Nine months after they bought the apartment buildings at 2605 Logan Ave., LWP Group threw a party.

The leaks, mold and relentless cockroach infestations were gone. In their place: brand new pipes, fresh drywall and — on the night of the party — a DJ and beer.

The new owners invited neighborhood artists and potential renters to see their handiwork. The young crowd filled the halls and poked around apartments-turned-pop-up art galleries for the night.

But one door remained locked during all of this. On the other side, Sherry Godat and her cat waited the party out.

Godat is one of several tenants who invited KPBS and Voice of San Diego into their homes in late 2014 to share evidence of dangerous and illegal housing conditions for a joint investigation into Bankim Shah. The San Diego landlord owned nearly 90 properties throughout the county at the time, including the Barrio Logan building where Godat lives.

Stacks of code compliance complaints, inspector reports and interviews with tenants revealed conditions state law has deemed illegal: gas leaks, sewage backups, missing windows and cockroach infestations. The paper trail also revealed lax code enforcement by the city that let the conditions persist.

Since the report, the city has added code enforcement officers and restructured the division that handles tenant complaints. Shah made some repairs to his buildings and sold 17.

One of those buildings was Godat's. She has a legal settlement with Shah that allows her to stay in the building through December.

But all of her old neighbors are gone. And what happened to them tells a story about San Diego's current housing crisis.

RELATED: Decade-Old Law Could Protect San Diego Tenants — Or Not

Displaced tenants land on couches

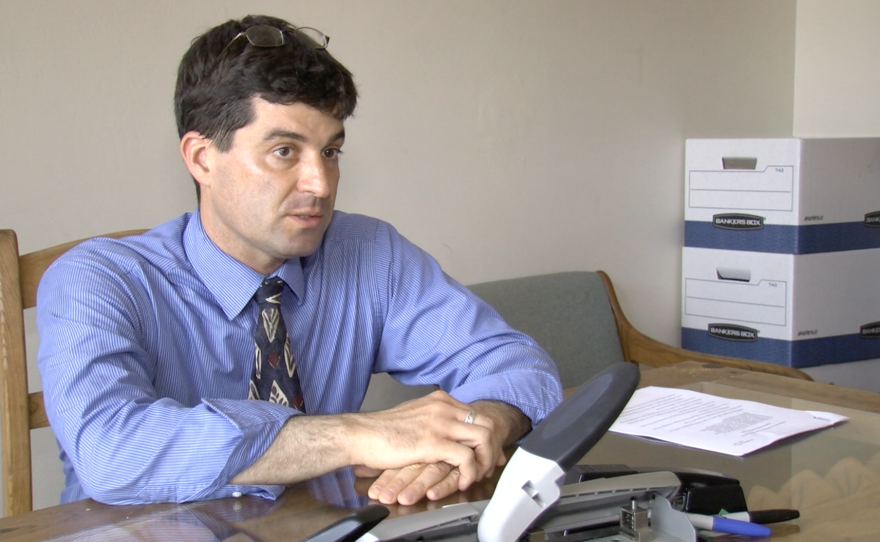

Tenants' rights attorney Dan Lickel, who represented some of Shah's tenants before and after the sale, said many ended up in other dilapidated buildings or on couches.

"In the last year I've seen a number of buildings that were sold," Lickel said. "The new owner comes in and decides they want to renovate and as a practical matter tenants are asked to leave — tenants who had been in these places for, in some cases, 20 years."

Lickel said he's seeing more and more tenants displaced as properties in cheaper neighborhoods like Barrio Logan and City Heights change hands.

"They have to go find other housing in a market that doesn't really have a lot of affordable housing," Lickel said. "Either that or tenants have to move further out. They have to move out to East County."

And even that's getting tough. East County, where housing has traditionally been more affordable, has the lowest vacancy rate countywide at 1 percent. A low vacancy rate means there are fewer available homes and landlords can command more in rent.

