KPBS is exploring learning at the cellular level in an ongoing education series called "What Learning Looks Like." The goal is to help us understand how learning happens — or should happen — in our everyday lives.

What does the brain look like when you’re playing music? According to students at Kellogg Elementary School in Chula Vista, it’s definitely pink and, if you could shrink yourself down and step inside, a relaxing place to be.

“I imagine a little mattress, but brain, and like in the cartoons when there’s music, there’s little notes in there,” said Abel Beltran, 10.

“I would compare my brain to this toy that I have at home,” said Andrea Sandoval, 10. “It’s like a ball that closes and opens.”

“I think it might move a bit, because as we’re playing music, not only are we playing it, we’re also learning something new,” said Bezalel Shin, 11.

UC San Diego neuroscientist John Iversen said they’re not too far off.

“I think that actually shows some deep insight,” Iversen said. “Even when you’re just listening to music, youre brain is not just sort of passively recording what comes in. It’s actually actively engaging with the sound.”

Iversen just wrapped up a five-year study on the brains of children who play music in the San Diego Youth Symphony's Community Opus after-school program, like the students at Kellogg. He and SDYS want to use the data comparing brain changes in kids who played music and those who didn’t to answer this question:

“Much the same way that increased nutrition might change the path of growth of a child’s height, are there certain activities such as music that might change the trajectory of growth of the brain?” Iversen said.

They hope the answer will make the case for bringing arts education back to public schools.

The music fade-out in schools

For the past few decades, standardized testing has put an intense focus on reading and math in U.S. schools. Educators say that and budget cuts have caused enrollment in arts classes to plummet. In the western United States, the number of students enrolled in arts classes dropped from 35 percent in 2008 to 33 percent in 2016, according to a federal survey.

“The demand that everything be addressing the test undermined other academic learning that wasn’t seen as directly addressing the test,” said SDYS President Dalouge Smith. “Unfortunately, music suffered, when the science shows us that music actually does contribute to learning of language, learning of mathematics, learning of vocabulary. That correlation was not as evident at the time, and we still have to make that case strongly.”

RELATED: It’s Fifth-Grade Music For All Under San Diego Unified Arts Plan

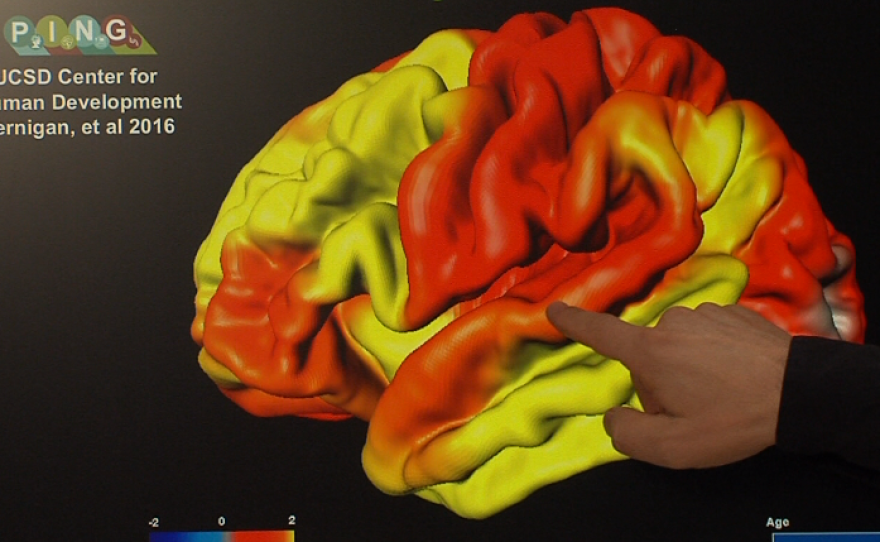

So Iversen and Smith are conducting their own tests — in the form of MRIs and EEGs — to study developing brains, particularly the outer, noodly part called the cortex.

“It’s almost like a crumpled ball of paper. It’s wrinkled up so it can fit inside our skull. But if you were to straighten all of those wrinkles out, you would see it’s just a sheet of neural tissue,” Iversen said. “So what we’re looking at is basically how different regions of that are growing and shrinking over time.”

An orchestra and conductor for the brain

At a very basic level, the ear and brain kind of work like the equipment I used to record my interview with Iversen.

“The microphone is picking up my soundwaves. It’s turning it into a voltage. So that’s kind of like what the ear is doing. But then once we get into the computer, it’s turned into a digital file, so it’s just turned into numbers,” he said. “So that’s a pretty good analogy in some sense for how the brain is recoding things from analog to digital.”

