News flash: Whoopie pies are not indigenous Pennsylvania Dutch food, no matter what the tourist traps say. Nor are the seafood bisque, chili, roast beef, and other dishes crowding the steam tables at tourist restaurants in Lancaster County, Pa.

Instead, how about some gumbis, a casserole of shredded cabbage, meat, dried fruit and onions? Or some gribble, bits of toasted pasta akin to couscous? Or some schnitz-un-gnepp: stewed dried apples, ham hocks, and dumplings?

All are iconic Pennsylvania Dutch fare, according to William Woys Weaver, author of a new tome on Pennsylvania Dutch food, "As American As Shoofly Pie."

The book's subtitle, "The Foodlore and Fakelore of Pennsylvania Dutch Cuisine," suggests that Weaver, who grew up with a grandfather who spoke to him only in the dialect Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch, is not taking a wholly reverent look at his native cuisine.

Indeed, Weaver seems to have had a ripping good time unmasking the fake Pennsylvania Dutch tourist culture, with its hex signs (bogus) and windmiills (faux) and buffets designed to fill up busloads of tourists on a budget.

Funnel cakes, considered by many to be echt Pennsylvania Dutch, were a rare holiday treat until they were popularized as a fund-raiser at the Kutztown Folk Festival in the 1950s, Weaver says.

Well, so much for tradition.

At the same time, Weaver has taken seriously his mission to rediscover the foods of his ancestors, interviewing hundreds of people over 30 years. A food historian, he directs the new Keystone Center for the Study of Regional Foods and Food Tourism.

