The tale of the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station’s death involves big characters, big secrets and big customer bills.

There’s a watchdog agency, a U.S. senator, a governor and a state attorney general.

The California Public Utilities Commission is the beat cop for the state’s utilities.

“The problem is they’ve behaved more as if the FBI had put John Gotti in charge of the organized crime task force,” said consumer advocate Charles Langley.

Four years ago this month, the San Onofre nuclear power plant leaked radiation. Customers have since taken a multi-billion-dollar hit on the plant’s premature closure. And despite revelations about what Southern California Edison, the plant’s operator and majority owner, knew before its flawed equipment was installed, the company has mostly escaped accountability.

The CPUC promised an inquiry in late 2012 into what went wrong at San Onofre.

Administrative Law Judge Melanie Darling presided over that investigation.

Emails show Darling somehow learned of a report called the Mitsubishi Root Cause Analysis just as the probe got under way. The report said designers of the faulty San Onofre equipment knew of flaws and wanted to make changes before it was installed. But Mitsubishi said it didn’t make the fixes, in part because Edison thought the changes would impede the utility’s ability to avoid a deeper government review.

After finding out about the Mitsubishi report, Darling did something curious: She discussed with Edison in an email whether it would be made public.

Darling declined comment for this story. It was announced this month that she has retired amid a criminal investigation involving the CPUC and the shutdown of San Onofre.

John Geesman, an attorney for the Alliance For Nuclear Responsibility, said Darling’s secret communication with Edison raises ethical questions.

“Is that something that a judge sitting in a contested dispute would rightfully consult with one of the litigants without having all the other litigants involved in the same communication?” Geesman said.

Darling also did another curious thing. In December 2012, she decided to delay the San Onofre investigation by two years.

Two months later, someone leaked the same Mitsubishi report on the faulty equipment to U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer. Unlike Darling, Boxer called on the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to open an investigation.

The California Democrat’s push for an inquiry prompted a series of emails at Edison and the CPUC. Utility officials and regulators made plans to head abroad.

In March 2013, then-CPUC President Michael Peevey met secretly with an Edison executive in Poland.

There they wrote a framework for a San Onofre settlement that ultimately handed customers a $3.3 billion bill for the plant’s shutdown. Consumers also are spending several billion dollars more on replacement electricity and the construction of new power plants, meant in part to offset San Onofre’s loss. Besides Edison, the plant’s other owners are San Diego Gas & Electric, with 20 percent interest, and the city of Riverside, with 2 percent interest.

“The Public Utilities Commission took care of Southern California Edison shareholders,” consumer advocate Langley said. “They didn’t take care of the ratepayers.”

But in Washington, Boxer still searched for accountability.

In May 2013, the senator said she had “evidence of misrepresentation and safety lapses” by Edison and asked the U.S. Justice Department to launch a criminal investigation.

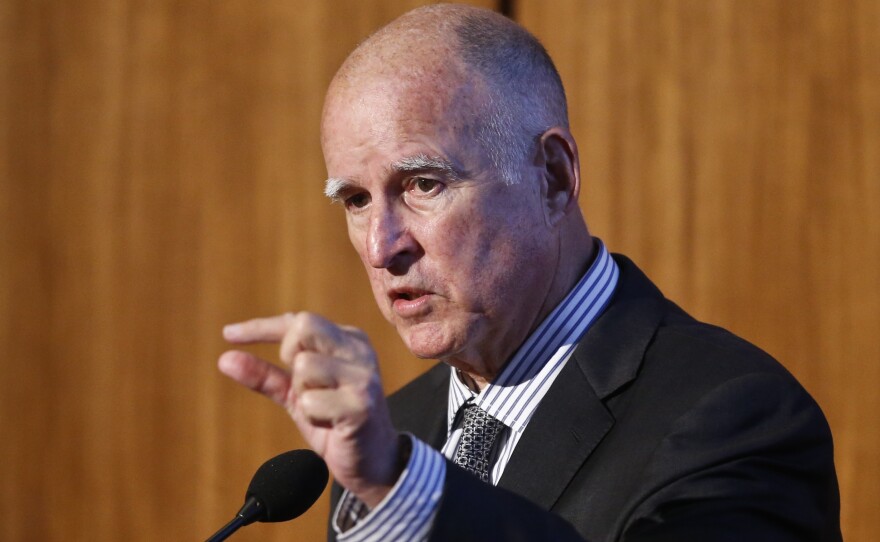

Several days later, Edison’s CEO Ted Craver told his board of directors in an email that Gov. Jerry Brown phoned him and asked if he was going to “blast” the senator.

A Brown spokesman has denied the governor asked that.

San Diego consumer attorney Mike Aguirre said Brown should have publicly backed backed Boxer in her call for a criminal probe of Edison.

“What it says is, the governor was more interested in keeping the support of Edison than he was in supporting the public’s right to not be burdened by Edison’s mistakes.”

Last year, Brown also vetoed a set of reforms intended to make state regulators and utilities more accountable. He said the reforms were important but too technical and conflicting.

Still, Edison has faced some accountability from the CPUC.

Darling, the administrative law judge, fined Edison almost $17 million for not revealing the secret meeting in Poland until two years later. But she also ended the commission’s investigation of San Onofre after the settlement was reached.

Aguirre said there are two systems of justice.

“There’s one system for most people, and there’s another system for people who are rich and famous like Edison and its executives,” he said.

Edison did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Ratepayer advocates hope California Attorney General Kamala Harris might inject greater scrutiny and accountability into what led to San Onofre’s demise and how a settlement was reached.

Harris has opened a criminal investigation. The probe appears focused on the secret Poland meeting as well as then-CPUC President Peevey’s plan for Edison to give $25 million to UCLA for greenhouse gas research as part of the San Onofre settlement.

There have been glitches in Harris’ investigation, though.

Harris has asked the CPUC for records dealing with San Onofre’s failure, but the commission hasn’t fully complied. The state attorney general, who is running this year to replace Boxer in the U.S. Senate, hasn’t pressed the matter in court.

Wednesday: How federal regulators handled San Onofre’s failure.