Editor's note: This is the first in a four-part series. Here are parts two, three and four.

Donald Trump promised to build a wall at the border. In part one of this series Jean Carrero explores the consequences of existing border barriers. What may happen if they expand. She joins the search for one loss migrants body. I am hiking one of the borders deadliest smuggling routes. A documenting the search for a 20-year-old Mexican who vanished while entering the US to the Arizona desert. He just had a baby in Mexico City and wanted to send his family money. His great uncle walks beside me. He reads me a text message with the crucial clue. [Spoken in Spanish] It is from a drug mule. He said it appeared he died of dehydration or heat exhaustion. If we find them, it is bad news for me. If we don't find him, it is bad news either way. We are with men that call themselves Eagles of the desert. They search for dead or dying migrants during their free time. The plumbers, farmers, construction workers. Mostly immigrants who live in San Diego. Everyone is sweating and it's hot out here and were carrying heavy backpacks of water and medical supplies. The men are all ages. The youngest is a teenager and the oldest is in his 70s. His parents brought him to the US when he was two years old. I feel American but at the same time, my roots are from Mexico. I try to help out as much as I can. He is very tall and 10. The earth is unusually few -- Fertile for a desert. Foliage cleanings and their canopies above our heads. Is impossible to keep sight of each other. We repeatedly have to stop and regroup. Rowing Whistles to find each other. Signs of migrants are everywhere. Into water gallons, toss backpacks, dolls, even shredded women's underwear. It is creepy. Snakes, scorpions, cattle skeletons. We have to make it out before sunset before smugglers come out that inhabit this terrain. Hundreds of people die in this desert each year. The deaths started with construction around cities in the late 1990s which pushed migrants on some remote dangerous desert routes. Fatalities since the 90s ranges as high as 10,000 That is more than American soldiers killed in Iraq. It's a staggering toll for a public policy Donald Trump has vowed to expand current Fencing. We are going to build a wall. Trumps wall would funnel migrants into even more dangerous areas. We haven't had a serious policy discussion. The oncologist stairs. -- The uncle just stairs Unfortunately, which is found remains of a human being. We need DNA. The family may have closure soon. KPBS news.

A very disturbing story. As we heard, we're not sure that the body recovered by Eagles in the desert was the person they were looking for. There was an ID belonging to. We have a Gregory Hess whose office is how to identify more bodies of people trying to cross the border than any other jurisdiction in this country. Mr. Hess, thank you for joining us. So tell us, where are you in the process of identifying the body they found in the story? There was a some card from a cellular phone fans with the remains. The phone itself was not found. We were able to pull some numbers from that card that corresponded to Guatemala numbers. Those numbers were given to the Guatemala Council at who called those numbers and they did contact a family that was missing a loved one. Circumstantially they believe the person that they are missing could be the remains that we found. And so now we are doing a comparison of DNA between the remains that we found to the family reference sample DNA for the family members in Guatemala. Even of the body does have an ID on it, that doesn't necessarily mean that you have solved the question. That is correct. People travel with false identifications. It might be their name but a different picture or the picture but the wrong name. It could be an identification they have for another person and they weren't using it really as false identification. And identification is a place to start. It could represent the person that we have to we need to prove it one way or another. This is not an uncommon circumstance for your office. You are frequently confronted with identify the bodies of migrants crossing the border. Tell us how many? We have examined the remains about -- of about 2500 people we believed to be migrants since 2001. We average about 170 per year between 2000 We average about 170 per year between 2003 2015. In 2016, we have received about 142 remains. Why is it your office has the largest number of bodies of migrants crossing the border quick It is a matter of people changing patterns in response to enforcement. When people just to cross into the United States illegally from Mexico back in the 1980s and the early 1990s, they would cross near major population areas. Tijuana and San Diego and things like that. There wasn't a lot of determined there and there was not a lot of Fencing. Border patrol did make it much more difficult to cross in the major population areas with the intent to decrease the number of crossings. But it did not necessarily work out that way. People just moved to last patrolled areas and more remote areas including southern Arizona. Are you concerned about plans to extend the wall? I have no idea. That is an unknown. Talk a bit about how many of the bodies that your office receive are actually able to be identified. We have identified about 65% of the total remains that we have received. About 1500 or 1600 people. We still have 800 and 900 individuals that are unidentified. It doesn't necessarily mean the remains are still here. We can keep them indefinitely. If we have finish with our examination and it doesn't look like we have any good leads on an identity, those people will be interred in the County cemetery. They are not loss. If they are identified some day, we can return those remains to family members. What are the challenges of identifying these bodies? There's not a great system to do that. You are dealing with people that you believe to be foreign nationals. There are multiple different countries. And dealing with consulates and people that may not be in the United States or speak the language, try to find missing person report is for those people, there is no databases that exist in the cover all of these eventualities. Decomposition of remains. There are a lot of different challenges in terms of trying to identify this group of people. Yours is a very hard job but a very important one. Is a rainy thing the families are people can do to make your job easier quick If people are looking for missing loved ones, that will increase the odds that they will be found. There are Facebook sites that help with this. Trying to submit sample DNA to various databases, various humanitarian groups, local governments in the country that they come from that could help on the identification process. Just looking is helpful. Some families haven't either heard from people in a long time where there's simply not looking in that decreases the odds of identifying who they are Thank you for joining us

