very much.