Golf may be an expensive sport that isn't known for being diverse, but a program in City Heights is bringing immigrants, refugees and other low-income children into the game. The goal: help them excel in school.

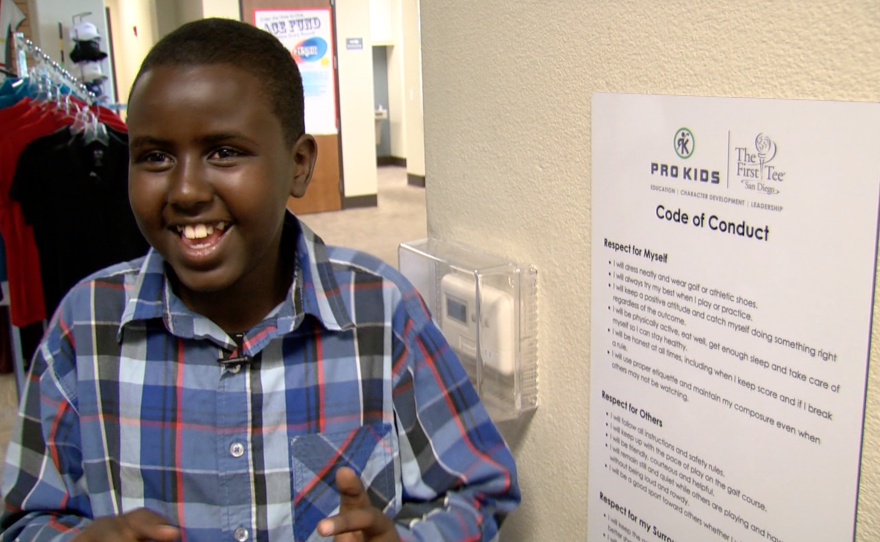

Zubeyr Mohamed, 12, is the son of Somali refugees. He has been playing six days a week for four years at an after-school program called Pro Kids. Like most members, he receives a fee waiver because of his family's lack of financial resources.

Along the way, Mohamed has polished his game. He said he has also learned some life skills such as patience and persistence.

"Honestly, you can’t give up on anything. And at the same time, you have to be patient ‘cause you can’t rush to things, you know?” Mohamed said.

Each of the 18 holes at the 14-acre, par-3 Pro Kids golf course corresponds to a different value, including patience, persistence, honesty and confidence. More than half of the 1,500 students who train there are immigrants or refugees. Students from partner elementary and middle schools can join Pro Kids for physical education credits.

“In the old times, mostly rich people and wealthy people wanted to play and said that other people, the common people, could not play,” Mohamed said. “And that was not right, as you may know.”

Pro Kids was founded in 1994 by Ernie Wright, a former Chargers player who worked as a caddie at an all-white country club in high school. He wanted to help children like Mohamed play golf. He also wanted to connect them with academic tutors, scholarships and education trips, such as pro-golf tournaments.

He fixed up a rundown golf course in City Heights.

In 1997, the international organization First Tee launched and operated under the same principles as Pro Kids. Pro Kids became a chapter.

“Now, it’s a sport for anyone,” Mohamed said.

The City Heights golf course is next to a Pro Kids education facility where students can do their homework and receive tutoring.

Mohamed’s mother, Maha Hussein, worked to advocate for women’s rights and raise HIV awareness in Somalia. She received death threats, and in 2001, she was forced to seek asylum in the U.S.

Hussein said Pro Kids has helped her keep Mohamed and her other U.S.-born children on the right track, offering structure while she’s working 56-hour weeks as an elder care provider.

“My son, he was chubby, he was frustrated after school sitting at home. Now he is a very handsome boy,” she said.

Hussein said the program’s academic support is paying off. Mohamed is getting straight A’s.

“I think it’s a brain game,” she said. “I don’t know how it works, but since the kids playing now, I feel like they’re achieving more. They’ve become very smart!”

Pro Kids CEO Keith Padgett has a theory about why the program works. He said children learn geometry and physics on the golf course.

“It’s all about angles,” he said. “Your swing is an arc. We have kids learning how different surfaces affect the rolling of the ball.”

The program also promotes ethical values that can help children both inside and outside of the classroom. Padgett said golf is the only sport where players must call penalties on themselves.

“If that ball moves, you take a penalty,” he said. “You call it on yourself. You don’t need somebody over here to say you just violated a rule. You’re supposed to report that.”

Pro Kids also uses a point system for members to purchase golf gear and fun activities.

“To play golf, they have to get good grades,” Padgett said. “They have to be good citizens. They have to mentor other kids.”

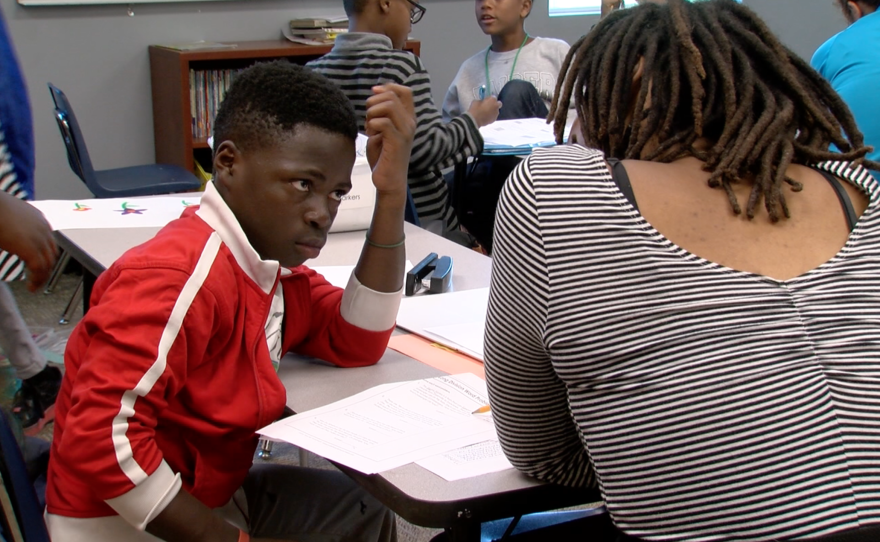

Nasteho Ali, a fifth grader whose parents are also from Somalia, recently did her homework at Pro Kids. She said golf has helped her with math.

“Because you get a number of strokes on a hole, and you need to add it up on your scorecard, and in school, I’m also doing addition. So it helps in school,” she said.

Her mother, Maryan Ali, never imagined she’d have kids in the U.S. playing golf.

“Oh my God, I didn’t know anything about golf!” Ali said.

When Ali first ran away from her home to escape the civil war, she hid in the jungle, eating mud and grass to survive.

She was granted asylum in the U.S. and sent to North Dakota, where it was snowing. She had never seen snow before. The sight sent her into shock.

“I was like, you know what, I want to go back to the refugee camp where I came from,” she recalled. “If I die, this is where I’m going to be buried, under the snow? I say no, please!”

But then she got a call from a friend.

“And she said San Diego is like Africa. Same. You can see the ground, the sky, the grass — everything," Ali said. "(My friend said), 'You need to come over here.'”

So she moved to San Diego. She had never seen a golf course before before she arrived. Now she has five children who are golf players.

Ali recently tried to the sport. She thought it was going to be easy, but her children told her she was doing it all wrong: her posture, her grip on the club, her putting technique, everything.

She said golf isn’t as easy as it looks. But Ali enjoyed the effort, and plans to try again.