In the middle of the desert, a few hundred people live without electricity or running water in a squatter community called Slab City.

On the same far-flung patch of desert in Imperial County, a community of artists is fighting to keep its land — and the art its residents have created. The artists' collective is called East Jesus. The name is a colloquialism for “out in the middle of nowhere.”

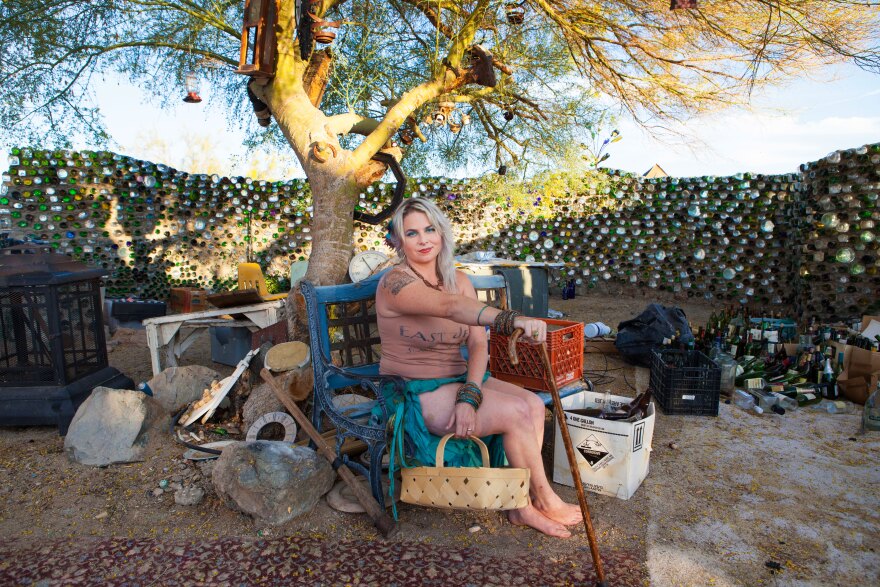

The East Jesus Art Collective, which runs East Jesus, is an artist community and residency program. But it’s also a world unto itself. A universe devoted to art and sustainability, where the human footprint is closely monitored and garbage is used to make art.

East Jesus curator Jenn Nelson lives at East Jesus throughout the year.

“One of the things we look at here is how can we take what would normally go in a landfill and either make it useful again, or make it enhance our lives through the creation of art,” Nelson said.

East Jesus provides a temporary home for artists to work on projects. Visitors can camp on the property, have a meal, take a tour of the sculpture garden and soak up the atmosphere.

“We don’t ask people to leave any money,” Nelson said. “If they choose to, we do have a couple of donation boxes.”

East Jesus is off the grid. There’s no running water, electricity or sewer system. The residents recycle their own waste.

The whole place was the vision Charlie Russell, an artist and regular at Burning Man, the annual counterculture festival held in Northern Nevada. Russell, who died of a heart attack in 2011, came to Slab City in 2006 to work on Salvation Mountain, a massive colorful artwork and tourist draw near the entrance of Slab City. He was inspired to start something of his own. He left a tech job in the Bay Area and had everything he owned brought to Slab City in a shipping container, including two art cars.

“When Charlie Russell first came out to the Slabs, this was the messiest, most trash-strewn corner,” Nelson said. “He took an abandoned field of trash and turned it into a place for contemporary art.”

Part of Russell’s vision was a world without waste, where someone else’s trash could be used for some form of expression. He invited artists to make works for the sculpture garden.

Today, it includes a large-scale sculpture by Joe Holliday of a woolly mammoth made out of discarded tires.

Royce Carlson has many pieces in the garden, including a “mutant albino whale” made out of 4,000 plastic bags.

Resourcefulness extends beyond art at East Jesus. The residents also grow most of their own food.

“We try to focus on exotic varieties or efficient varieties to get the most nutritional value for the water we are using,” Nelson said.

They get their water “trucked in.” Nelson would not elaborate.

Where Slab City residents get their water has been a divisive issue with nearby cities.

Like Slab City, East Jesus residents are squatting on state-owned land.

The state is open to selling the land, and Nelson is worried a solar or geothermal company will try to buy it.

“We’re not going to wait until the bulldozers show up,” Nelson said. “This means too much. “

She set up a nonprofit called the Chasterus Foundation, which allowed her to file an application to buy the land. She said those opposed to Slab residents buying the land are not facing reality.

“People have been allowed to live on this land for free for 40 years,” Nelson said. “At a certain point, you have to recognize this isn’t our land. We’ve been lucky so far. But if you can’t tell that the light at the end of the tunnel is a train, you’re going to get run over.”

It will take months before the state decides whether to sell. And then East Jesus will have to raise money to purchase the land.

“East Jesus has a larger message of hope and living within the future that we’ve created for ourselves,” Nelson said. “It has a larger message about sustainability, about art, about who we are as people. And that’s what we can’t afford to lose.”