Noir reading list

June: "Fallen Angel" by Marty {Mary} Holland

July: "The Postman Always Rings Twice" by James M. Cain

August: "Build My Gallows High" (filmed as "Out of the Past") by Geoffrey Homes

September: "Pitfall" by Jay Dratler

October: "Gun Crazy: The Birth of Outlaw Cinema" by Eddie Muller

November: "The Big Heat" by William McGivern

December: "Badge of Evil" (filmed as "Touch of Evil") by Whit Masterson

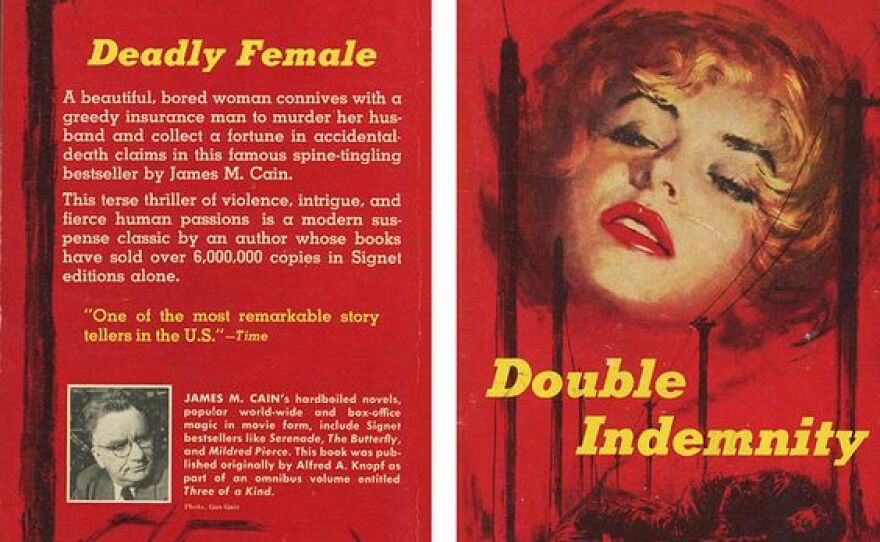

Guest blogger D.A. Kolodenko looks to James M. Cain’s “Double Indemnity” and the film adaptation by Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler for the May Noir Book of the Month Club.

This one comes to you from The Stardust Motel in Palm Springs, California, where I’ve been emerging daily from the darkness of the Arthur Lyons Palm Springs Film Noir Festival into the blazing sunshine — a contrast as stark as the photography that gives so many noir films their expressionistic, moody quality. In its 18th year, it’s my favorite of the Film Noir Foundation fests. You should come out here next May because in a single weekend you can see a dozen films — often rarities courtesy of major studio archives — and spend the rest of the time pretending you’re William Holden at the beginning of “Sunset Boulevard.”

Not a bad place to write about “Double Indemnity,” the book adapted for the first of our two May films in the ongoing Noir on the Boulevard series.

James M. Cain’s 1943 novel is an oasis of artful, stylistic, suspenseful, funny entertainment that is also as heated and bleak as the desert. The screenplay of the 1944 film version was co-written by director Billy Wilder and crime fiction writer Raymond Chandler, whose novel “Farewell My Lovely” was also adapted for the screen in 1944 as “Murder My Sweet,” the second film in our May double feature. I’ll be writing about the latter in my next blog entry, but the focus here is on “Double Indemnity.”

If you were asked to name just one classic film noir, you’d be likely to name this one. At or near the top of everyone’s 10 best list, it’s probably the most beloved, satirizedand analyzed noir. Its plot, theme, setting, performances, dialogue, cinematography and mise en scene have become a template of a specific kind of noir that might be the most noir kind of noir: a scoundrel of a guy falls for a bored, depraved wife and helps her deal with a husband problem.

Spoiler alert: everything goes to hell.

But as iconic a film as it is, most people who’ve seen the movie haven’t read the story, which is a shame. I’m here to tell you that this is the first truly noir read so far in the series, and if you were to only read one — though of course you’re reading them all — make it this one. I reread it for our series over the course of a few train commutes — it pulls you in and doesn’t let go. There will be spoilers in this post, so if you haven’t read the book yet or seen the film, return after doing so.

Cain’s inspiration

Cain wrote “Double Indemnity” in the voice of a scoundrel named Walter Huff (changed to Neff for the film), an insurance salesman who knows the value of a policy but not of a life. This first-person voice is a chief success of “Double Indemnity” and of Cain’s other early novels. He had a talent for getting down on paper the way everyday folks sounded.

It is, in fact, just what he set out to do: “I tried to write as people talk,” he said in a 1977 interview in The Paris Review. Having been raised in a strict household with parents obsessed with the way people should talk, Cain in that same interview said that he “even as a boy, was fascinated by the way people do talk.”

Cain so convincingly captures the nuances of everyday speech in his tightly crafted sentences that the prose rarely seems overly colloquial or forced.

The story itself was based on a high-profile murder he had reported on as a New York newspaper journalist.

“The Postman Also Rings Twice,” his prior celebrated love/murder triangle novel, was based on the same events. In 1927 housewife Ruth Snyder took out a double indemnity insurance policy on her husband, conspired with her boyfriend to kill him, and became famous as the first woman sent to die in the electric chair in the U.S. since the 18th Century.

“Double Indemnity” was first published in novel form — or novella, if you don’t think 134 pages counts as a novel — in 1943, but it originally appeared as an eight-part serial in Liberty magazine in 1936 — thus its unbridled depression-era pessimism. And unlike most 1943 crime dramas, the bad guys aren’t Nazis but rather the internal, psychological demons of and the story’s shockingly murderous femme fatale, former nurse Phyllis Nirdlinger (changed to Dietrichson by director Billy Wilder to make the name less distractingly goofy).