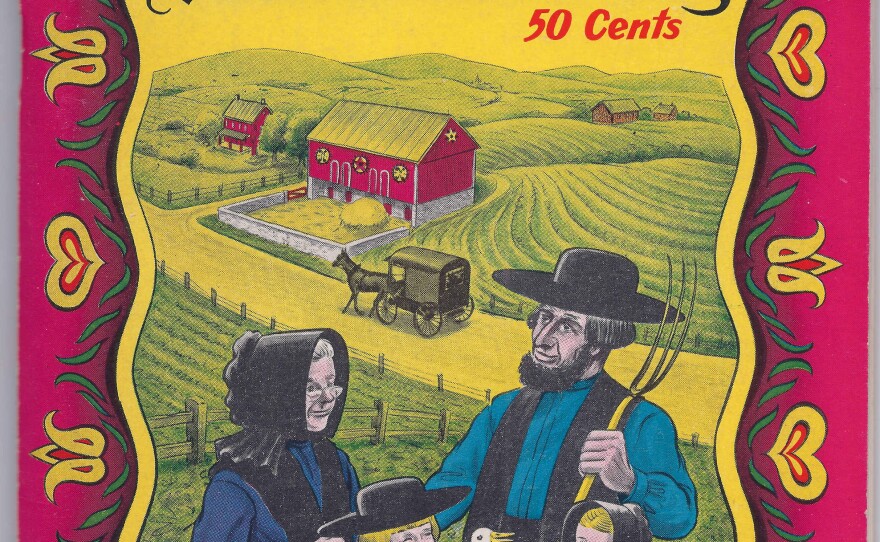

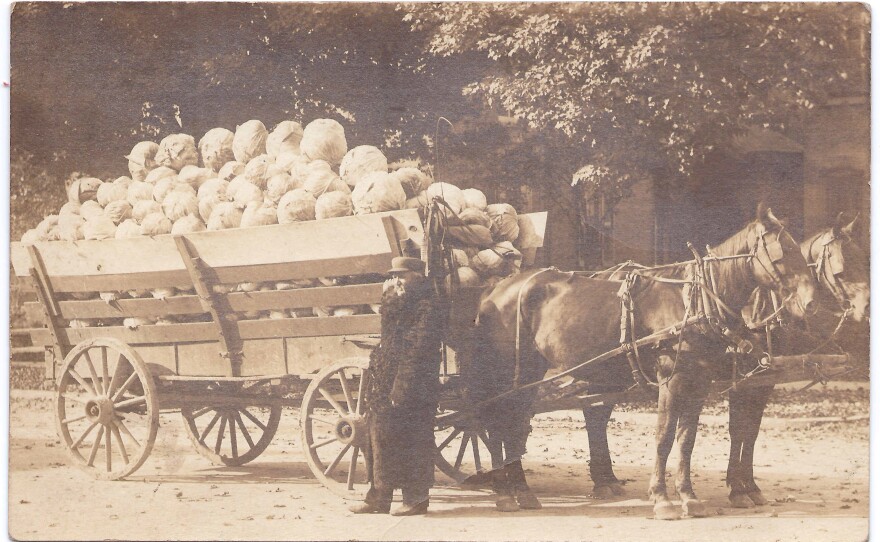

Pennsylvania Dutch, he notes, isn't a synonym for Amish. Instead, it's the culture of people who came from Germany and Switzerland in the 17th and 18th centuries and settled in southeastern and south central Pennsylvania.

Some were Lutherans, some Anabaptists, some Mennonites. Some were rich enough to eat hasenpfeffer, rabbit braised in wine. Some were "buckwheat Dutch," so poor they ate rarely ate meat, and got by on "hairy" dumplings, made with shredded potatoes that stuck out when the dumplings were boiled.

"Because they were poor, they had to be creative," Weaver says. "They were eating ramps. They were eating wild asparagus. They were eating huckleberries. Of course, the Victorians wanted everything in white sauce, and looked down their noses at [that food]. But we can see it as something very close to the land."

That authenticity, Weaver says, is something that can be used to create a "new Dutch cuisine." He's talking to chefs in Pennsylvania about incorporating traditional Pennsylvania Dutch dishes into their menus. "There's good stuff out there," he says, "it just needs to be uncovered."

The recipes in the book should help; they include familiar-sounding fare like Punxsutawney spice cookies, and surprises like peach and new potato stew.

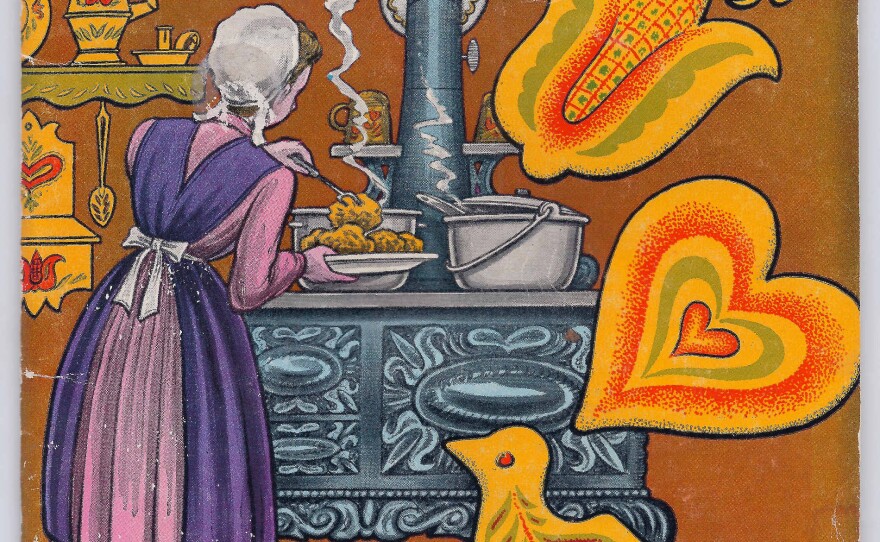

Then there are the one-pot dishes, like that gumbis. It was a frugal meal that could be cooked on a hearth or a stove. It wasn't rare for rural families to eat it without plates or silverware, Weaver says, by dipping chunks of bread in the communal pot.

"They're sort of fun for people who want to sit around and pick at things out of the pot," Weaver says. "We even have a word for eating that way. We call it schlappichdunkes -- messy gravy."

Copyright 2013 NPR. To see more, visit www.npr.org.