To Trunnell Price, 1967 was a vibrant time in San Diego’s black neighborhoods.

“The West Coast was very active in the culture,” said Price, who was then a 17-year-old San Diego State University student from Southeast San Diego. “There were new types of music and new types of dress. It was a very upbeat, robust society in the black community.”

Former San Diego Police officer Terry Morse recalls the city as being a simultaneously conservative military town and a happy-go-lucky place with aspirations.

“It wanted to have the fancy marinas, and it wanted to have the fancy places to go and eat and the Hollywood stars vacationing in San Diego,” Morse said. “They were kind of a wannabe L.A.”

But like most other cities across the country in 1967, communities were segregated along racial lines. Social crossover triggered unease.

“Most people outside of the black community did not want any interaction with the people in Southeastern San Diego, the people in Logan Heights,” Price said.

And there were consequences for straying past the understood geographic boundaries.

“You were stopped by police,” Price said. “You were harassed by the police. “They said, `Get out of here. Go back where you came from.’”

Inside the community, interactions with police were also fraught.

“If we were accosted by the San Diego Police Department for whatever reason, pick one, we were usually taken down by Father Joe’s at the lumberyard and we were brutalized,” Price said. “We were beaten or talked down to or cussed out. And we would have to walk from around 16th and Commercial back to our neighborhood.”

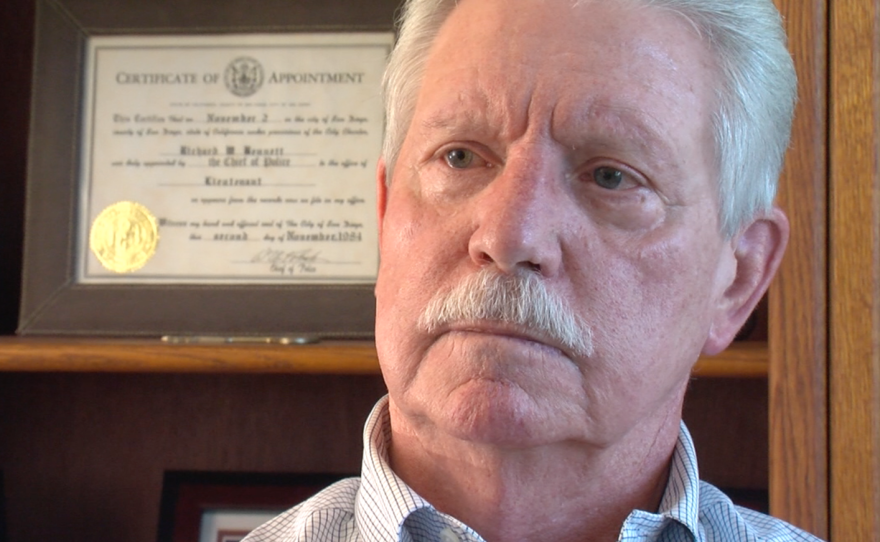

Former San Diego Police Lieutenant Richard Bennett was a rookie officer at the time. He said fear flowed both ways because some minority communities were also high-crime areas.

“At night, we’d pull a car over that had windows that were tinted so darkly, we couldn’t even see who was inside,” Bennett said. “We often wondered if there were going to be guns pointed at us, whether they would cooperate with us or what would happen.”

But Bennett believes police tactics also played a role in the climate of distrust.

“Today, we would ask you and then we would tell you and then we would make you,” Bennett said. “But in those days, it was like we arrived and we told you. People resented that and I understand why.”

It’s against this backdrop the Black Panther Party formed in San Diego in 1967.

Price said the party’s national headquarters in Oakland contacted the Black Student Union at San Diego State and asked members to create a local chapter.

And police brutality was not the sole reason for opening a local Black Panther branch.

“We were also suffering from a lot of social, economic and political inequalities,” Price said.

The local Black Panthers provided meals for the elderly, opened health clinics and served food to the homeless. They also started a breakfast program for schoolchildren.

Price said the party sought to elevate black people by calling for better education, housing, socialized medicine and an end to police abuse.

“We were more excited than the people because we were fulfilling our obligation,” he said.

Former police Lieutenant Bennett admired some of what the group did.

“They had a blueprint for success for black people which I thought was a positive thing but that is not how they interacted with police,” he said. “They drew cartoons of policemen being pigs and being shot by a black person. They’d stand around in their Black Panther berets with their rifles. I was threatened by that.”

In July 1969, there was a riot at Mountain View Park. Panther party chairman Henry Wallace blamed police for the chaos.

“They knew that most of the black people in Southeast San Diego would go to that park on Sundays,” Wallace said. “They came in there like National Guards and stuff and started firing teargas at people and god knows what else. They had pulled out those long bats, those billy bats and were beating on people.”

Wallace said it was symptomatic of the department’s disrespect for the black community.

“When we started burning up businesses and throwing Molotov cocktails back at them, then they had a renewed sense of respect for us,” Wallace said.

In 1967, the FBI created a counterintelligence program called COINTELPRO to discredit and disrupt the Panthers. Strategies included pitting black groups against one another, surveillance, infiltration, raids and other activities.

According to a U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence report, FBI officials helped stoke rivalry between the Panther Party in San Diego and the United Slaves Organization. Two people were killed and four others were wounded as a result.

There was also an investigation into civil rights abuses by San Diego police officers against the Black Panthers.

Retired criminal defense lawyer Richard Savitz represented local Panthers in court. He said police would arrest party members, ostensibly for disturbing the peace. But Savitz said the arrests were really meant to punish people for being in the group.

“It’s a shame but they thought they were ridding the community of communists and bad guys,” Savitz said. “There was just no understanding between the police and the Black Panthers.”

But retired officer Terry Morse believes he connected with a party member during a house raid where he says four group members were living with a white prostitute. He recalled telling the man he believed others were trying to start a racial war.

“I said, `I don’t want to hurt you and I don’t want you to hurt me,’” Morse said. “ I reminded him in the time he had known me he had never seen me hit anybody other than social back talk between Panthers and us, that’s all it ever really was.”

Morse said ultimately, the man agreed with him and he never saw him again.

Another memory that stays with Morse is the feeling he got early one Sunday morning as he was closing out his graveyard shift, driving down Imperial Avenue from 32nd Street to 25th Street back to the station.

“The first thing I noticed was the smell of the barbecues being started,” Morse said. “And then I noticed the sound of choirs being warmed up. It was kind of a warm and fuzzy feeling. That protect and serve part was for everybody and I was glad that I was able to do it.”

Editor’s Note: Thursday, we’ll look at the resurrection of the San Diego Black Panther Party in the age of President Trump.