Phyllis is a retired nurse married to a moderately wealthy oil pioneer who works on wells in Long Beach. Walter encounters her when he stops by their Hollywoodland Spanish revival home to renew the husband’s car insurance policy. When the alluring Phyllis casually asks about purchasing accident insurance for her husband, Walter immediately knows what she’s on about and drops her flat — but of what use is it in the noir universe to try avoiding the web of a black widow?

Femme and homme fatale

What the film leaves out is that Walter is no mere fall guy. He admits to the reader that he’s nuts, but not just for going along with Phyllis’s plan to kill her husband. After 15 years of exposure to insurance-fraud-murder-scams, he’s been lying awake at night thinking up tricks, so he’ll be ready for them when they come at him. By the time he meets Phyllis, he’s already thought up the perfect trick and knows he could pull it off if he had a plant — Phyllis is that plant, he confesses to the reader.

This is something you don’t get from the film — Walter is attracted to Phyllis as much for her “set-up” as for the figure under her blue silk pajamas. In the novel, femme fatale meets homme fatale, and they commit a murder together they’ve already separately been planning.

Regardless of this theme of dual complicity, Walter (played by Fred MacMurray in the film) is the pathetic center of this story and is somewhat redeemed for his ultimate effort to protect Phyllis’s 19 year-old stepdaughter, Lola. His feelings for her are like a “sweet peace” in contrast with his “unhealthy excitement” for Phyllis (played by Barbara Stanwyck). That’s where Cain’s novel most fulfills the era’s patriarchal narrative expectations, even more so than in following the unwavering convention that the femme fatale must be punished for her transgressions.

The claims man Keyes (played so effectively in the film by Edward G. Robinson) is the patriarchal enforcer, onto her from the get go. While the film builds suspense around Keyes’ determined investigation, in the novel, he’s immediately convinced it was an attempt to commit the perfect murder, and suspects Phyllis. To avoid Keyes’ suspicion, and moreover his post-murder revulsion and transference of guilt onto Phyllis, Walter tells her he must stay away from her, even though he loves her. But he admits to the reader that he “loved her like a rabbit loves a rattlesnake.” The novel’s suspense in the third act is built more around when and how the snake bites — for there can be zero indemnity in noir when the loss or damage is of human life.

Phyllis Nirdlinger: a vision of death incarnate

It is ironically in the creation of this snake, Phyllis Nirdlinger, that Cain transcends the typical wicked woman archetype. Phyllis is the most remarkable femme fatale in 20th century literature, the depth of which the film’s surface barely scratches.

Even as Stanwyck so compellingly reveals Dietrichson’s depravity, it can never go where the novel goes. Phyllis is a mentally psychotic serial killer who has committed nine previous murders as a nurse, including the killing of three children. Sometimes she horrifies herself and is overcome with bouts of regret, but more often she imagines herself as death incarnate in a scarlet cloak, bringing peace to those who just don’t understand that they’ll be happier dead. Lola describes to Walter the time she caught Phyllis, wrapped in a red silk shroud, her face coated with white powder and red lipstick, brandishing a dagger, making twisted faces at herself in the mirror. Phyllis never loved Walter, she even tells him so in the film.

But only the novel reveals that “death is her bridegroom, the only one she ever loved.”

In the penultimate year before its 75th anniversary, the film endures as the ultimate noir, and it certainly holds up, but the novel is just far darker and weirder and more fascinating. Compare, for example, the very different endings, and let me know what you think.

A couple side notes

A familiarity with Chandler’s style can help you recognize, to an extent, what he brought to the screenplay of “Double Indemnity.” Clearly, the film’s well-known double-entendre-laden dialogue between Walter and Phyllis is a Chandlerian addition. But what did it really add? That sort of dialogue is better suited to a hardboiled character like Chandler’s idealized tough-guy detective Phillip Marlowe, whom you meet in “Murder My Sweet,” than a semi-articulate dim-wit like Walter, whose only game is in gambling with human lives.

But it does make for fun cinema.

Last thing for now: I’m a collector of appearances or mentions of San Diego in classic noir literature and film (stay tuned for details about a presentation of prominent cinematic examples that Beth Accomando and I will be presenting this August at the La Jolla Athenaeum Music & Arts Library), and our mythically sleepy, military border town does get a mention in “Double Indemnity.” Walter, disguised as the injured Mr. Nirdlinger, encounters a man on the train’s observation platform who recounts a story about “an experience [he] had with his wife, coming home from San Diego.” Walter doesn’t share the story with us — it’s beside the point of this random guy’s potential interference with the murder plot — but it’s meant to illustrate how “women are funny”, particularly when it comes to driving.

The irony of course is that Phyllis is hardly the amusing little helpless wife who can barely handle a car — at that very moment she’s transporting her murdered husband’s corpse to the rendezvous point for the staged accident. San Diego here is just some not-too-distant mundanity to be left behind, as it’s figured so often in the Los Angeles-centric noir universe.

D.A. Kolodenko: Musician. Waiter. Warehouse worker. Print shop manager. College professor. Lecturer. Columnist. Journalist. Editor. Science writer. Advertising copywriter. These are some of the things I’ve been. Detective. Hitman. Embezzler. Boxer. Prison inmate. Fugitive who escapes by running into a tunnel or climbing up something. These are some of the things that the books and movies I like have taught me to avoid being.