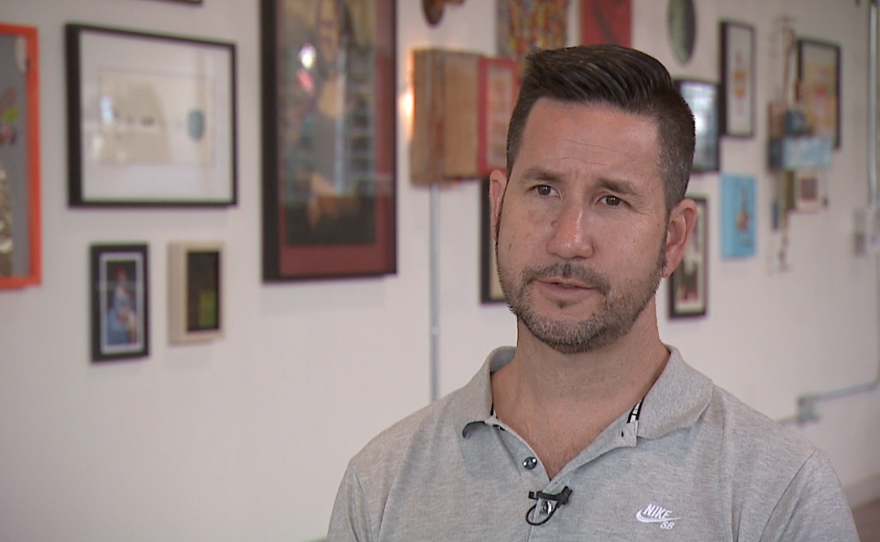

Greg Strangman, the founder and lead principal of LWP Group, the firm that bought 2605 Logan Ave., said he sympathizes.

"Each building has its own situation. Sometimes we renovate buildings unit by unit as they become vacant, because the building is just in better shape than others," Strangman said. "This building ended up being an example of just code compliance violations and just uninhabitable things."

Strangman said when he took possession of the property, water was leaking into downstairs units from showers and tubs above. He said the apartments had mold and vermin.

"Hot water was a big one, because they didn't have a tank on each building," Strangman said. The property includes two apartment buildings. "They only had one tank on one side of the property and they were piping it over to the other property. So getting a situation where people didn't have to wait 15 or 20 minutes to gain hot water was something we wanted to take care of."

Strangman said conditions were so bad it would have been irresponsible to keep tenants around during the renovation. All were given notice to vacate. Strangman said he told tenants they could reapply for units after the six-month renovation, but none have.

When the work was done, the units went back on the market for $900 to $1,200, which is in line with the average rent for Barrio Logan.

"I realize we're kind of in the artistic space, but we're really offering workforce housing," Strangman said. "In today's time, when the average rent in San Diego County is over $1,700, we're still very much workforce housing."

A game of musical housing

But some of the previous tenants were paying as little as $650 dollars a month. They represent a subsection of San Diego renters whose incomes would qualify them for Section 8 rental assistance or other subsidies, but they're waiting to get into the program — it has a decade-long waiting list — or their immigration status or a past eviction disqualify them.

Stephen Russell heads the San Diego Housing Federation and said it's these very low-income renters who are seeing the worst of San Diego's housing crisis.

"The rental market is like a game of musical chairs. The person who has the most money gets to sit down first," Russell said. "And that's a very simplified notion, but it's easy to see where those with the least money are ultimately bid out of the market. There simply is not enough supply in the city right now."

Russell said that when home building slows, more well-off renters are willing to move into previously undesirable units.

"Usually, if there's a healthy pipeline of housing in a community, there would always be housing that is aging out or filtering down to affordability," Russell said. "Unfortunately in San Diego, because we've had such constraints on housing production, we don't have that pipeline of continuously aging housing.

"So in a market like what we're seeing right now where vacancy rates are extremely low, there's an opportunity for landlords to take these properties and fix them up. But of course to do so they have to finance these improvements and see the return. What that means is naturally affordable housing being upgraded and is now no longer considered affordable."

Russell said the market is so constricted right now that landlords who flip their older housing see a return in three years, as opposed to five in a more traditional market.

He said the only way out of a market in which displaced, low-income renters land on couches is to increase homebuilding, including subsidized affordable properties.

Strangman said he does his part by not charging exorbitant rents, and agrees that building more housing will solve the problem, especially if the units are smaller and cheaper to build.

"The interesting thing is all the buildings that I work on are older existing buildings that were built somewhere between 1906 and the '60s. But most of those units when they were originally built were built as smaller homes, and people lived there," Strangman said. "We had a gentleman living in our Carnegie Building (downtown) for 45 years in a studio. I think we've kind of gone to the McMansion side of things and I think the pendulum needs to swing back the other way where people realize maybe they don't need all that."

It's a conversation happening more and more as the housing market's squeeze tightens. The conversation is usually framed around numbers — add more units, bring down demand and rental prices will follow.

But the ugly side is this: for years, poor tenants have turned to dangerous housing like Shah's to afford a roof over their heads. And now even that is disappearing.

Sherry Godat — the woman in the corner unit who didn't join the party — did not want to be interviewed for this story but said in a text message she expects to be homeless when her lease ends in December.