This is KPBS Midday Edition. Maureen Cavanaugh. It's been almost a year since hundreds of immigrants were forced out of the canals, KPBS frontier is G Guerrero went inside the titles to talk to the migrants. Gene welcome to the program. Thank you, Ray. Tell us more about this program, this is been a place for Tijuana's homeless have congregated for years. Pack More than 1000 people were living there in makeshift tents or just out in the open. Most of these people were deported from the United eggs and were waiting for a chance to cross again. Any of them had Emily on the other side. Subhead a hard time adapting to life in Mexico because they did not have official Mexican documents. So the government has cleared out the canal, last year, where did they go? Where did the people go whom were routed out of that were canal? Hundreds of these people were rounded up and placed in track rehabilitation centers around the city. Officials said that the homeless migrants were hurting tourism and committing crimes. Any of them were using drugs such as methamphetamine and heroine. But there were a number who were Soper replaced and rehabs. Over the past few months, hundreds of people's Heaven's Gate these centers or been released because of lack of funding. Now they are back in the canal, that they are in the dark tunnels that stem from the canal where they cannot be seen. And you went in these branching tunnels to talk to some of the people that are living inside them. What is it like inside the titles? Right now is very wet because of the rains we had earlier this year. Migrants are sleeping on these damn mattresses, wet blankets and some of them around the canal. You spoke with people. What did they have to tell you? Most of them say that they hide in these files because they don't feel safe anywhere else. The scenes of the police arrest them just for -- standing in the street trying to find work. In fact, police recently concerned conducting raids of the tunnels themselves, resting migrants while they are sleeping. One-man described what it was like to be. The police say that come with them. Why, because you don't have a day. Effect cans you pick me up. If I go to the dumpster because you pick me up. Why am I so filthy because you don't give us a chance to make. What you want us to do? Is Why can't the people working Tijuana? Officials say they don't arrest anyone who's not committing a crime. But dozens who said -- who were interviewed said they can't go out in public. How does the Tijuana Police Chief respond to the claims that they are being beaten by police. He said if this is happening, he was the migrants to report this. But they are free to go anywhere near PlayStation or a government office because of how frightened the feel of police. You spoke to someone whose legs were broken in the tunnel. I didn't. It seemed that he was on his last breath. He was in a lot of pain. He had been run over by a car today's prior while running away from police during one of the rate of the canal. That is because these branching tunnels are underneath a major highway, is that right? Yes it is linked by major highways. The government has plans, right from your report, to clear out these canals again and to clear up the tunnels. How are they going about it? The police chief says he is planning a full-scale takeover vehicles that they will be getting a coming weeks. He calls the canal a no man's land, and he wants to put on the migrants either back in rehab, in general, or back to the birth cities. He expects the vehicles to write by Midshipman February. Thank you very much, I've been speaking with G Guerrero, KPBS Midday Edition. -- Jan Guerrero -- Jean Guerrero.

Underneath Tijuana, in miles of dark tunnels branching from a river canal, live hundreds of homeless migrants. Amid rats and sewage, they hide from municipal police who seek to place them in drug rehabilitation centers, in jail or on buses out of town.