The cochlea turns sound waves into nerve impulses that travel through the brainstem to the cortex. Brain scans show multiple parts of the cortex respond to sound, especially if it has rhythm and lyrics or is accompanied by movement.

Iversen is in the very beginning stages of analyzing his data, but early findings suggest playing music is linked to stronger language development.

“What we found is that the size of the motor cortex, this area that controls movement and planning of movement, predicted individual differences in the ability to perceive a musical beat,” Iversen said. “So it’s suggesting that there’s something about this connection between hearing and moving that may develop this ability to hear patterns in time. And that, of course, is really the foundation of learning language — the processing of sound.”

That’s not to suggest, however, that music makes brains bigger. Think of it more as training the brain, especially the connections we use to learn.

The University of Southern California’s Brain and Creativity Institute released findings in November from a similar study that showed kids who played music not only exhibited thickening of the auditory cortex, but also had more robust white matter, the part of the brain that carries signals through the brain.

“There’s an idea (in neuroscience) that the brain grows exuberantly at first — it actually creates more connections than we end up with as adults — and that over time, experience might prune out some of the connections that aren’t important,” Iversen said.

So playing music at an early age might help the brain cortex function like a well-tuned orchestra. And the better your orchestra, the better your academics.

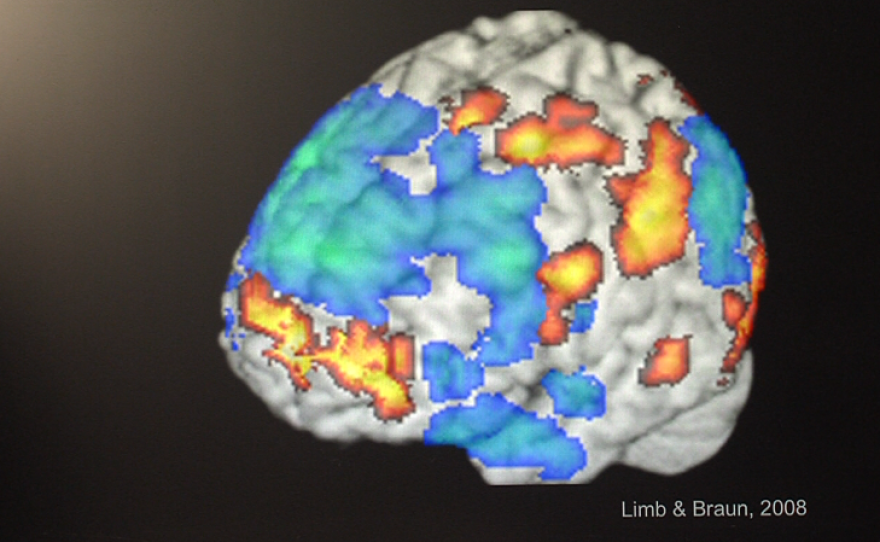

Iversen said another way music might help with learning is by creating a tiny conductor for that brain orchestra. Research from UC San Fransisco scientist Charles Limb shows when they improvise, jazz musicians and rappers suppress activity in the parts of the cortex that control the inner dialogue and make you overthink.

“We tend to think of brain building as muscle building — just make everything bigger and better. But it’s really about control,” Iversen said. “So one thing that this suggests that music helps kids learn is how to regulate their own brain.”

A mother’s perspective

Anecdotal evidence seems to back Iversen up.

“Music did change his life,” Carol Medina told me of her 12-year-old son, Anthony, who has autism. “Bringing him to orchestra here, it just opened a whole new world for him. He had new friends. We started noticing a lot of parts of his learning expanding more.”

Medina said Anthony caught up with his Kellogg Elementary classmates in reading after joining Community Opus. And he seems to have that tiny conductor helping to regulate his thoughts and emotions.

“It helps me when I have stress or more stuff,” Anthony said. “It’s like a good feeling.”

His classmates, too, said they think of music — even chord progressions — when they need to calm down during a test in another subject. And the Chula Vista Elementary School District reports better classroom behavior, improved attendance and deep parent engagement after increasing music offerings at its schools in 2010.

Symphony President Smith said he’s working with other researchers at UCSD to track those more qualitative outcomes in addition to Iversen’s brain research.

“This is not just about giving kids in San Diego County access to music and arts education,” Smith said. “For the San Diego Youth Symphony, this is really about helping the whole of the country understand the importance of this choice and choosing to make it.”

He might want to recruit Anthony.

“I love playing music,” he said, hugging his cello like a close friend. “It’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me.”