Related stories

For the first time, scientists have been able to follow the spread of an Ebola outbreak, in almost real time, by sequencing the virus' DNA from people in Sierra Leone.

The findings, published Thursday in the journal Science, offer new insights into how the outbreak started in West Africa and how fast the virus is mutating.

A international team of scientists sequenced 99 Ebola genomes, with extremely high accuracy, from 78 people diagnosed with Ebola in Sierra Leone in June.

The Ebola genome is incredibly simple. It has just seven genes. By comparison, we humans have about 20,000 genes.

"In general, these viruses are amazing because they are these tiny things that can do a lot of damage," says the study's lead author, Pardis Sabeti. She's a computational biology at Harvard University.

Hidden inside Ebola's tiny genome, she says, are clues to how the virus spreads between people — and how to stop it.

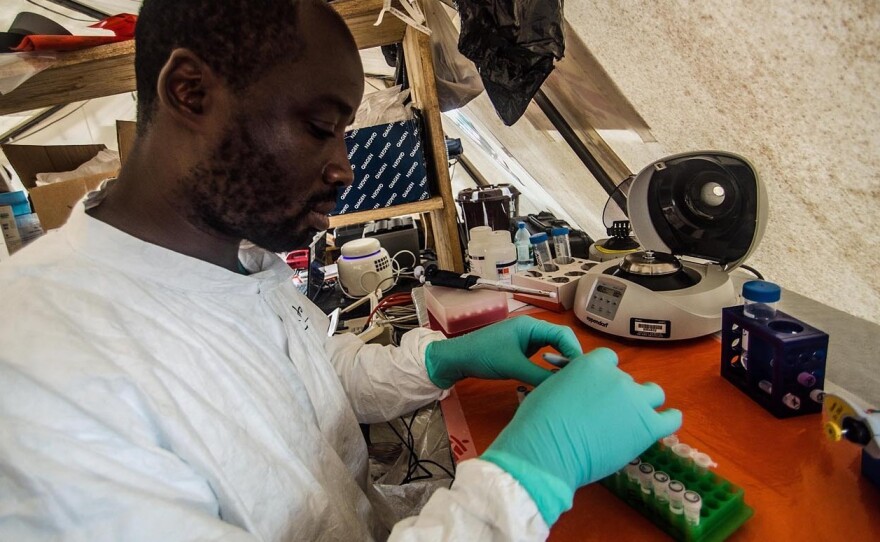

"So as soon as the outbreak happened and was reported in Guinea," she says, "two members of my lab flew out and worked to set up the diagnostics to pick it up in Sierra Leone.

The team helped to find the first Ebola cases in Sierra Leone. They also immediately shipped patient samples back to the U.S. and started sequencing the viruses' genomes.

"We had 20 people in my lab working around the clock," Sabeti says.

The furious work paid off. After just a week or so, the team had decoded gene sequences from 99 Ebola viruses. The data offered a treasure trove of information about the outbreak.

For starters, the data show that the virus is rapidly accumulating new mutations as it spreads through people. "We've found over 250 mutations that are changing in real time as we're watching."

While moving through the human population in West Africa, she says, the virus has been collecting mutations about twice as quickly as did while circulating in animals for the last decade or so.

"The more time you give a virus to mutate and the more human-to-human transmission you see," she says, "the more opportunities you give it to fall upon some [mutation] that could make it more easily transmissible or more pathogenic."

Sabeti says she doesn't know if that's happening yet. But the rapid change in the virus' DNA could weaken the tools we have to detect Ebola or potentially treat patients.

Diagnostic tests, experimental vaccines and drugs for Ebola — like the one used to treat the two American patients — are all based on the virus DNA sequence, Sabeti says. "If the virus is mutating away from the known sequence, that could be important to how these things work."

The new genomic data also indicate that the outbreak started when just one person caught Ebola from an animal. Then the virus has been spreading through human-to-human transmission — not through infected bushmeat, or wild game, as first thought.

"We're really concerned because a lot of the messaging going around ... is don't each bushmeat, don't eat mango, don't anything that might be in contact with animals," she says. "When you see some of those fliers, you're like, 'ok, you just told them not to eat all the man sources of food.' "

So the advice from health officials to avoid bushmeat may be doing more harm than good, she says.

Sabeti and the team also compared the Ebola genomes from Sierra Leone to those found in previous outbreaks in Central Africa. That data suggests the virus has been circulating around West Africa for about decade.

"This study is really an impressive tour de force," says virologist Stephen Morse of Columbia University.

But he's not he's not surprised the virus is mutating so rapidly.

"We seen this in a number of infections, SARS for example, influenza and HIV of course," Morse says. "Very often when a new virus is introduced into the human population very suddenly, it will show accelerated rates of evolution."

So should we be concerned about that the virus might pick up a mutation that makes it more contagious or deadly?

"That's very hard to say. In most cases, the answer would be 'no,' " Morse says. "But Ebola is obviously a concern and very virulent. I'd say it's too early at this point to speculate on what any mutation or any change, even with rapid evolution, might lead to."

A number of scientists working on the project caught Ebola. "Five of them passed from Ebola," Sabeti says, including Dr. Shiek Humarr Khan. He was Sierra Leone's top virologist, who had treated dozens of Ebola patients before catching the virus.

Health workers in Sierra Leone, who talked to NPR in the spring, blamed a lack of proper protective equipment for infections at the government-run hospital in Kenema, where Khan worked.

"The work is just that dangerous," Sabeti say. "Another British nurse at the hospital has just come down with Ebola. You're seeing so many infections going on. It's an extraordinary thing that's going on right now [in Sierra Leone]."

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.