Nearly half of California college students have to revisit some high school material during their freshman year. The Center for American Progress estimates it costs them more than $200 million dollars in repeat coursework.

Colleges recently announced changes to tackle the problem on their end. The Sweetwater Union High School District is looking for solutions at the high-school level.

RELATED: Cuyamaca College Offers Case Study In Eliminating The ‘Math Pipeline Of Doom’

It has partnered with San Diego State University’s Center for Research in Mathematics and Science Education to pilot a new course for seniors. It is one of five groups participating in the federally funded California Mathematics Readiness Challenge Initiative.

“We’ve had, for quite awhile, a large number of students and a large amount of money being invested in developmental math at the community college and (California State University) levels,” said SDSU researcher Osvaldo Soto, the principal investigator on the project. “So how can we get students interested in mathematics, keep them interested in the pipeline, but at the same time figure out what’s going on.”

Enter discrete math. Sweetwater teachers worked with Soto and his team last year to develop curriculum around things like game theory and cryptography, or decoding secret messages. Students are now in their eighth week and are wrapping up the lesson on games.

“I like it here in discrete because it’s much simpler — it’s much more about how we got the answer, but not about the way to get to the answer,” said Otay Ranch High School senior Jarrad Holguin.

The course focuses more on the “why” than the “ how,” moving away from equations and spending most of class time exploring concepts.

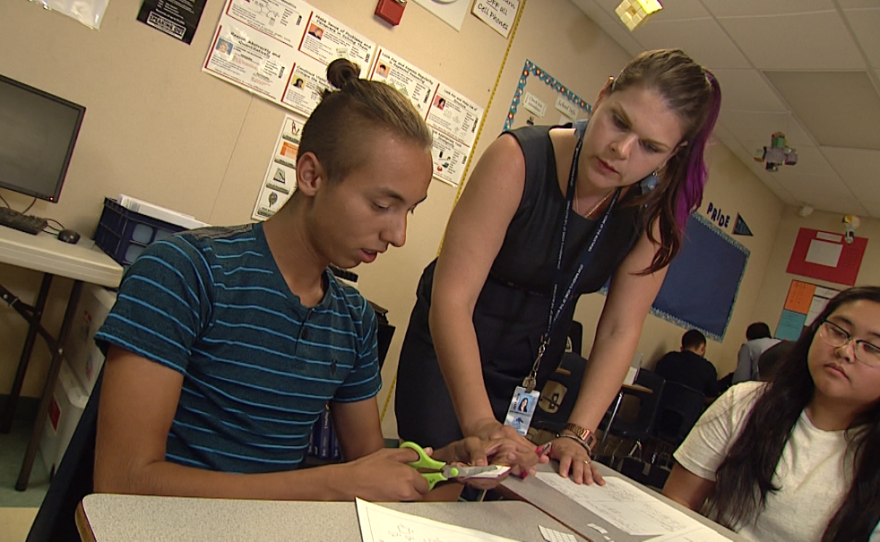

“It’s kind of how mathematics works behind the scenes,” said Otay Ranch teacher Nicole Meyer-Sandez. “The students are collaborating together, they are strategizing, they’re solving puzzles, they’re trying to prove what they have come up with in their answer in a way that nobody will doubt.”

During a recent class the students developed their own games using blocks and tokens, then used math to understand which strategies would work best in the games. The hope is that this new take on high school math will improve understanding so students are more likely to retain their skills and remain interested in the subject.

“We’re really trying to create students who can think critically,” said Otay Ranch teacher Anne Marie Almaraz. “I am not interested in creating a student who can read back to me what I just said. That, to me, is not worth much.”

Almaraz and Meyer-Sandez co-teach two discrete math classes, allowing them to give students more individualized attention and support one another in the new course.

The group will share its results with the state and post its curriculum online for other schools to implement. Other pilots are running in Salinas, Sacramento, Palm Springs and Lawndale.

Last month the California State University announced its campuses would significantly cut down on the number of non-credit-bearing remedial courses they offer, instead working remediation into college-level courses or offering accelerated, credit-bearing remedial courses. Community colleges, too, have been making changes.

Researchers have found students, especially those from traditionally disenfranchised groups, often get stuck in remedial classes and are more likely to drop out. One San Diego educator has described it as “the math pipeline of doom.”

“I think somewhere along the way when algebra was introduced, they kind of lost the love of math because it started to get a little more challenging and more abstract,” Meyer-Sandez said. “I think this idea that we’ve brought in with the discrete math course and having the students working together and lead discussions has really brought back that desire to know the math, and learn the math and actually love it a little bit more than they have.”