This is KPBS Midday Edition. I'm Maureen Cavanaugh A combination of fear and violence and escape from poverty are bringing a new wave of migrants to Tijuana. People from central and South America are there. Many are originally from Haiti. Customs officials at San Ysidro are over -- overwhelmed. Pat Murphy is at the home of one of the main migrant shelters, Casa del Migrante . People here tell us, there are thousands of people behind us. These seek to enter the US, but Tijuana must address the situation. Casa del Migrante and three other shelters offer food and beds. When U.S. Customs is ready to process a few more people, Mexican migration officials at the shelters know. When they are placed in a line, they call us and we transport them to the front door. He says Tijuana officials aren't doing much else. They're relying on the shelters, which dependent donations. They have to admit, that this is not a temporary problem. This is going to continue for a while. Luckily, he says Tijuana residents are reacting with sympathy. The best news was the generosity of the people. Showing up and saying here's food. They realized they might have more to share pack Dustyn Pascal has been saying here for several days. He says the houses good, he made friends here. He says he moved from Haiti to Brazil to feed his family. He says there were not any jobs in Brazil, now he dreams of finding work in the US. He traveled to 10 countries to get here. When I asked why so many people are coming now, he said it's because it's Obama's last year as president. He said many more people are coming. Murphy says he's mystified by the influx. The million-dollar question, why now, why is this happening? Items I don't have a handle on that. Order protection says it's processing the migrants on a case by -- case basis. At nearby Madre Asunta, a woman's shelter I spoke with Guerlyne Mevil, she moved to Brazil seeking a better life . When she can earn enough to feed yourself, she embarked on a journey through Latin America. On the way, so many people died. It was a long way. She says she repeatedly collapsed on a seven-day stretch between Colombia and Panama. When we wanted to drink water to quench our thirst, we had to lick the sweat from our bodies. She thought she was not going to make it, when she saw others dying around her, but she kept going. On the way, you have two options, to live or to die. I was so lucky. At the shelter, the Haitian women watch their children play. They be from the Mexican and Central American migrants who are also there. Communicating and gestures and broken Portuguese. Mevil says she is grateful for the shelter , she's confident she will make it to the US. I didn't die on the way, I'm alive. She says she believes the hard part is behind her. Joining me now is KPBS Fronteras reporter, Jean Guerrero. What prompted these migrants to leave Haiti in the first place? It's a country with a lot of instability. It's currently the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, for in every five people live in poverty. They don't have enough food, sometimes they don't even have a home. The earthquake left more than 1 billion people homeless. Even six years later, the country remains dependent on foreign countries and international aid to manage its poverty. When you add the health crisis, such as the cholera epidemic in the Zika virus and the fact that there are not enough doctors are inadequate -- an adequate health system. It's a completely failing system. There isn't enough medicine. The money sent home by a Haitians working another country is what keeps him a folk. I read your report, many of these refugee, went to Brazil and now because of the problems of Brazil, they aren't being able to find work. In Brazil they encountered, originally there were jobs, because of the commodities boom. The situation deteriorated. Oil prices went down and the jobs evaporated. Exactly. Those -- there is a corruption scandal involving the president of Brazil. What chances do they have of making it to the United States? It's hard to tell. After they are processed bike customs, they are transferred to customs enforcement which determines whether they will be sent back to Haiti. They can't be deported to Mexico, they're not Mexicans. It's more complicated than when you're talking about Mexican migrants are Central American migrants. Haiti is overseas, it's more expensive to send them home. It involves buying fights and they have to get permission from the Haitian government. There is political chaos there, their interim president's term just expired. It's impossible to make the necessary arrangements. A last resort, US immigration can find another country that's willing to take them., It will likely be Brazil, many patients do cross the border into San Diego, without legal status, while waiting for the removal proceedings and others. There's a church called the Christ ministry center that's offering shelter to more than 200. I want to ask you, because we talked about it. We've heard the US and Mexico have set up order stops within Mexico, to stem the flow of migrants coming from Mexico into the US. Why are they working to stop them before they get to Tijuana? Mexican immigration officials tell me the Haitian migrants pretend they are from set -- other countries to avoid being deported. They will say they're from a number of countries in Africa, which Mexico has note diplomatic relations there, Mexican officials can't touch them they can't verify that. The migrants are simply following the footsteps of central Americans who continue to flow into the US, despite the greater customs enforcement and Mexico, they are taking more remote and dangerous routes to avoid detection. There's been a lot of criticism, because it seems to be increasing fatalities and other problems among potential refugees, without deterring the migrants. Is there any merit to son Pascal's belief that Obama will help this group? I don't know the answer. They seem to have an exaggerated perception of his policies, of his friendliness towards migrants. They believe they will be welcomed with open arms, like the Cuban migrants. That's never been the case. Haitian migrants have historically been considered economic migrants, rather than refugees. Most Haitians I spoke with, said they are here for economic reasons, although it's also a question of survival for them. The line between refugee and economic migrant players from their perspective. They don't feel they are going to live. They feel frightened for the lives, when they think about going back to Haiti. I imagine there is some concern, if Trump becomes president, it will be harder for them to enter the US, considering his immigration proposals. None of them have specifically said they are here because Trump could be president. They think it's a confluence of many factors. You mentioned in your story, to want to shelters are being overwhelmed by these immigrants. Where else is there for them to go? There's really nowhere else for them to go. There's a grassy area by the deported entry, just south of the Bo Hart -- border. Drivers are waiting in line to cross the United States through the port of entry will give them food or money when they see them there, most of the time they are read to direct -- redirected to the shelters by Mexican migration. The shelters work to save the migrants are spots in line at the border. The director of Casa del Migrante every afternoon, Mexican migration officials pick up 30 migrants to take to the shelter and pick up new ones.