I scan the earth for human skeletons along one of the deadliest smuggling routes just north of the U.S.-Mexico border. Cattle skulls grin without teeth; a scorpion crawls over twigs; the ribbed skin shed by a snake crackles under my boots.

“The vultures are following us,” says Jose Genis, one of a dozen men hiking beside me. He is squinting at some black figures in the sky. “We may be getting close.”

We are searching for Marco Antonio Garcia, a 20-year-old Mexican who vanished after entering the U.S. illegally through the Arizona desert on July 26. He wanted to earn U.S. dollars to send his wife and newborn. Donald Trump had not yet been elected president, but word of his proposed border wall — “el muro,” in Spanish — had reached Mexico City. Garcia crossed on foot and alone, in a hurry, using a smuggler who guided him by phone.

He was carrying a cell phone, a gallon of water and a Bible. We expect he will be dead.

A self-described drug mule called Garcia’s family from the young man’s phone a few weeks after his crossing, saying he had come across his decomposing body — and phone — in the Tohono O’Odham Indian Nation.

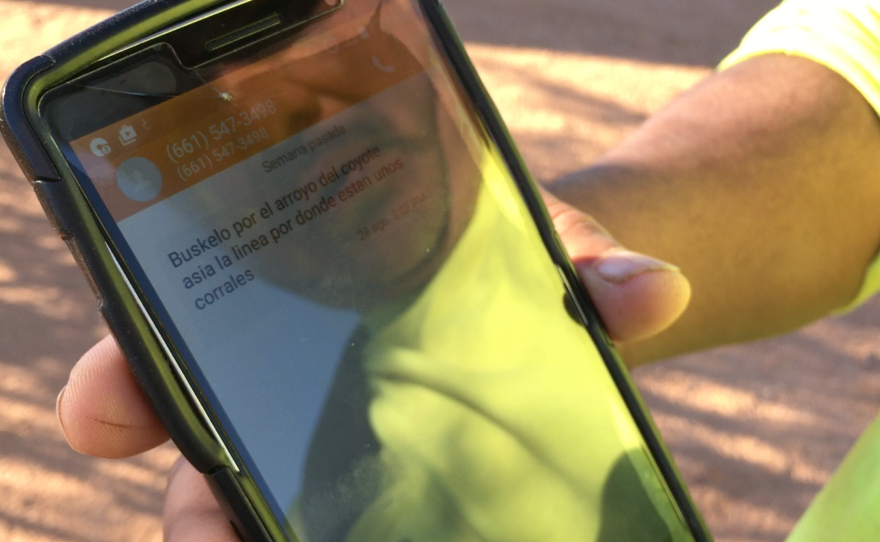

Garcia’s great-uncle, Máximo Garcia — whom I call “Don Máximo,” a customary Mexican title for elders — hikes with us. He shows me a cryptic text message from the drug mule:

Buskelo por el arroyo del coyote asia la linea por donde estan unos corrales

“Look for him in the coyote arroyo near the border by some fencing,” it reads in misspelled Spanish.

It is a crucial clue about Garcia’s whereabouts. Men who call themselves Aguilas del Desierto, or Eagles of the Desert, have volunteered to search for him here, in the Coyote Arroyo. We are spread out in a line that intersects the dry riverbed. The volunteers — mostly immigrants who live in San Diego — have invited me to document the search.

