Footsteps from the U.S.-Mexico border, Janeth Aguilar sat on the trash-strewn, dirt-browned sidewalk of Tijuana, exchanging kisses with two Haitian children.

“I love them, they love me,” she said.

She pulled oatmeal bars from her purse and gave them to the children.

“We come to give them a happy moment,” she said. “Since they lack everything, we want to make sure they don’t lack a smile.”

Aguilar, a 36-year-old Mexican woman, is one of a rising number of Tijuana residents responding with unusual hospitality to a surge of Haitians and Africans on their way to the U.S. They bring clothes, snacks, sports drinks. They prepare full meals. They pick the travelers up off the streets where they sleep, offering beds in their houses.

A backlog at the ports of entry means thousands are stuck in limbo in Tijuana, waiting to speak to a U.S. immigration official. This week, the U.S. government announced it was going to start sending many of the Haitian newcomers back to Haiti. Others who come from various African countries, fleeing terrorist groups, will be processed as usual.

Since the influx started in May, thousands of Haitians have entered the U.S. with a notice to appear in immigration court, thanks to protections they received after the devastating 2010 earthquake.

Not anymore. Now, Haitians who present themselves at the ports of entry will be placed in detention centers and sent home unless they prove they fear returning.

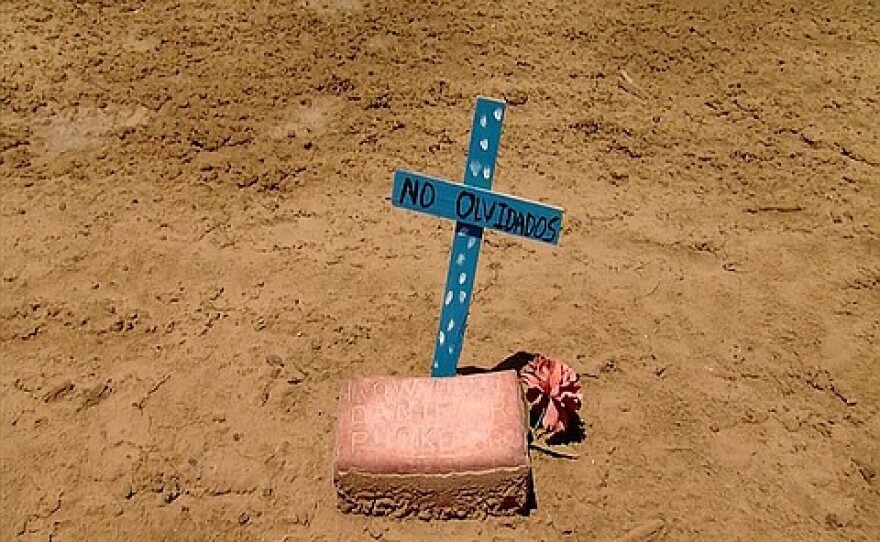

But tens of thousands are still on their way, journeying north through the jungles and mountains of Latin America, battling hunger, dodging criminal groups, enduring exploitation. Some are raped. Others are killed – all with the hope of making it to the U.S. They come from Brazil, where thousands had moved after the earthquake.

Most planned to cross through the San Ysidro Port of Entry, then fly to Florida, where some of their relatives live.

What they will do now remains to be seen. In the meantime, Tijuana residents are taking care of those who have come.

“We Come Every Day”

Aguilar remembers the first time she saw the large crowds of Haitians and Africans on the streets of Tijuana. It was unusual – less than one percent of Mexico’s population is black, and the north is even whiter than the rest.

She went online to find out what was happening. She learned the migrants were coming from countries with political and economic crises. She wanted to help.

“They’re really lovely people who need our help during their difficult situation,” Aguilar said. “We come every day. We bring them candy, food, we’re with them a little while. Yesterday, they braided my whole head of hair.”

How does she communicate with them, since she doesn’t speak French or Creole or Portuguese?

“Just with smiles and hand gestures, they give me a kiss or sit in my lap,” Aguilar explained.