Somewhere in the jungle between Central and South America, a 34-year-old Haitian woman collapsed of thirst and exhaustion, frightened she would die.

“Our throats were dry,” said Guerlyne Mevil of her group of Haitian migrants. “When we wanted to drink water to quench our thirst, we had to lick the sweat from our bodies.”

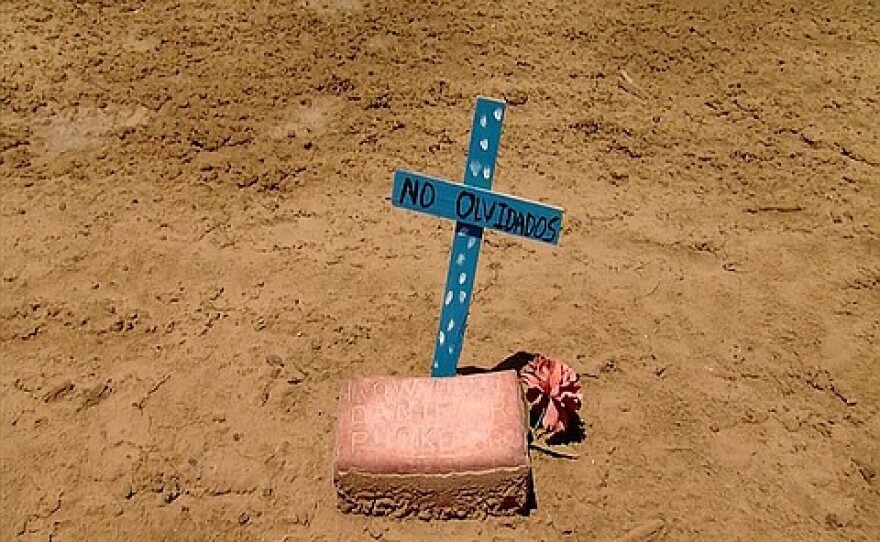

Mevil summoned the strength to stand up, determined to reach the U.S. and send money to hungry relatives in Haiti. She had already tried finding work in Brazil, in vain. But others who fell failed to get back to their feet.

“So many people died,” Mevil recalled. “On the way, you have two options: life, or death. I was so lucky. There were huge, strong men who didn’t make it.”

Mevil is a tall, full-figured woman with a singsong voice and curly brown hair, who describes the last two months of her life as a harrowing journey through Latin America by boat, plane, car and foot. She said a seven-day walking stretch proved deadly for some of her companions. Mevil is no stranger to death — she lost family in the 2010 Haiti earthquake.