The men are farmers, plumbers, construction workers. On weekends, they risk their lives to rescue dying migrants or locate their remains along the border as far away as Texas. The youngest is a teenager, the oldest in his 70s. Their builds are diverse: lean, muscular, paunchy. Most have brown skin. They speak Spanish. Occasionally, female volunteers join their searches, but this time, I'm the only woman here.

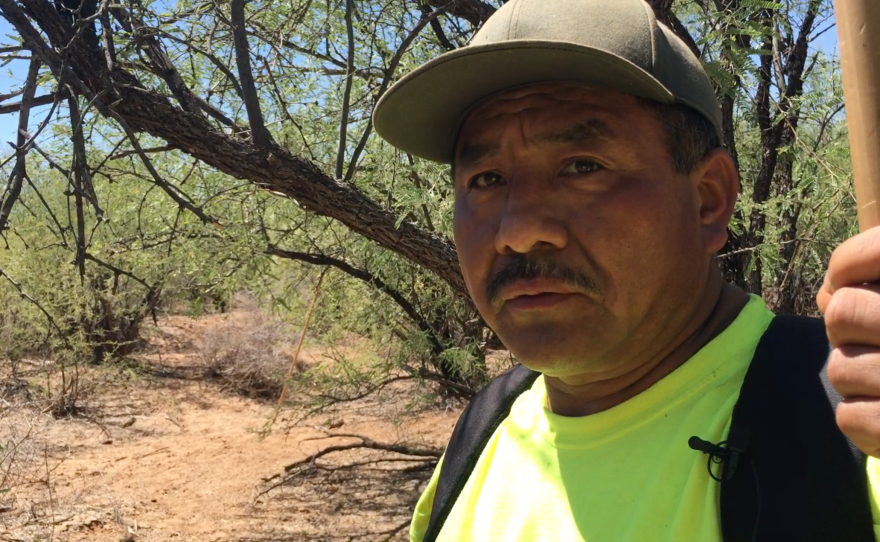

Related: A Brother’s Fatal Journey Inspires Altruism

Genis, sweating beside me in the 100-degree heat, is the vice president of Aguilas. The 31-year-old is a licensed EMT and Navy veteran whose parents brought him to the U.S. when he was two. “I feel American, but at the same time, I have my roots in Mexico, so I try to help out as much as I can,” he says. Genis is tall, with broad shoulders and close-cropped black hair. He's soft-spoken.

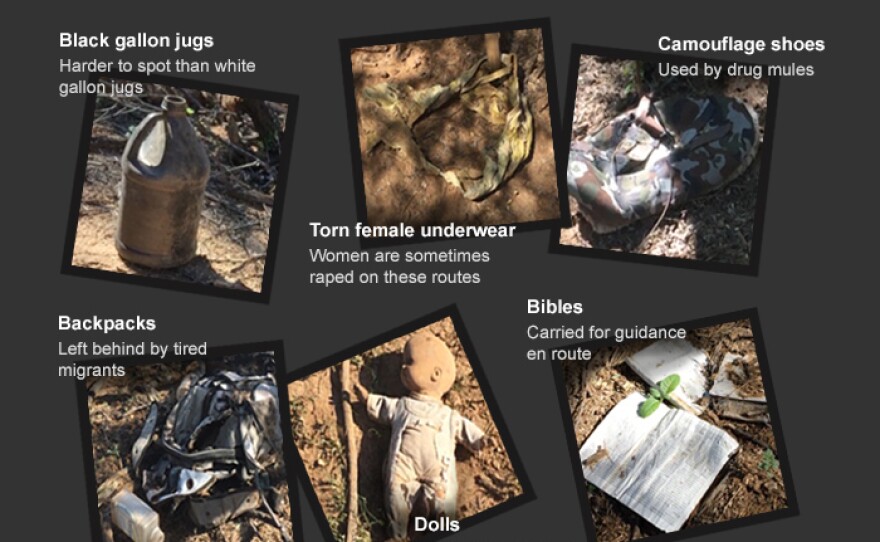

Signs of migrants are everywhere — tossed Red Bull cans, backpacks, dolls, electrolyte packages, Bibles crawling with insects and ripped female undergarments.

“Why are there so many of these?” I ask of the underwear, hoping the answer differs from my guess. Genis says the women who walk through here are sometimes raped.

