The artist Christo and his late wife Jeanne-Claude are famous for their large-scale environmental artworks. They’ve wrapped entire buildings and bridges in fabric. They hung more than 7,000 panels of saffron-colored fabric throughout Central Park. They’ve spent decades and millions of dollars creating works that are temporary, some lasting just a few weeks.

A new exhibit of Christo’s drawings, collages and sculpture is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego in La Jolla. David Copley, former owner of the San Diego Union-Tribune, who died in 2012, had the largest private collection of Christo works in the United States. Most of that collection is in the museum’s exhibit.

INTERACTIVE: Explore Christo And Jeanne-Claude's Works Around The World

Christo continues to work on two large environmental artworks — one in Abu Dhabi and the other in Colorado — despite the loss of his collaborator and wife, Jeanne-Claude. They started both projects together many years ago and now the 78-year-old Christo is hopeful he will see them through.

On Garlic and Impermanence

Sometimes being a radio reporter comes in handy. Like when you’re doing a story about an internationally renown artist about whom much has been written and you're trying to learn something new.

To get a sound level for my recording, I often ask my subject what they had for breakfast, as I did with Christo on a recent Friday morning. We were sitting in a boardroom at MCASD, with a stunning view of the ocean.

“I had a double espresso, plain yogurt and one head of garlic. Raw garlic,” Christo said. I was unable to mask my surprise, so he said it again for emphasis: “An entire head of garlic. "

The wiry artist eats a head of raw garlic every day. Christo is so convinced of the health benefits, he even travels with his garlic. He packed six heads in his suitcase for his visit to San Diego.

He was here to launch the exhibit at MCASD in La Jolla titled "XTO+J-C: Christo and Jeanne-Claude Featuring Works from the Bequest of David C. Copley."

The show features Christo’s drawings and collages. He does them as preparatory studies for the large environmental artworks done, in the past, in collaboration with Jeanne-Claude. For example, there are studies for “Wrapped Reichstag,” which involved wrapping the Reichstag building in Berlin in fabric.

There are also drawings related to one of their most famous and popular works, 2005’s “The Gates,” when the couple installed 7,503 fabric banners over the walkways of New York’s Central Park.

Christo’s early works are on view too, including drawings of everyday objects like chairs, motorcycles and telephones wrapped in fabric.

Large color photographs of the environmental works mark the beginning of the exhibit. In 50 years, the couple realized 22 projects and failed to get permission for 37. In the '70s, they built “Running Fence,” a 24-mile long fabric fence that wound through the hillsides of Sonoma and Marin counties. In Paris, they wrapped the city’s oldest bridge in fabric. In Australia, they wrapped a coastline with 80-foot cliffs.

These pieces take years to realize. They cost millions of dollars and they are temporary.

“The work exists in that unique moment of reality,” Christo said.

They alter the landscape, shift viewers’ perspectives of it, and then disappear, leaving only the memory of the thing.

“Jeanne-Claude and I love to return to the site of a project,” Christo explained. “We recognize it was a slice of our lives — a part of our lives we can never repeat or get back.”

Just a few years before Jeanne-Claude died, they returned to the coastline of “Wrapped Coast” in Australia. Looking at those 80-foot cliffs they wrapped in fabric, she turned to Christo and said “we must have been nuts.”

Romance and Loss

Jeanne-Claude died suddenly in 2009. The artists were together for more than 50 years.

“Sometimes I think, 'What would Jeanne-Claude say now?'” Christo said. “No one can substitute Jeanne-Claude.”

Theirs is a storied love affair and partnership. They were born on the same day and hour in 1935, he in Bulgaria and she in Casablanca.

They met in Paris, when Christo was a poor painter (he did a portrait of Jeanne-Claude’s mother). He tried to impress Jeanne-Claude by taking her to see an avant-garde play in a tiny Parisian theater.

“The actors were very close and I got us tickets in the first row near the stage,” Christo remembered.

“Jeanne-Claude loved jokes, she loved to laugh. She laughed so much at the play, the actors started to laugh on stage. She was laughing so hard, they stopped the play!” Christo said, laughing himself as he remembered.

When the couple kissed for the first time, it was so passionate Christo broke a tooth.

The Future: "The Matsaba," "Over the River"

Today, Christo is left shepherding the couple's remaining projects to life.

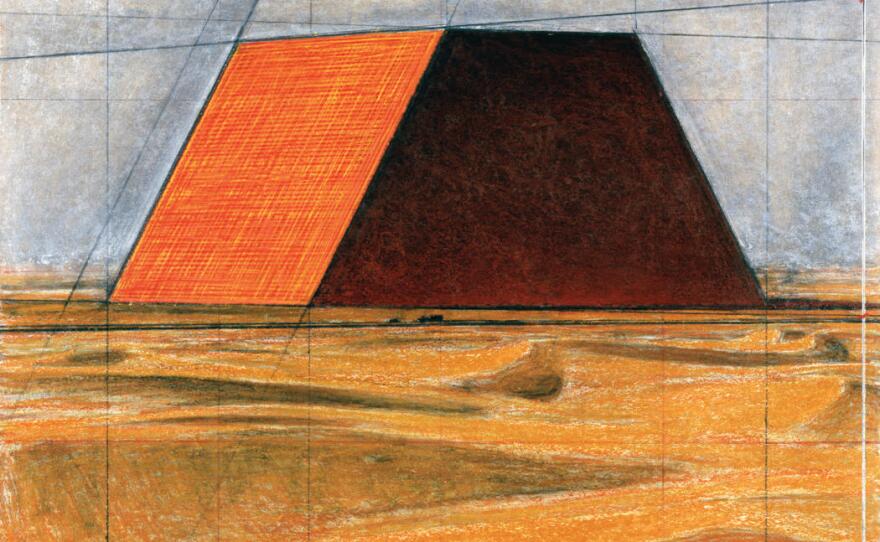

The sculpture in Abu Dhabi is called “ The Mastaba” and will be made from 410,000 brightly colored oil barrels. The couple conceived of it in 1977. If realized, it will be the largest sculpture in the world.

