Is "poverty porn" making a comeback?

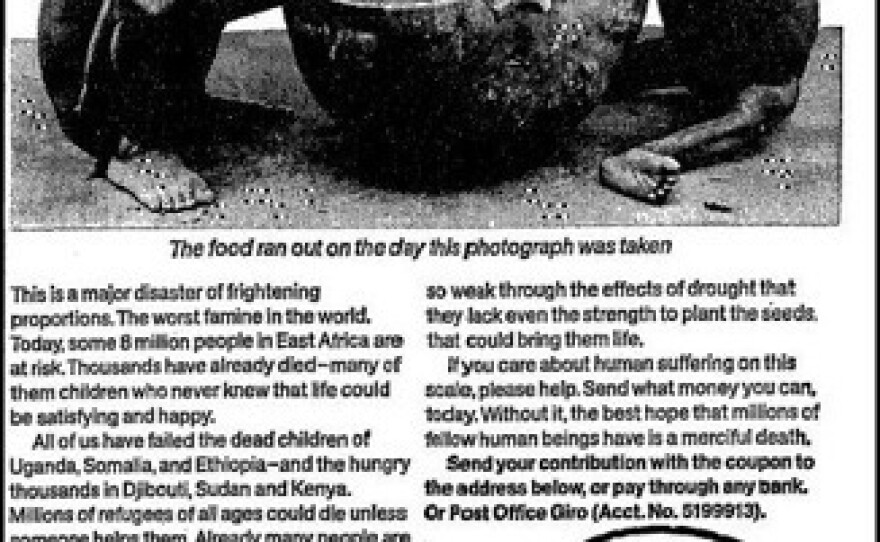

That's the term that some people used back in the 1980s to describe attention-grabbing fundraising ads like the one below:

Back then, the media was filled with images of starving African children in desperate need of food, seemingly all alone in the world. And folks in the West were invited to save them from their misery.

This kind of appeal worked. The ad above, from the UK charity Disasters Emergency Committee for their East African Emergency campaign, brought in $23 million between 1980 to 1984 for famine relief in Ethiopia.

But not everyone thought these kinds of images were appropriate.

"People in developing countries are not incapable or passively awaiting rescue," says Jennifer Lentfer, director of communications at IDEX, a San Francisco-based international grant maker, and a former lecturer on global development communications at Georgetown University. "Poverty, conflict, disasters, injustice is heart-breaking, but it doesn't mean people are victims."

By the end of the decade, the arguments against such images won the day. Nonprofits began using more positive images of the poor to tell stories.

But some observers in the global development community believe exploitative photos of the poor are creeping back as a way to boost fundraising efforts.

John Hilary, executive director of the anti-poverty organization War on Want, described the return of "poverty porn" in a 2014 article for The New International.

"Recent years have witnessed the return of the starving black child as a stock image in the fundraising communications of far too many aid agencies," he wrote. "A battle which we thought had been won many years ago clearly needs to be fought afresh."

The phrase even popped up last night on the new cable TV show Adam Ruins Everything. In a discussion of what motivates people to give to global causes, Teddy Ruge, a Ugandan-born writer who works to develop new businesses in Africa, defined poverty porn as "[finding] the most extreme situations and make it look like the most common situation on the continent."

One widely cited example of an inappropriate image is the 2013 television ad from Save the Children in the United Kingdom, depicting children in various stages of emaciation.

Hilary condemned the aid for what he called its "degrading imagery of children." Other charities and bloggers agreed with him. Dutch activist Frank van der Linde said it violated the European code of conduct on NGO images and messages, which encourages a respect for human dignity.

Linde filed a complaint to Partos, the Dutch association of international development NGOs. But Partos took no action, noting there is no binding agreement for organizations to follow the European code.

After the accusation, the director of Save the Children in the Netherlands at the time, Holke Wierema, defended the ad in an op-ed for Vice Versa, a Dutch-language magazine on global development.

He wrote, "It is unfortunate that the current debate about framing and reframing the totality and diversity of the work of Save the Children is snowed under and narrowed down to the picture that is displayed in a 60-second spot."

Save the Children UK spokeswoman Caroline Anning defends the ad, noting that no complaints were made to relevant UK authorities. "Although we realize that these images may make people uncomfortable, we are committed to showing the reality of the situation and do not shy away from the issues vulnerable children around the world face," she e-mailed NPR in response to our questions about the ad. "This particular advert was one of Save the Children's most successful of all time in the UK in terms of motivating the public to support our work on food crises and chronic malnutrition around the world."