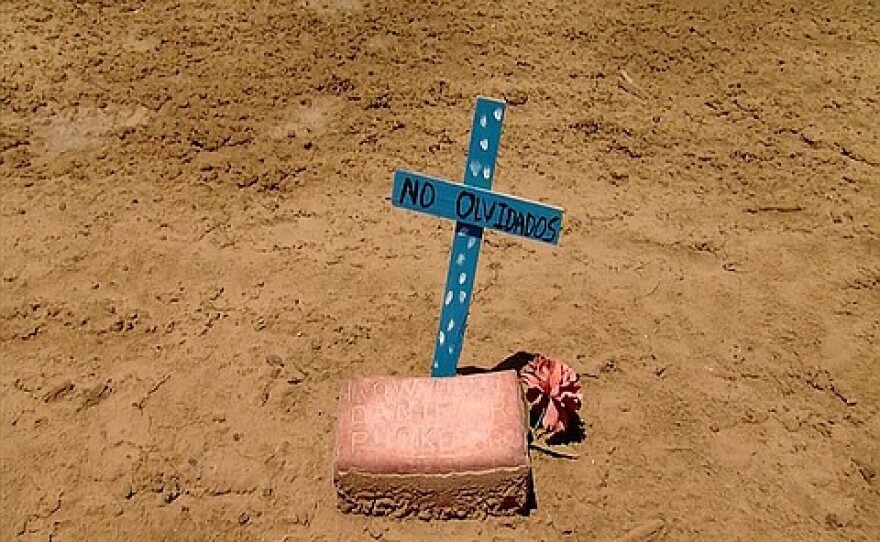

Bloodstains and memorial crosses on Tijuana’s busiest highways reflect a dying struggle. The Tijuana river canal is flanked by two highways, La Vía Rápida Poniente and La Vía Rápida Oriente, where cars speed upwards of 60 mph. When migrants try to outrun the police, they sometimes leap into traffic. Some are struck and killed. As police launch weekly raids of the canal, the migrants are dwindling in number.

The migrants often have tattoos of “San Diego” and the names of other California cities — the places where they have family. Many were deported. Unable to adapt to life in Mexico, they moved into Tijuana’s literal underworld, in the canal that converges with the border dividing the U.S. and Mexico.

Many cling to the dream of crossing back into the United States. Most lack official Mexican documents. Some use heroin and methamphetamine. Others are sober. Officials say the tunnel dwellers commit crimes, suffer addiction and hurt tourism.

In an interview with KPBS, Tijuana Police Chief Alejandro Lares Valladares said he is planning a full-scale clearing operation of the canal. He awaits the arrival of 14 new all-terrain vehicles he ordered last year. He intends to use them to flush out every migrant in the coming weeks.

"We’re going to take over the whole ravine," Lares said.

The initiative extends a partial evacuation from last spring, when hundreds of migrants were removed from a canal encampment near popular tourist attractions, including the bars of Avenida Revolución, and placed in rehab.

A KPBS investigation found widespread complaints of human-rights abuses. Many were taken against their will. Some were not addicts. Over the past few months, hundreds have escaped or been released. They have moved deeper into the canal's labyrinthine tunnels. No light reaches those parts. The highways rumble and roar above those who sleep.

"It’s a no man’s land," Lares said.

A homeless ‘El Chapo’ hides

Jose Alberto Zavala is known as Chapo, like the Mexican drug lord Joaquín Guzmán. Chapo is slang for “short” in Spanish. Zavala is about 5 feet tall.

When KPBS first interviewed the Tijuana homeless migrant, Chapo was cradling a wet tabby kitten he had rescued that rainy day.

“She’s a girl,” he said, stroking her head near the entrance of the tunnel where he sleeps.

The kitten’s paws and crooked whiskers trembled with cold. Chapo pulled her closer. With a wry smile, he said, "I found her in the canal. Do you think I was going to arrest her? No!"

Chapo owns a single hoodie. It’s brown, with the word "Rockstar" emblazoned along the front in capital letters. He said the police arrest him whenever they see him on the street, even if he is just trying to earn a few pesos for lunch by wiping car windshields or collecting discarded cans for scrap metal to sell.

"That’s a kidnapping," he said. "What they do is a violation of human rights. So long as the migrant doesn’t offend anyone, doesn’t disrespect anyone, they should let him be. But no, the officers come with huge guns, their submachine guns, as if I was El Chapo Guzmán himself."

Lares denied arresting migrants who are working. He said police detain only people who are committing crimes, such as stealing, selling drugs or sleeping in the canal, which is federal property.

Overall, crime in Tijuana is dropping, in part because of the city’s strategy of removing homeless migrants from the canal, Lares said. The federal government has jurisdiction, but municipal police obtained permission to patrol the area last year.

"For each person that used to live in that area, (they) were committing around one to three crimes a day in order to subsidize his living," the police chief said.

Most homeless migrants have since received treatment for drug addictions or been shipped back to their birth cities in Mexico's interior, he said.

Between January and November of last year, 39,747 crimes were reported in Tijuana, the lowest number in more than a decade, according to a police report. Car theft and house burglaries dropped 16 percent during that period. Meanwhile, homicides rose 34 percent.

