Dancehall has replaced reggae as the defining music of Jamaica, at least for contemporary Jamaicans. Fans say it’s the voice of the people. Critics say it glorifies sex and violence. In its most basic form, dancehall involves a deejay rapping over a beat.

Because it dates back to the 1970s, some argue it's the source of hip hop.

No one denies that today, dancehall is the most popular art form in Jamaica.

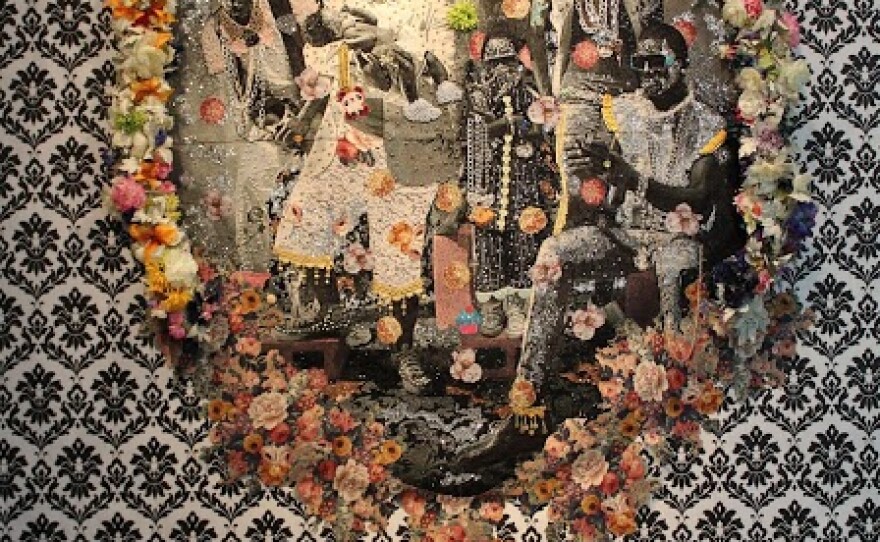

The culture surrounding dancehall is the subject of Ebony G. Patterson's artwork. Her large mixed-media wall tapestries and paintings are on view at the Lux Art Institute in Encinitas through the end of May.

Patterson has always been interested in more than just the music of dancehall.

"It’s language, it’s dress, it’s music, it’s movement and it’s bravado," said Patterson.

Patterson was born in Kingston and splits her time between there and Lexington, Ky., where she is an assistant professor in painting at the University of Kentucky. She grew up listening to dancehall music. Her favorite artist was Bounty Killer, known as the "poor people's governor." Patterson would later go to Passa Passa, the weekly street dance party in Kingston where various dance and fashion trends were born.

Those experiences still inspire her work.

Like hip hop in the United States, the engine of dancehall is the streets.

"It’s always within these inner city communities, these rough experiences, where people use song and dance as a form of expression and as a way of complaining about things that they’re not so happy about," said Patterson.

Kingston’s inner city neighborhoods are bleak. There’s poverty and violence. Dancehall is an escape.

"I like to think of dancehall as this very vibrant, very rhythmic, very colorful and also very camp culture," said Patterson.

That’s what you see in Patterson’s huge, ostentatious wall tapestries. There’s a lot of pink and florals – imagine inner city Kingston meets Palace of Versailles.

She starts with a staged photograph of stock characters from the dancehall scene. The photo is then woven into the fabric. Using sturdy tapestries allows her to add layers of colorful paint, garish jewelry and glitter to the surface. In fact, Patterson spends days gluing glitter.

"I glitter bomb," said Patterson. "I’m the glitterati."

The images are mostly of men. They have hard expressions, typical of the gangster personas glorified in dancehall. Their clothes and jewelry are flamboyant.

"It’s all about how the clothes allow this kind of extended performance," said Patterson. "The clothing becomes a prop to extend this bravado."

Dancehall lyrics are macho and at times homophobic, yet dancehall fashion has become decidedly feminine.

In one of Patterson’s pieces, the tough men all wear tight floral pants. She noticed a shift in dancehall: baggy pants went out and tight ones came in.

"I remember growing up, they always said if your pants were too tight you were suspect. Your sexuality was in question," said Patterson. "And here I was looking at the total opposite of that."

The faces in Patterson’s tapestries draw you in – the characters are black, yet the ovals of their faces are white. Skin bleaching is a trend in dancehall.

"When I think about skin bleaching, I think about skin blinging," said Patterson. "It’s a kind of skin blinging."

Dancehall megastar Vybz Kartel, who was recently convicted of murder, bleaches his skin. He sings its praises in a song called "Cake Soap" and has defended it in the media by saying if white people can tan, why can’t he bleach?

Patterson says some in the dancehall scene talk about lightening their skin in the same way they talk about clothes.

"So I’m going out and shop to get this outfit for this party that’s happening in two weeks but I also have to buy my case of bleaching cream so that I can make sure that my tone is right with that outfit," said Patterson, imitating the phenomenon. "So that when the camera picks me up I glow well."

Patterson says in Jamaica, colorism is a constant problem. Lighter skin is considered better and more attractive.

She says the bling, the hyper-feminine outfits, the skin bleaching, it’s all a performance. An effort to be seen, because in Jamaica’s poor working class communities, people don’t feel seen or valued.

"So I could totally understand then within that landscape of understanding and that landscape of devaluization, why someone would make so much effort in this brief life to perform a sense of importance," said Patterson.

It’s that performance Patterson captures and celebrates so well in her extravagant tapestries.

Ebony G. Patterson’s work will be on view through May 30 at the Lux Art Institute in Encinitas.