Indeed, it's not always easy to tell when an ad goes too far. At what point does an image become exploitative? What are the dos and don'ts of charity photos in the digital age?

Those questions were discussed this summer at #DevPix, an online chat run by the Overseas Development Institute. ODI is a think tank that works on international and humanitarian issues.

"The general feeling is that development photography has moved on since those classic bad examples," says Pia Dawson, digital editor for ODI. "But despite that, we see every day tons of examples and wonder whether we've really moved on that much. We wanted to take stock and look how far we've come and give a bit more prominence to organizations who are really doing development photography well."

Journalists, academics, photographers, photo researchers and Instagram celebrities tweeted advice about poverty, disaster and humanitarian photography.

They shared recent examples of stereotypical negative photos — what many refer to as "flies in the eyes" imagery:

They also shared what they considered fair and constructive photography, portraying the subjects as self-sufficient and dignified.

But there's a danger of putting too much positive spin on life in poor countries. Brendan Rigby, cofounder of the Australia-based development blog WhyDev, believes some organizations have gone to the opposite end of the spectrum, showing only uplifting images of people in poverty. Like "poverty porn," these upbeat images don't present a full picture, Rigby says.

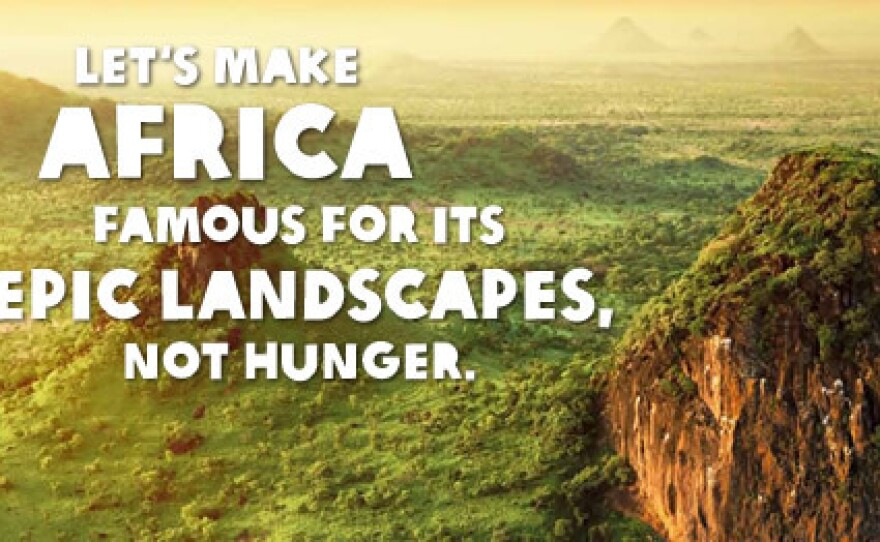

One example of this optimistic approach is Oxfam's Food For All campaign in 2014. The fundraising ads sought to inspire donors with beautiful African landscapes and abundant marketplaces.

"It's no less misleading or unrepresentative of a complicated continent than the previous standard template of war and suffering," says Tolu Ogunlesi, the editor of The Africa Report. "Then again maybe this is me dancing closer and closer to the unanswerable question: What sort of imagery would have been perfectly representative?"

There are some points of agreement: Photographers should get the subject's consent, tell the subject what the image will be used for and provide detailed captions to the organization that will feature the picture. Only then can charities begin to create a more accurate image of countries that many Americans only know through the work of charities and NGOs.

And every day brings new challenges.

"The #DevPix discussion remains relevant because fundraisers always know they can pull on heart-strings as a fundraising tool," says Lentfer. "Look at people's increased engagement in the Syrian refugee crisis after seeing three-year-old drowned Aylan Kurdi."

Lentfer, who authored a set of guidelines for global development communicators in 2014, shared a general rule of thumb: "If that person in a photo was your nephew, your child, your grandmother, would you want them to appear in that ad? If the answer is no, you're over the line."

We want to hear from you. How can members of the public help NGOs and humanitarian organizations fight "poverty porn"? Tell us in a comment below, or tweet your answer using @NPRGlobalHealth and #DevPix.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.