Jose Luis Hernandez was 17 years old, riding the roof of the infamous Mexican train La Bestia toward the United States when he fainted or fell asleep.

He was in Delicias, Chihuahua, more than halfway to his destination, but he was hungry and exhausted. The Honduran refugee hit the ground. Then La Bestia did to him what it had done to hundreds of other Central Americans: it sank its wheels into his limbs.

“I looked at my leg, trapped, and I tried to free it with my arm, and the train also tore off my arm,” he said. “Half unconscious, I tried to free my arm with my left hand. It mutilated my left hand.”

Hernandez is 30 now. As he recalls his dismemberment, one sleeve of his white T-shirt is empty, and he's wearing a prosthetic leg. A black glove covers what remains of his left hand. He ascribes his survival to a miracle. A Red Cross worker witnessed his fall and called an ambulance.

This month, Hernandez and three other dismembered Hondurans are in San Diego raising awareness about the dangers of migration. Like millions of Americans who support presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump’s proposal to erect a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border, Hernandez would like his countrymen to stop migrating to the U.S.

But Hernandez has a different idea about how that can be achieved. For years, Hernandez said, the U.S. has failed to stop illegal immigration from Latin America because it has misunderstood the essence of what motivates those migrants.

“The American dream doesn’t exist,” Hernandez said. “What exists is an essential need, a forced migration. We don’t come here to go to the beaches of Miami or the casinos of Las Vegas. We come here to work like donkeys, sometimes for terrible wages.”

The migrants know the risks of taking the journey: robberies, rapes, dismemberment, death. They make the journey anyway. Hernandez argues that fences and customs officials fail to deter migration for the same reason the risk of death or dismemberment fail to do so: it’s a matter of life or death for the migrants.

After his dismemberment more than a decade ago, Hernandez returned to Honduras, where he formed the Association for Returned Migrants With Disabilities, which educates people about the risks of migrating.

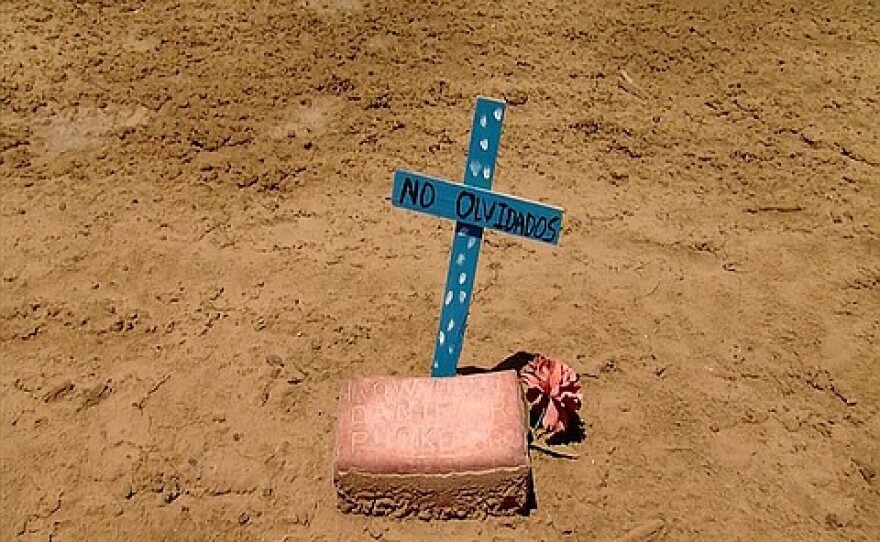

So far, the association has documented 713 cases of Hondurans mutilated by the train in the last six years. In addition, 362 Honduran bodies have been sent back for burial. About 3,500 Honduran migrants have vanished while traveling through Mexico.

The association is advocating for improving the economies of Central America, so that migrants won’t want to risk their lives to reach the U.S.

“Migration will only stop when our countries truly generate employment opportunities with fair wages,” Hernandez said.

A year ago, Hernandez and his friends were granted asylum in the U.S. They sought an audience with President Obama.

“The United States exerts a lot of influence in our countries,” Hernandez said. “If the United States tells our president to worry about the people, it will happen. Central American countries, whether we want it or not, are puppets of the United States. They dance to the rhythm of whatever music this country plays.”

He said the current U.S. strategy of investing billions of dollars to boost customs enforcement along both the U.S.-Mexico border and the Mexico-Guatemala border is only increasing injuries and fatalities.

David FitzGerald, co-director of UC San Diego’s Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, said Mexico’s Plan Frontera Sur, which boosts Mexico’s deportations of Central Americans with U.S. financial support, forces migrants onto more dangerous routes through Mexico.

He said the U.S. has been using Mexico as a “buffer state” to keep refugees from Central America from reaching the U.S. Now, Mexico's deportations of Central Americans are twice as high as those from the U.S.

“There’s a high human cost to this kind of buffer policy,” FitzGerald said.

During a news conference with Border Angels, a San Diego-based nonprofit that helps migrants, the four mutilated Hondurans urged San Diegans to demand a change of course from the U.S. government.

They said they traveled to San Diego from Maryland because five other members of their association were detained at the San Ysidro Port of Entry earlier this month. They are calling for their release.

Customs and Border Protection confirmed that the Hondurans' friends had been detained at the Port of Entry, but said they were no longer in the agency's custody. Immigration and Customs Enforcement did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Everard Meade, director of the University of San Diego’s Trans-Border Institute, spoke at the Border Angels event alongside FitzGerald and the Honduran migrants. He said the current immigration debate is "obsessively focused" on the U.S.-Mexico border. Meade said that doesn't make sense because immigration from Mexico is at a historic low.

“The one crisis we do have related to the border has to do with declining conditions in Central America, and the U.S. relationship with those countries,” he said.

The flow of Central American migrants is rising again, despite initiatives like Plan Frontera Sur, he added.

“We’re repeating strategies that have failed in the past and will fail again,” Meade said.

Speaking at the news conference, Hernandez agreed with the experts, saying he has come to the U.S. to help Americans put a face to the consequences of what he believes are failed immigration policies.

"We have to attack the problem at the roots," he said. "Only that will stop migration—when our officials start worrying about us. Only then will the mutilations stop, and the deaths, hundreds and hundreds of bodies. "