One of the clearest ways to give a child a leg up is to be involved in his or her education. But what if you can't read homework assignments or call the teacher? That is the reality for more than 400,000 San Diego County adults whom the U.S. Census has identified as struggling to speak English.

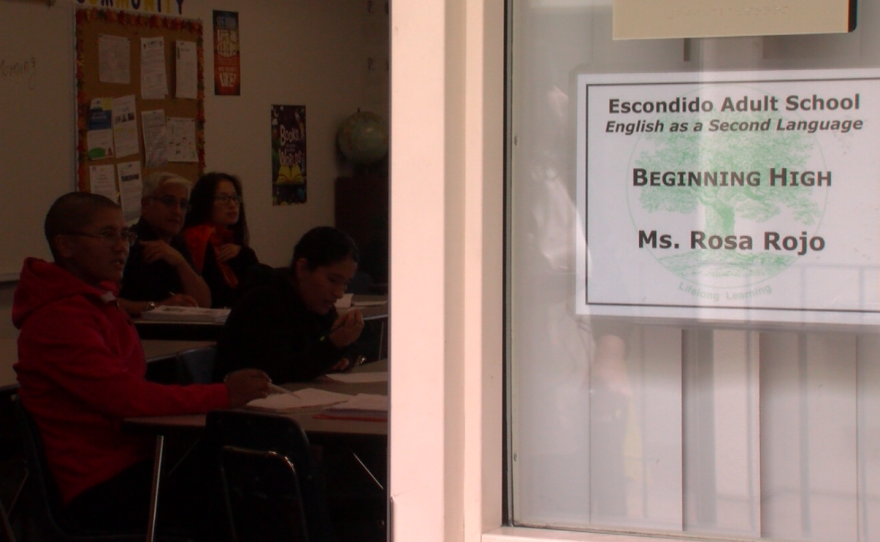

Anamaria Hernandez was one of them before enrolling in Escondido Adult School.

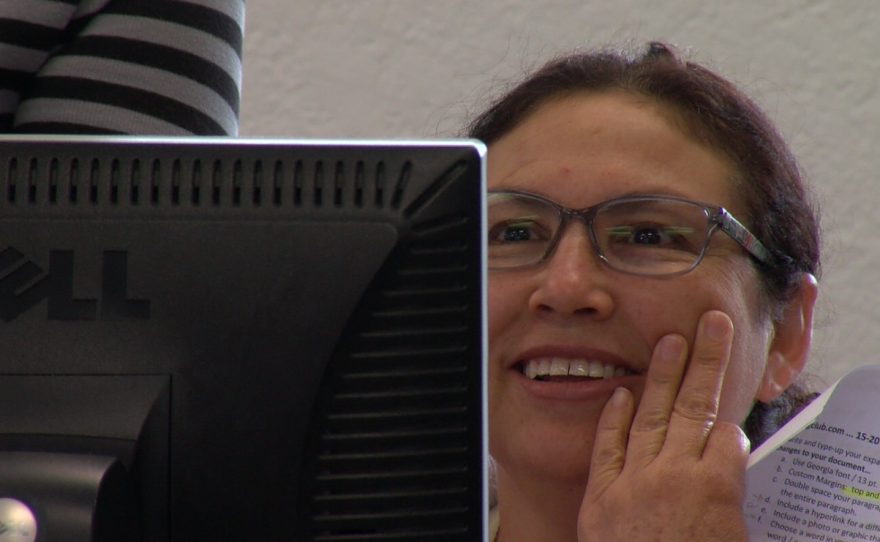

"I always want to learn English because I feel embarrassed when I'm speaking with a native (speaker). I feel like they think I'm stupid — I'm sorry for that word," Hernandez said. "I'm not. It's because I didn't know how to communicate."

The 52-year-old is now in an advanced English class, where she is also picking up basic computer skills. She said she is excited to put them to work in emails to her son's teacher. That kind of communication did not come as easily when her older children were in school.

"I know they (felt) embarrassed," Hernandez said. "They were embarrassed, because when I had to go to the meeting with the teacher, after they would say, 'You should know how to speak.'"

That desire to better advocate for their children is what drives many to enroll in English-language courses. Demand is increasing across the county and in Escondido, especially among parents at its elementary schools.

But new federal guidelines passed under the Obama administration could make it harder for adult schools to provide classes for parents like Hernandez. The rules, which are not expected to change anytime soon under President Donald Trump, shift the focus of adult education from enrichment to job placement.

"The challenge for us is not all of our English-as-a-second-language students are coming here necessarily for employment," said Dom Gagliardi, principal of Escondido Adult School. "They're here to improve their English skills so they can be more successful working with their own children, improving those communication skills to work with their teachers."

Under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, adult schools will need to show an increasing number of students are using their programs to catapult into jobs or higher education. Currently, they just need to show their ESL students improved on a posttest or went on to earn U.S. citizenship or a GED.

"I understand it to some degree because these are federal dollars and we want to show they're effective, but I think there's a certain blindness to the fact that not everyone is looking for a job," Gagliardi said. "It's a little bit myopic."

Gagliardi said some of his students are already retired. And he said there is long-term value in helping parents help their children. Research has long associated parent involvement with gains in math and reading, and decreases in problem behavior.

The new focus on jobs could make such students a liability. While the rules are not yet finalized, they are expected to tie a portion of funding to how many students enroll into new jobs, career-technical training or college.

Gagliardi said if schools lose funding, they might have to separate out students who are not looking for jobs and make them pay for their lessons. Currently, the classes are free due to federal subsidies. Gagliardi said it is unclear whether schools could actually make that change under the law as written.

"Like anything else that's new, there's going to be a transition year. I think for the time being everything will stay as is and then we'll see what the data looks like," Gagliardi said. "We are concerned what that data will look like."

Andrew Picard is director of programs for San Diego Workforce Partnership, which administers the federal dollars locally and manages job training and placement programs. He said those concerns are valid.

"Adult ed works with some of the hardest-to-serve demographics," Picard said. "They work with immigrants who have very limited English skills, or maybe refugees. And while maintaining employment is critical for success, that might not be their first priority. Their first priority may be housing or food."

But Picard said the focus on job placement does have an upside. There currently are not enough skilled workers to staff the region’s growing industries.

"We see that there are skills gaps," he said. "San Diego attracts a lot of talent. We're one of the biggest applicants for H-1B visas, so people who are coming from overseas. We'd really like to grow more homegrown talent here in San Diego."

The changes in federal workforce funding, coupled with a shift in state funding five years ago, have also spurred more cooperation among schools and service providers. Picard said that is a good thing.

"There's never enough funding and never enough program services to meet the needs of our community," he said. "So I see this stronger focus on partnering together, aligning our performance, creating a symbiotic relationship that allows our funding to go further."

RELATED: Proposed Cuts Would Impact San Diego Job Training Programs That Are Booming

He said local agencies are now in a good position to tackle another big challenge under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act: collecting data. Adult schools traditionally have not tracked their students once they leave their programs. Now they will need to update their employment status after several months.

As for Anamaria Hernandez, she will likely score Escondido Adult School some points under the new rubric. She's hoping to obtain her GED and eventually leave her job as a night custodian to become an accountant.

But she is already achieved something big that will not count.

"When (my kids) hear me talking with somebody they say, ‘Good job mom, you are speaking very good now, I'm so proud of you.’"

Adult school administrators will find out next fiscal year how large a role job placement plays in their funding. They just hope there is some recognition that simply closing the language gap for one generation could close the achievement gap for another.