I’m riding my bike along Broadway in the middle of downtown San Diego. There’s no bike lane, so I’m sticking close to the parked cars. Then a bus pulls up to a stop next to me, making me a little nervous.

Luckily, I have a guide.

Andy Hanshaw, the director of the nonprofit San Diego County Bicycle Coalition, is taking me on a ride to show me where new bike lanes would go under the Downtown Mobility Plan.

The plan was drafted by Civic San Diego and went through a series of community meetings. Now it's expected to go to the San Diego City Council for a vote on June 21.

If approved, it would add more than 9 miles of protected bike lanes in downtown San Diego, as well as more than 5 miles of widened sidewalks with benches and trees. It would also shorten street crossings and add more signs.

But the plan would also eliminate 477 parking spaces over the next 20 years, and eliminate some car lanes. So some businesses and residents are opposed to it.

As we ride, Hanshaw points out things cyclists downtown, or on any busy street, need to notice.

"Things as a bicyclist to think about is a car door that could open just like that one did," he said, as we rode past some parked cars.

Hanshaw's hope is that the Downtown Mobility Plan will make it safer and easier to bike downtown.

"It’s a forward-thinking network that’s proposed to go in at one time where bike lanes don’t even exist currently," he said.

A key part of the plan is that the lanes would be added as a network, Hanshaw said.

"So that you can actually plot and plan your trip to be in a bike lane the entire route," he said.

Many of the bike lanes would be protected, meaning there will be a physical separation between the bikes and car traffic.

The plan would add protected bike lanes on Pacific Highway and State Street; Fourth, Fifth and Sixth avenues; Park, J and C streets; and Broadway and Beech Street. It would also extend the bike lane on Harbor Drive and the bike path along the bay.

As we rode down Sixth Avenue, Hanshaw said he sees it as having too much room for cars.

"You can see three lanes on this street, with two sides of parking. That’s too much," he said. "There’s plenty of roadway for a bike lane."

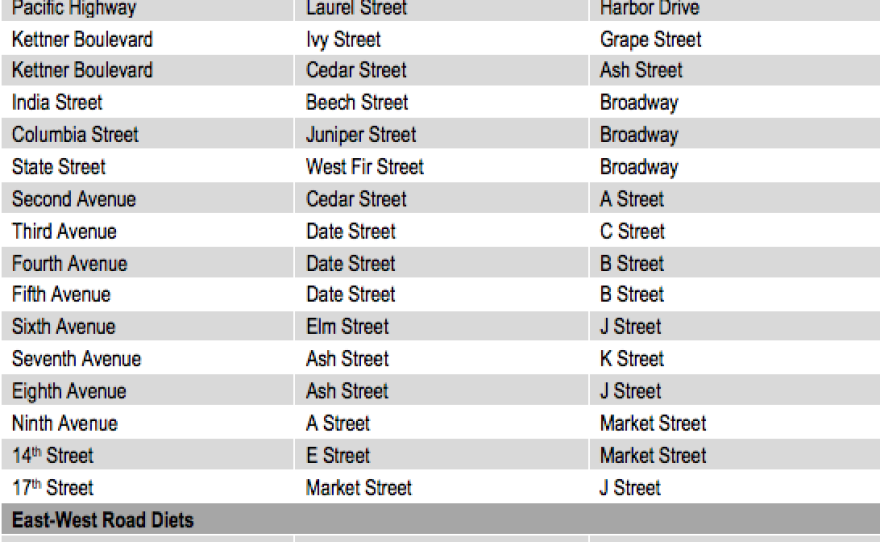

The plan would set up so-called "road diets" — meaning reducing a car lane or parking — on several downtown streets, including portions of Kettner Boulevard, India Street and Second through Ninth avenues.

One change that's attracted a lot of opposition is adding bike lanes to State and Beech streets in Little Italy.

Christopher Gomez, district manager of the Little Italy Association, said the traffic on those streets is already slow enough for cyclists to travel without a bike lane, and he worries about reducing parking that's used by residents.

"We would lose an additional 50 parking spaces on those two streets alone, which are in a residential and school and church corridor," Gomez said. "Those are in need of parking more than anywhere else in the district."

Some apartment buildings already only have one parking space per unit, he said.

"So, for example, you have a unit that has two bedrooms, you have someone who owns the unit or a husband and wife, or a roommate," he said. "Well, where is that other person parking?"

Gomez said he isn't opposed to adding bike lanes but wants them to go on Ash and A streets instead. He said downtown isn't ready to shift people away from using their cars and needing parking spaces.

"Our concern with a statement that says, ‘If we build it, they will come. If we have bike lanes, then less people would use their vehicles.’ The unfortunate part about that particular statement is there are not enough jobs in downtown San Diego," he said. "The people that typically work in downtown don’t live in downtown. They live in Chula Vista. They live in Kearny Mesa, etc. And those people that live in downtown don’t work in downtown. They work in La Jolla. They work in other parts of San Diego."

Hanshaw said the plan actually increases the number of parking spaces in the short term, and that by the time spaces are eliminated and the new bike lanes are built he hopes fewer people will be driving.

He said it will take changing car-centric thinking to embrace the plan.

"Especially in a dense, growing, thriving, urban downtown environment, the mind-set has to be about creating safer mobility choices for people to go to work, to go to restaurants, to go to sports venues downtown," Hanshaw said. "If we’re just adding parking somewhere else, we’re really not accomplishing our original goals of the plan."

He also points out that achieving the goals in the city's Climate Action Plan will rely on adding more bike lanes. The plan calls for increasing the number of people who commute by bike from 1 percent to 18 percent by 2035 for people who live within a half mile of existing or planned transit stops, which includes downtown.

If the plan is approved, the city will need to fund it. It's estimated to cost $63 million.

"If the city treats this as a priority, and I believe they should to achieve their own Climate Action Plan goals, then they will find the necessary funding to do it," Hanshaw said.

After we finish tracing the route of proposed lanes, Hanshaw and I stop our bikes. I’m happy to have safely ended our ride.