Some people may be dimly aware that Thailand's chilies and Italy's tomatoes — despite being central to their respective local cuisines – originated in South America. Now, for the first time, a new study reveals the full extent of globalization in our food supply. More than two-thirds of the crops that underpin national diets originally came from somewhere else — often far away. And that trend has accelerated over the past 50 years.

Colin Khoury, a plant scientist at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (known by its Spanish acronym CIAT) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is the study's lead researcher. Khoury tells The Salt that "the numbers affirm what we have long known — that our entire food system is completely global."

Previous work by the same authors had shown that national diets have adopted new crops and become more and more globally alike in recent decades. The new study shows that those crops are mainly foreign.

The idea that crop plants have centers of origin, where they were originally domesticated, goes back to the 1920s and the great Russian plant explorer Nikolai Vavilov. He reasoned that the region where a crop had been domesticated would be marked by the greatest diversity of that crop, because farmers there would have been selecting different types for the longest time. Diversity, along with the presence of that crop's wild relatives, marked the center of origin.

The Fertile Crescent, with its profusion of wild grasses related to wheat and barley, is the primary center of diversity for those cereals. Thai chilies come originally from Central America and tropical South America, while Italian tomatoes come from the Andes.

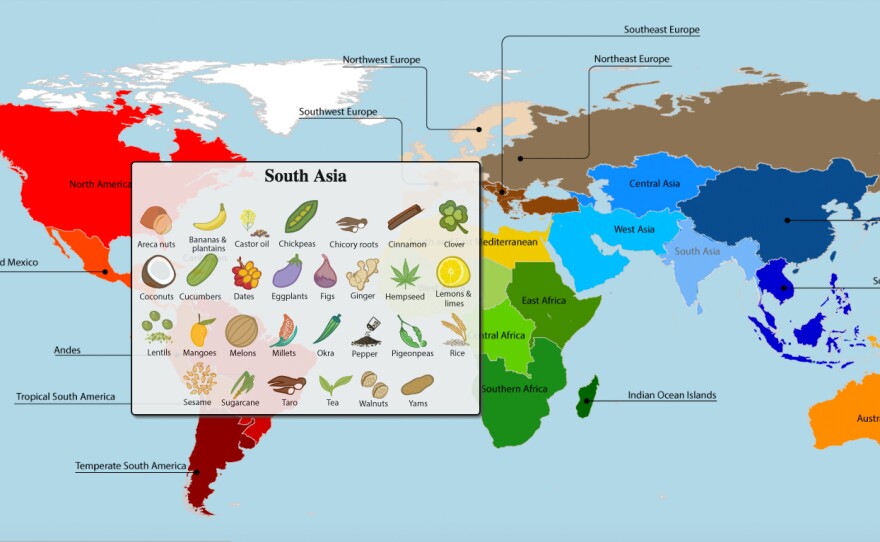

Khoury and his colleagues extended Vavilov's methods to look for the origins of 151 different crops across 23 geographical regions. They then examined national statistics for diet and food production in 177 countries, covering 98.5 percent of the world's population.

"For each country, we could work out which crops contributed to calories, protein, fats and total weight of food — and whether they originated in that country's region or were foreign," Khoury says.

Separately, the researchers looked at what farmers were growing in each country and whether those crops were foreign in origin.

Globally, foreign crops made up 69 percent of country food supplies and farm production.

"Now we know just how much national diets and agricultural systems everywhere depend on crops that originated in other parts of the world," Khoury says.

In the United States, diet depends on crops from the Mediterranean and West Asia, like wheat, barley, chickpea, almonds and others. Meanwhile, the U.S. farm economy is centered on soybeans from East Asia and maize from Mexico and Central America, as well as wheat and other crops from the Mediterranean. The U.S. is itself the origin of sunflowers, which countries from Argentina to China grow and consume.

Paul Gepts, a plant breeder and professor at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the study, called the findings very important.

"Professionals are aware of global interdependence, but this is not something most people have thought about," he says.

CIAT researchers have produced an interactive graphic that allows you to explore the results — Gepts says this could really help people understand where their food comes from. "It shows up on the screen very nicely," he says.

