Carlsbad’s Measure A is not just a battle over whether to build a shopping and entertainment center on a coastal lagoon. It could also set a precedent for developers looking to save time and money on big projects in San Diego County.

California’s rigorous Environmental Quality Act was passed in 1970 and is designed to reveal the environmental consequences of new developments. The act demands a review of what could be done to mitigate any negative effects, or if nothing can be done, reasons why the project should go ahead anyway. It’s a high bar for developers to jump: a CEQA review can take years and millions of dollars.

California’s Supreme Court ruled in 2014 that a city could adopt a project without a CEQA review, if it passed a voter-sponsored initiative.

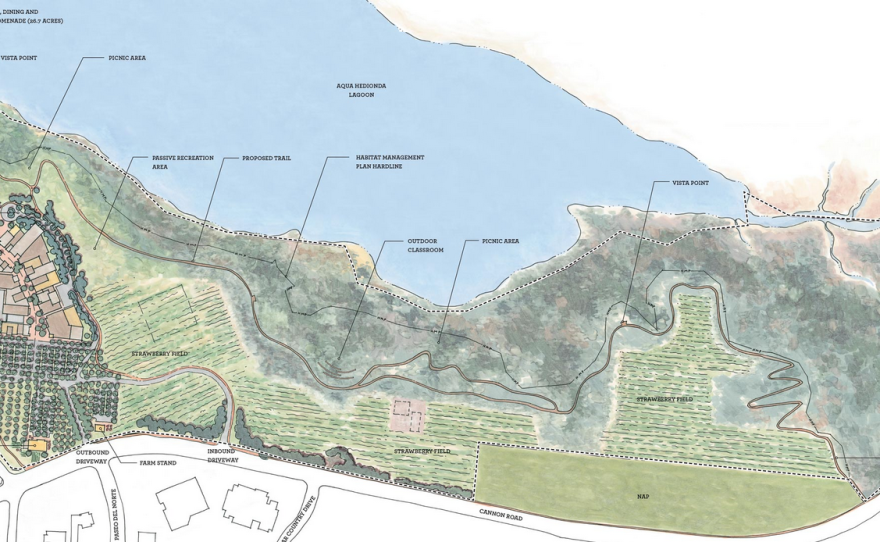

Los Angeles-based developer Rick Caruso decided in 2015 to try the initiative process and bypass CEQA and avoid the review. Caruso found the site on the Agua Hedionda Lagoon in Carlsbad more than three years before, and started working on a vision of an upscale, outdoor shopping, dining and entertainment center.

Caruso said the reason he decided to go the initiative route was not to save money but because a rival shopping mall developer, Westfield Corp., threatened to sue to stop the project under CEQA rules. Westfield has successfully blocked Caruso before: in 2011 Caruso withdrew plans to build a $500 million outdoor mall at the Santa Anita Park racetrack in Arcadia, after Westfield sued the city and put up a ballot fight.

"We used the initiative process because it is sanctioned by California. It is actually an older, longer-standing process than CEQA," Caruso said last month. "And we did it because the Westfield Corporation was very clear in telling us they were going to sue us under CEQA — that’s their culture and that’s what they do as a business, is try to stop competition."

But Eric Munoz, a board member of the Agua Hedionda Lagoon Foundation who worked with the city planning office for seven years, is skeptical. Unlike other board members who support the project because 85 percent of the land is to be preserved as open space, Munoz focused on the 15 percent of the land to be developed commercially.

Munoz said under CEQA, the city, not the developer, would be the lead agency defending the project from lawsuits and that a well-designed project should survive CEQA suits.

"If there were some lawsuits I can’t imagine any that would have knocked the project offtrack if it complied with all the coastal and land use designations that it had to deal with," Munoz said.

Under CEQA, plans are reviewed by many different agencies and interested parties, Munoz said. Under the initiative process, the plan is reviewed only by city staff.

Many supporters cite their trust in Carlsbad city staff to do a good job. Caruso said his proposal was exhaustive.

"We did every single study that would have been required under CEQA," Caruso said. "And we gave it to the city and they did an independent review of all of our studies: 4,000 pages. So anything that would have been done under CEQA was done."

But DeAnn Weimer of the nonprofit group, Citizens for North County, which opposes the project, said while developers have to present detailed plans under CEQA, Caruso’s plan is conceptual. For example it complies with height limits but there are no engineering drawings to be reviewed.

"We don’t have the plans," Weimer recently told KPBS Midday Edition. "We haven’t seen the plans, and the fact we’re being asked to vote on this is questionable — we’re concerned that people are being misled by the Caruso Affiliated operation."

Caruso said he has spent three years and more than $7 million of his own money building community support. He engaged community members to sponsor the original initiative, which passed in July 2015. The Carlsbad City Council then approved the project.

But that wasn’t the final word. Opponents rallied and a citizen-backed referendum (without any financial help from Westfield) overturned that approval and put it on the ballot for a public vote. Westfield has since donated $75,000 to those campaigning against Measure A.

The Carlsbad City Council, which unanimously supports the plan, decided not to wait until the June primary but to spend more than half a million dollars for a Feb. 23 special election.

Caruso said he may not save money by using the initiative process, and it remains to be seen if he will save time. There is no guarantee Westfield will not sue, even if Measure A passes. Although Caruso has said his project is designed for Carlsbad residents, it’s envisioned as a destination location on a scenic lagoon for people around the region and could draw customers from Westfield’s mall on La Jolla Village Drive and beyond.

Other developers with visions for new projects may be watching this month’s election to assess if going directly to the people for a vote rather than going through a CEQA review saves time or money.

If Measure A passes, the California Coastal Commission still has to sign off on the project. If it fails, Caruso said he cannot make another proposal for that location for 12 months.