Tijuana, as a border city, has a long history with migrants en route to the U.S. – mostly from southern Mexico and Central America. Those migrants, including those deported from the U.S., are often shunned by the locals, forced to live out of sight, in sewers.

Last year, the Tijuana mayor ordered the removal of hundreds of those migrants off the streets, locking them away in controversial drug rehabilitation centers, including those who weren’t using drugs. Tijuana residents interviewed by KPBS expressed relief, saying the migrants had become an eyesore.

In stark contrast, Mexican officials have been receiving the Haitians and Africans with open arms, offering documents that give them formal permission to be in the country while they wait their turn to appear before U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

"You're Mexican, What Do You Lack?"

On a recent Monday, Tijuana residents set up a table on the street in front of Desayunador Salesiano, Tijuana’s largest migrant shelter, where hundreds of the Haitians and Africans sleep.

The residents handed out plates of fried chicken, rice and beans. Some of the southern Mexican and Central American migrants who also live on the street squeezed into the lines for food. Jorge Cruz, a 39-year-old Tijuana taxi driver who brought the chicken, was not happy about that. He confronted one of them.

“I told him, you’re Mexican, what do you lack?” he said.

Some of the Mexican and Central American migrants are also fleeing dire circumstances such as persecution and hunger. But locals have an easier time perceiving the Haitian and African migrants as needing their help.

“Even In Their Situation, They’re Happy”

Cruz said the Haitians and Africans inspire him.

“Even in their situation, they’re happy,” he said. “They smile.”

At first, Tijuana residents brought the Haitians and Africans things like tacos and burritos – Mexican food. But they didn’t like it. The residents investigated, and learned that the visitors preferred simple things like chicken and rice. They brought that instead.

“We just found out that they like whole beans, not crushed beans,” said Jose Luis Aguilar, who set up the table with funds from his church, Nueva Generación de Jesus.

The next morning, the dining room at the migrant shelter across the street, Desayunador Salesiano, was empty of Haitians and Africans. They weren’t interested in the shelter’s chilaquiles, a staple Mexican breakfast – they had other options outside.

“An Alarming Crisis”

Margarita Andonaegui, a coordinator at the shelter, said Desayunador Salesiano has been struggling to feed and house thousands of Haitian and African migrants. Her shelter is one of five in Tijuana that have been addressing the surge, funded by donations.

“We feel suffocated,” she said.

But Andonaegui said generous residents are actually making the situation worse.

“This is turning into chaos, into an alarming crisis,” she said.

All the charity has created a sort of party atmosphere in the street, she said. People leave trash everywhere. Migrants fail to come into the shelter for planned community activities such as silent films and educational workshops. Their children get sick from all the sugar and candy. Haitians and Africans are mixing with homeless Mexicans who use drugs, she said.

“They’re addicts who take advantage of the situation, and they say, ‘my Haitian friend, I love you, smoke this, drink this,’” she said.

She said previously well-behaved Haitians and Africans are showing up under the influence. The shelter won’t let them in.

Andonaegui said she’s also worried about all the drivers who keep stopping to pick up the migrants, offering temporary housing and in some cases jobs. She took a picture of one truck as it passed. The bed of the truck carried about a dozen of them.

“Where did it take them? What was the purpose of taking them? They don’t know what problem they’re getting into,” she said.

The shelters are working with immigration officials to slowly funnel the migrants to the ports of entry. Once in San Diego, the United Methodist Christ Ministry Center was giving them temporary shelter on their way to Florida. But now that the U.S. has decided to start sending Haitian newcomers back to Haiti, everything is going to change, Andonaegui said.

Many of the Haitians may decide not to cross into the U.S. at all – because they don’t want to go back to Haiti, where the economic situation is even more dire than in Brazil, where they were living before coming to the U.S. border.

“If you’re going to cross into a country where they’re going to take you to where you don’t want to go, which is Haiti, then you’re going to find an alternative,” she said.

In this case, she said, the alternative could be Tijuana.