In Tijuana, Mevil is staying at a women’s migrant shelter, Madre Asunta, awaiting a chance to speak with U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials.

“I eat well, sleep well, and they give me clothes,” Mevil said of the shelter.

She is one of hundreds of Haitians flowing into Tijuana since late May with plans to enter the U.S., mostly due to a dire economic outlook in Brazil, where many moved after the 2010 earthquake. Worldwide demand for commodities was then buoying the economy of Brazil, with its diversity of natural resources. But employment opportunities have since evaporated due to plummeting oil prices and a political crisis tied to Brazil’s suspended president, who is facing possible impeachment.

“They weren’t giving jobs to foreigners,” Mevil said.

Now, those migrants are coming north to the U.S.

Overwhelmed San Ysidro customs officials are relying on Tijuana’s migrant shelters for help while they catch up processing the rising tide of migrants, many of whom sleep on the sidewalk just south of the port of entry. Some seek political asylum. Some are from Africa. Most are Haitian migrants fleeing grim economic prospects.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection said in a statement that the agency will process these migrants on a “case by case” basis. While migrants await their turn, Tijuana's shelters offer food and a place to sleep. At Madre Asunta, the Haitian women made friends with women from Central America and southern Mexico, who were also staying at the shelter. Their children played together as they communicated in a mix of gestures, smiles, French, Spanish and Portuguese.

“We’re a family,” Mevil said.

She told a Mexican woman about her difficult journey through Latin America, concluding, “I have more lives than a cat.”

The Mexican woman responded, “That means you have six more,” and they giggled together.

Footsteps away from Madre Asunta, a men’s migrant shelter called Casa del Migrante is accepting Haitian men as well as some women and children, because there aren’t enough beds at the women’s shelter.

Director Pat Murphy called the influx of migrants a “crisis” and “an emergency.”

“People here have told us, ‘there are thousands of people coming behind us,’” Murphy said.

During an especially busy day last week, Casa del Migrante slept 56 Haitians in addition to about 150 migrants from southern Mexico and Central America.

In less than two weeks, Murphy said his shelter received migrants from 11 different countries, mostly from Haiti. Murphy said he considers them refugees.

Although these migrants seek to enter the U.S., Tijuana must address the surge during the immigration backlog.

Casa del Migrante and three other Tijuana shelters are offering the migrants food and beds. Mexican immigration officials let the shelters know when U.S. Customs and Border Protection is ready to process a few more people.

“When their place in the line is ready, they call us, and we transport them right to the front door of immigration,” Murphy explained.

But he said Tijuana officials are relying too heavily on the shelters, which depend on donations.

Haitian migrants came just as the shelter was seeing a spike in Central Americans and southern Mexicans fleeing violence, Murphy said. Some had to sleep on the floor.

He said he thinks Tijuana should open a shelter of its own, like those opened during heavy rains tied to El Niño.

“They have to just admit that this isn’t a temporary problem, that this is going to continue for a while,” he said.

In the meantime, Tijuana residents are bringing food, clothes and other donations for the Haitians, Africans and other migrants.

“The best news of all this was the generosity of the people, just showing up at the door, saying, ‘here’s food for 50 people,’” Murphy said. “Even though they’re not rich themselves, they realize, ‘I may have a little bit more to share.’”

Twenty-five-year-old Haitian Jeff Son Pascal arrived at Casa del Migrante in early June, also by way of a two-month journey departing from Brazil.

Like hundreds of other migrants, he slept on the sidewalk just south of the San Ysidro Port of Entry for the first few days. Then he was redirected to the shelter while awaiting his turn to see a U.S. immigration official.

He said he is grateful for Casa del Migrante, where he and other Haitians take turns helping with domestic duties, such as washing clothes and serving food.

“The Casa is very good, very good,” he said in broken Spanish.

Son Pascal embarked on his journey alone, without friends or family, but he said he has made many friends in Tijuana, both Haitian and Mexican.

He said he dreams of a better life in the U.S.

When asked how many people are coming behind him, Son Pascal sighed and said: “Many, many, many, many, many.”