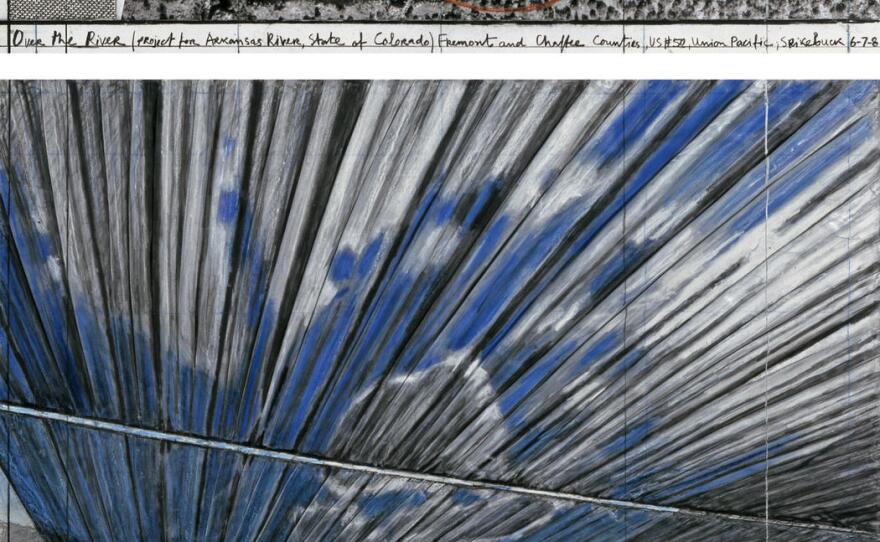

And there’s “Over the River,” a piece that would suspend silver fabric panels in sections above 42 miles of the Arkansas River in Colorado. They’ve been working on this project since the mid-1990s. Each of the environmental artworks takes so long because there’s an extensive permitting process. They also consult with lawyers, engineers, and scientists throughout each planning process.

Christo says there is a software and a hardware period to each of the projects. The software period is “when the work only exists in the drawings, studies, and in the minds of people trying to help, and those that try to stop us,” said Christo. “That software period has energy and participation.”

The hardware period comes after permission is granted and the artist’s team moves to the location of the artwork.

“Jeanne-Claude always says we do this project for us. We like to feel that excitement of getting the project done,” said Christo. “If other people like it, it’s a bonus.”

“Over the River” has been controversial. Opponents say it will impact wildlife, deface the riverbanks, and impede safety and emergency response time. They’ve formed a group called “Rags Over the Arkansas River,” or R.O.A.R.

Construction on the project is on hold due to legal challenges. The Bureau of Land Management approved a permit for “Over the River,” but it’s being appealed. R.O.A.R. has filed lawsuits challenging permit approvals by the BLM and Colorado State Parks.

Christo says he and his team have spent “thousands, millions” of dollars on more than 100 mitigation measures to address environmental impact, wildlife and traffic concerns.

If freed from legal purgatory, “Over the River” will go on view for two weeks in a future summer. It will take three years to build it. According to Christo, much of it will be fabricated offsite.

Christo says the legal challenges and the bureaucracy are as much a part of the artwork as the river and topography. The fabric panels alone, he says, don’t make the art.

He walks me through his vision for traveling underneath the fabric panels by raft.

“Through the fabric, you can see the cloud formations and the contours of the mountains,” he said.

Folds in the fabric will create shadows with the movement of the water. Streams of light will pour through the fabric breaks.

“All of that is the work of art,” Christo said. In other words, he considers the surrounding landscape, the wind, the sun, and the water part of the artwork.

The couple has always financed their projects through the sale of Christo’s drawings and collages to museums and private collectors.

To date, Christo has invested roughly $14 million in “Over the River.” It won’t make any money. None of the large-scale environmental works do. They are, as Christo says, free.

“Nobody can own them. Nobody can buy them. Nobody can buy tickets, nobody can do anything,” the artist said. “And because of that they have this enormous freedom and nobody can possess them.”

He also insists the environmental works have no meaning or content. Their value is purely aesthetic. For him, artwork driven by a message is propaganda.

“Having been born in a communist country, and escaped from a communist country, I am almost allergic to any art that is propaganda,” Christo said. “It can be religious, economic, or environmental propaganda. It’s all propaganda and art is something beyond that.

All the years of work that go into each artwork — research and testing, the legal battles, the bureaucracy, the cost — it’s all for an artwork that is temporary. They are often up for just weeks before they disappear never to be recreated again.

I asked Christo why. He paused and smiled.

“To do work of art,” Christo said. “Basically they exist because they are totally irrational. They are useless. The use of the project is only for the beauty.”

The work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude will be on view at MCASD La Jolla through April 6.