Panic proves deadly while fleeing police

Chapo sleeps on a damp mattress deep inside a dark tunnel he calls "Apartment No. 1," where police can't see him when they enter the canal. But he must emerge to eat and work.

Dozens of interviewed migrants said they had witnessed friends or acquaintances killed in collisions, usually while trying to escape from police. After years of experience sprinting across the highways, the tunnel dwellers have become fast — so fast the police have a hard time catching them, especially when they hurl themselves into the Vía Rápida highway.

Most have learned to time their dashes across the highway, dodging even drivers who accelerate when they spot the homeless migrants.

The migrants also watch and protect one another. During two recent KPBS visits, men stumbling and falling down the canal’s lip toward the highway — seemingly under the influence of drugs or alcohol — were pulled back by friends.

It’s when the police come that migrants panic. Afraid of being taken to rehab or a nearby jail known as “La Veinte,” they take risks they otherwise would not. On Jan. 12, a 27-year-old migrant whom everyone knew simply as Daniel was stopped by police as he walked along the edge of the canal, according to witnesses. He ran into the Vía Rápida Poniente and was struck by a car.

“The car killed him like this, bam, just cracked him. But why?” Chapo said, visibly agitated. “Because of their fault, they’ve killed friends of mine. They’ve killed so many friends of mine.”

Lares said his officers can’t be blamed for the people who die crossing the highway, saying those who are killed are under the influence of mind-altering substances.

"It’s not because we provoke them," he said.

Since December, at least five migrants have reportedly died trying to escape police on the highways, according to witnesses. Chapo listed the three most recent: Chapitas, “a guy from Oaxaca,” and Daniel. He crossed the highway to kneel before a wooden cross he erected for Jorge Angel, a friend who saved him from drowning when the canal flooded years ago, because Chapo can’t swim. He said Jorge Angel was killed running from police last month.

"They kick you and say you have to come with them," Chapo said. "Why? Because you don’t have an ID. Because you shouldn’t be sleeping here. Well, where do you want me to sleep if you don’t let me work? Where do you want me to sleep? If I go collect cans, you pick me up. If I go to the trash heaps, you pick me up. I’m filthy because you don’t even give me a chance to bathe. What do you want me to do, official, sir?"

He said the police leave the migrants with few options but to turn to petty crimes such as burglary and theft.

A no man's land

Tijuana Mayor Jorge Astiazarán, a physician, appointed Lares as police chief in 2013. They met while working together at Tijuana’s Red Cross. The two men look similar: graying hair, brown eyes and fair skin. Both speak perfect English.

Last year, the duo decided to make rehabilitating homeless migrants who suffer from addiction a priority. Spearheaded by the mayor, the initiative was part of a mission to improve Tijuana in the eyes of tourists, and make residents and visitors feel safer walking around the streets. Before starting as police chief, Lares was the border liaison officer for Tijuana.

Earlier this week, Lares traveled to Mexico City seeking federal funds to pay for the rehabilitation of the rest of the migrants in the canal.

Questioned about alleged police beatings tied to the canal sweeps, Lares said migrants should file complaints so he can investigate.

"I’m not going to tolerate any abuse from an officer to a citizen," he said.

A dying man disappears

On a recent evening, in the canal near a street called “20 de Noviembre,” between 40 and 50 migrants gathered around campfires in the dark. Some agreed to be interviewed on condition of anonymity, due to fear of police retaliation. A few were nursing wounds they said they had acquired during recent police raids.

As some migrants carried one man out of the canal, he moaned in pain. They laid him on the ground. His injuries were so severe he couldn’t walk. His face was pale.

"A blanket, a blanket, please," he said, begging for a blanket to support his injured legs and whimpering.

A woman arranged his legs and he agreed to speak, his voice trembling. He said he had been hit by a car while trying to run away during a police raid two days prior.

“They come and they grab us, they ...” he paused with a grimace. “They beat us.”

He said his friends took him to Tijuana’s public emergency room at the Hospital General, fearing he was paralyzed, and that the staff turned him away.

