I’m not friends with Christopher Cabaldon. He’s the mayor of West Sacramento and I’m a journalist who covers city politics. We’re more like fencing partners. I’ve reported on the mayor’s efforts to grow the local economy and to finance a downtown streetcar.

But when I published an essay last year about being involved in a violent accident that killed my mom, the mayor texted me to say when he was 12, he was sitting beside his mother Diane when she died in a car accident. The next time I saw Cabaldon, I pitched him on the idea of a magazine article to tell his story. As it turned out, the mayor is a public figure with a very private life. At first, he wanted to keep it that way.

“Well I didn’t want to do it. Who would want to do this?” Cabaldon later recalled. “There is no part of me that wants to talk to other people about [my mother’s accident]. And you’re a reporter. I’ve sparred with you plenty of times in our respective roles.”

Eventually the mayor trusted me to write the story because he believed my similar experience would allow me to approach the assignment with honesty and sensitivity.

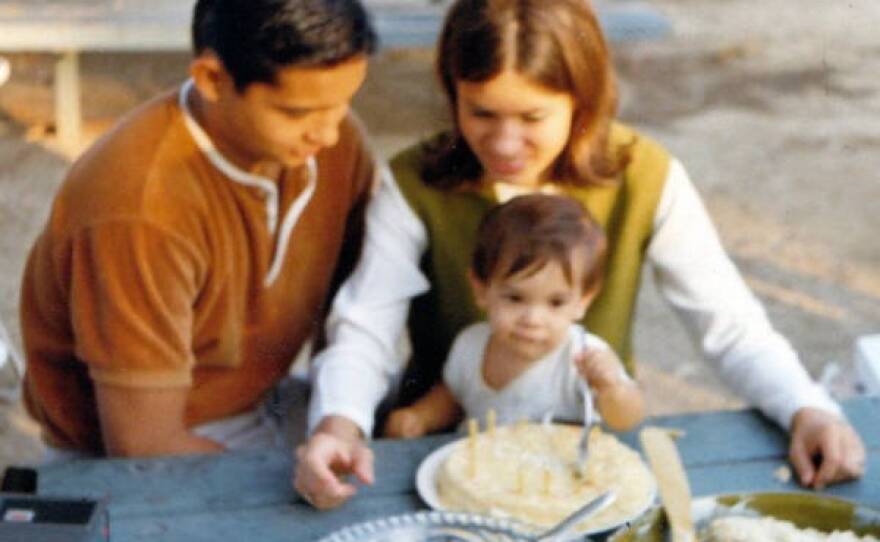

At the time of her death, Diane was divorcing Cabaldon’s father, Larry. The accident occurred on a Friday night in April, 1978. Diane had brought Cabaldon to her sister’s house for a birthday celebration. Diane danced, she drank, and at the end of the night she headed home with her two sons in the backseat.

Diane slammed her BMW into a guard rail driving the wrong way up an off-ramp in Los Angeles. Cabaldon remembers falling asleep in the car and then waking up covered in bandages in a hospital room.

“My dad comes in the room and says, ‘Boys, there was an accident. You were in a car accident and your mom didn’t make it,'” Cabaldon said. “All at once, she was gone.”

I can relate to that moment, that moment you realize you are having the worst day of your life. My mother’s accident occurred on Christmas day, 2008. I was 24 and home in Petaluma for a long weekend. My mom, Sydney Parks, was divorced and I was her only child.

We woke up early to drive to the Sierra Mountains to go skiing. But this big blizzard kept us in traffic for hours, and when we finally arrived at the ski resort, the conditions were so bad we just decided to go home.

I started to get frustrated, but my mom, Sydney Parks, said “Relax your brow.” That was her phrase whenever she caught me being sad or brooding. She’d say those words and softly wipe her hand across my forehead.

On the way home, we decide to go for a hike. We were walking away from the car on what looked like a perfect trail, with a hill on one side and a creek on the other. I looked down and realized we were walking on train tracks. Mom was ahead of me, and I assumed since most businesses were closed on Christmas Day, a train would not roll through.

We had made it a couple hundred feet on the tracks when a big plow train sped around a curve. We hadn’t heard a thing until it was right in front of us, charging at us. The train had this huge metal grille, and waves of snow were spewing out of it from both sides. A yellow spotlight at the helm resembled a big eyeball. We started running and my mom fell in the middle of the tracks. I turned around and grabbed under both her armpits, and I tried to throw her out of the direction of the train. As I lifted her up, we were both struck.

I was knocked a few feet from the train and landed face first in the snow. My mom was hit head on by the train and thrown about 25 feet. As the train screeched to a stop I was thinking, “I need to get to mom.” I tried to lift myself up, but my right arm, and my right foot, were both broken and could not take any weight. I slid across the snow with my left arm and leg. When I reached mom, she was slowly blinking her eyes and opening and closing her mouth. She made no sound. Parts of skin on her lips had been torn off, exposing teeth. My thought was, “This is really bad.”

I just start repeating the same words over and over again. ‘We’re going to be OK. Don’t worry. We’re going to be OK.”

By the time the paramedics get there, mom had stopped moving. A team of guys hoisted me onto a plank and started walking me toward the ambulance. And that’s when I lost it. I just started screaming.

When a parent dies, you’re left with a memory and whatever advice you can hold onto. West Sacramento Mayor Christopher Cabaldon told me his mother Diane remains the most important person in his life, and with everything he does, he just wants to make her proud. He regularly drives to Los Angeles to visit her. He stands over her grave and talks to her, out loud.

Even though she died when he was 12, Cabaldon can still imagine what advice she would have for him today.

“You don’t need the person there to actually give you a sense of love,” Cabaldon said. “Just the idea that she’s still with me in some way, whether she is watching over me or just in my own heart, that gives me a sense of strength.”

After I publish the mayor’s story, he and I return to being fencing partners. But my interview with him made me realize that I should be more conscious about my ongoing relationship with my mom.

Mom, I want to speak to you directly. I still get stressed. I get frustrated. Your phrase — “relax your brow” — it still means a lot. I can feel you reach out and touch my forehead.

“Don’t worry,” you tell me. “We’re going to be OK.”