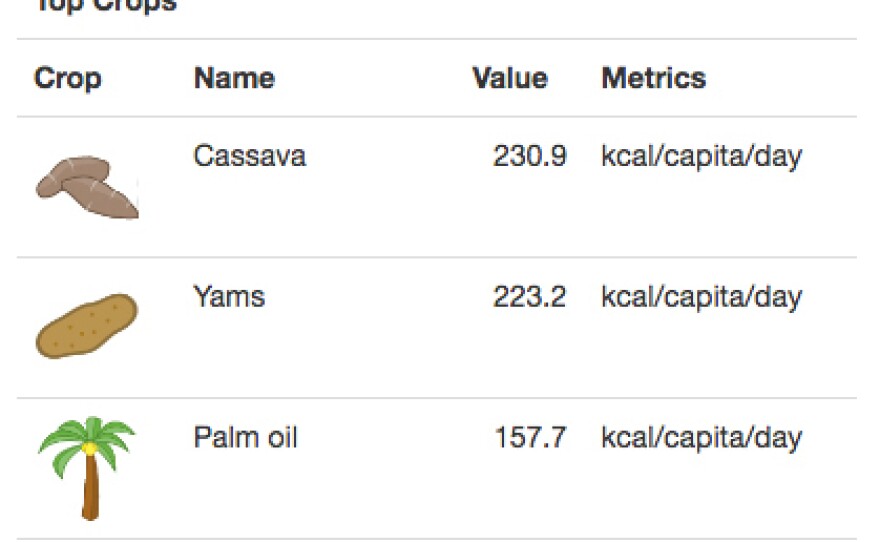

Regions far from centers of agricultural biodiversity — such as North America, northern Europe and Australia — are most dependent on foreign crops. By the same token, countries in regions of diversity that are still growing and eating their traditional staples — for example, South Asia and West Africa — were least dependent on foreign crops. But even countries like Bangladesh and Niger depend on foreign crops for one-fifth of the food they eat and grow. Tomatoes, chilies and onions (from West and Central Asia), for example, are important in both countries.

Furthermore, over the past 50 years, the world's dietary dependence on foreign crops has increased from around 63 percent to the current 69 percent. Khoury says this was "a bit of a surprise."

"Cultures adopt foreign crops very quickly after coming into contact with them," he says, pointing out that potatoes were being grown in Europe just 16 years after being discovered in the Andes. "We've been connected globally for ages, and yet there's still change going on."

Crops grown for fats and oils have seen the greatest change: Brazil now grows soybeans from East Asia, and Malaysia and Indonesia grow oil palm from West Africa.

Global interdependence also extends to the future of crops — for example, to combat the threats of climate change and new pests and diseases. The genes needed to face those challenges are most likely to be found in the primary regions of diversity, but will be needed wherever those crops are grown.

That is a crucial point for Cary Fowler, former executive secretary of the Global Crop Diversity Trust and an author of the paper. He says the study presents scientifically rigorous evidence for interdependence within the global food system.

"That means we need to start behaving as if we are interdependent," Fowler said in an interview.

The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture is supposed to ensure that countries can get hold of the plant diversity they need to develop new varieties so they can withstand future challenges. But most countries, Fowler says, are not providing the "facilitated access" promised by the treaty.

The problem is usually political, as countries ignore the shared access offered by the seed treaty (which about 120 countries have adopted) in an effort to keep any potential benefits to themselves.

For example, during the International Year of Quinoa in 2013, researchers attempted to compare as many different varieties of the Andean grain as they could, to see which might be best in different environments. Of more than 3,000 different known varieties, the researchers could obtain only 21, and none of those came directly from genebanks in the countries of origin.

Other researchers who conducted a deliberate test of the treaty genteelly concluded that, "after nearly 10 years, 'facilitated access' is not straightforward."

Fowler says that this kind of attitude undermines the good intentions expressed in the treaty: "It's time for the International Treaty to be observed and enforced."

Jeremy Cherfas is a biologist and science journalist based in Rome.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.