"They treated me like an animal," he said. "Because I’m an addict."

His friends said they had similar experiences when seeking medical attention at the hospital.

"They ask for our address, our social security number," one woman said. "When we tell them we live in the canal, they reject us."

Early last year, during a visit to a Tijuana migrant shelter, the director of Mexico’s National Council Against Discrimination, Ricardo Bucio, said migrants face high levels of discrimination in the border city.

Bucio described a widespread xenophobia toward all outsiders except those with purchasing power, such as tourists. Most of the migrants who live in the canal are dark-skinned Mexicans, reflecting their roots in poverty-stricken southern states with large indigenous populations, such as Chiapas and Guerrero.

"I think it’s obvious, for anyone who has had contact with this reality, that discrimination is tied up with the phenomenon of migration in Mexico," he said.

Staff members at Hospital General denied discriminating against the homeless migrants of the canal, saying people requiring emergency medical attention are always given treatment.

But general animosity toward the tunnel dwellers exists. One man with a business by the canal said migrants emerge from the canal every morning to roam the streets, resembling what he called "a zombie apocalypse."

When KPBS returned to follow up with the badly injured migrant on Jan. 18, he was gone. His friends said the police conducted another raid on Jan. 16 — the day after our last visit — and took him because he couldn’t run like the others. On the next day, another migrant was killed in a collision while trying to outrun the cops, they said. They pointed toward the Vía Rápida Poniente, where three lanes were dark red with dried blood.

In an email, Tijuana’s police chief denied knowledge of these incidents, but said he would investigate. Three days later, the badly injured migrant, Carlos Francisco, was back in the canal, much recovered in a wheelchair. Police had dropped him off at Tijuana’s Red Cross.

'The Drunkard' feeds his friends

Cesar Jiménez Sánchez is known among homeless migrants alternately as “The Drunkard” and “Our Leader.” His eyes look black from afar, but when the sun catches them, they are yellow. He drinks almost as prodigiously as he works.

Jiménez has a more muscular build than his friends, as well as a broader skill-set thanks to more than three decades as a construction worker in the United States. He secures more jobs than others.

Chapo said Jiménez helps him and others survive, buying everybody tacos with any extra money he earns.

“He helps us,” Chapo said. “He brings us food.”

Acknowledged this way, Jiménez becomes sentimental and starts to cry.

For the past six years, Jiménez has spent almost every day from 6 a.m. to 3 p.m. on a Tijuana street, footsteps from the canal. He holds up a sign advertising skills as a construction worker, a plumber and an electrician.

At night, he often runs across the highway to sleep in tunnels. It’s the only place where he has ever felt safe in Tijuana.

He no longer dreams of returning to the United States. He has eight children in Los Angeles but was deported after a drunken driving incident. Increased border security and high smuggling prices have killed his hopes of returning.

Instead, he sticks to his work schedule, hoping to start a new life in Mexico.

“It’s hard to accept I’ve lost everything,” he said. “I can’t accept it. I can’t accept it yet.”

His voice breaks as he wipes tears away with a calloused, dirt-covered hand.

"I have been here six years," he said. "And in these six years, I haven’t been able to adapt to the world here. I’ve tried. But I can’t."

He said part of the reason he can’t assimilate is because the police make it so difficult. Jiménez said he has repeatedly been placed in the "La Veinte," or jail, while trying to find work on Las Rocas.

Still, he refuses to feel sorry for himself. He said Chapo and other friends have a much harder time than he does.

Chapo doesn’t know how to build houses or manipulate electrical wiring. Instead, he must rely on rummaging through trash bins for discarded tools and materials he can sell, such as copper wiring. Sometimes he sweeps storefront sidewalks for business owners who can spare some change. Other times he works as a construction assistant to Jiménez and other migrants.

He said he respects the intellect of the police chief and the mayor, because he considers it superior to his own. But he questions their empathy.

"It’s not that they’re not smart. The thing is, they don’t have a heart. They don’t have a heart," Chapo said.

The logic of their mission to remove migrants from the canal is beyond his comprehension.

"This is the border," he said. "There will always be migrants. Always, always."