The most prevalent human items — literally dozens an hour — are black gallon jugs. Genis says human smugglers, known as coyotes, sell these jugs to migrants with what they claim is supernaturally stamina-inducing water. The black gallon jugs are also harder for Border Patrol to spot than regular white gallon jugs.

The second-most common abandoned belongings — scattered all around the labyrinth of cacti and shrub — are camouflage shoes with carpet strips sewn on the bottom to cover tracks. Those belong to the drug mules, Genis explains.

The objects are relentless reminders of the human and environmental dangers we face in the Coyote Arroyo. We walk.

How deaths started after a border fence was built

President-elect Trump has promised to build “an impenetrable, physical, tall, powerful, beautiful” wall at the U.S.-Mexico border. Immigration experts and human rights groups believe the expansion of current barriers, which cover nearly 700 miles of the 2,000-mile border, could lead to an increase in the number of people who die trying to enter the U.S. illegally.

“History shows that when we build more walls, it becomes more dangerous to cross,” said David FitzGerald, co-director of UC San Diego’s Center for Comparative Immigration Studies.

Construction on most of the existing barriers was launched in the 1990s, focusing on urban areas. Officials believed the extreme temperatures of the unfenced areas — miles and miles of austere desert — would deter most people from using those routes; nature would take care of the rest. The latter forecast proved more prescient.

Since construction on the border fence started two decades ago, nearly 7,000 people have died trying to cross the border, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Most died of dehydration, heat exhaustion and other problems related to the harsh environment.

Official figures on deaths include only the bodies that have been found. Countless more lie crumbling into dust, lost beneath tangles of shrub where the dying seek shade.

The actual death toll may be more than 10,000, said Ev Meade, director of the University of San Diego’s Trans-Border Institute.

“That’s more than American soldiers killed in Iraq,” he said. “It’s a staggering toll for a public policy of the United States.”

Although net migration from Mexico is at a 20-year low, border crossing deaths remain at near-record highs. Prior to the fence, annual border crossing deaths totaled a few dozen. Now, they’re at hundreds each year.

The death toll is so high, Meade argued, that Americans have a hard time grasping the magnitude of the situation. In the collective consciousness, the dying are anonymous outsiders. Books like Luis Urrea’s “The Devil’s Highway” and, more recently, the Jonás Cuarón film “Desierto” have brought mainstream attention to the human faces behind the statistics. Still, the topic is largely absent from public discourse.

“We just really haven’t had a serious policy discussion or a public discussion about the humanitarian consequences of the building of the wall,” Meade said.

Refugees are replacing economic migrants, he explained. They’re increasingly desperate, undeterred by barriers or risks. A longer fence would only push migrants into still-more dangerous crossing routes, Meade said.

If Trump managed to overcome geography and seal off the entire land border — against the expectations of engineers — migrants would then turn toward the Gulf of Mexico or the Pacific Ocean, Meade said. Tragedies like those unfolding in the Mediterranean, where thousands have drowned trying to reach Europe, might then occur off our coasts, he said.

“The United States is a huge country with two giant seaboards and lots of international airports. There’s no way to put a fence around all of those things,” Meade said.

He said the only thing that will stop the flow of migrants — and their deaths — is improved conditions in migrants’ countries of origin: Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and other areas with rising drug- and gang-related violence.

“The people who are coming are in much more desperate straits,” Meade said.

He called the border fence a “protective metaphor” and “a comfort to people," which has rerouted migrant traffic onto deadly paths.

Border Patrol spokeswoman Wendi Lee argued the border fence can't be blamed for the deaths. Migrants and their coyotes make the journey at their own peril, and coyotes often lie to migrants about the risks.

In the desert heat, migrants should carry at least a gallon of water per day to survive. But they often walk for days with a single gallon or a mere bottle of water. Coyotes fail to prepare migrants properly. They manipulate them, rob them, abandon them.

“A lot of criminal organizations see the illegal migrants as cargo — they don’t see them as human beings,” Lee said.

She said the border fence has helped reduce crime related to drug and human smuggling.

'Bad news either way'

As we continue our search for Marco Antonio Garcia, I talk to the young man’s great-uncle, Don Máximo.

“If we find him, it’s bad news for me,” says Don Máximo, his face blank of expression. “If we don’t find him — well, it’s bad news either way.”

He clings to the idea that this is all a sick joke, that we will find his nephew subsisting on cacti and rain. Hope fuels a never-ending nightmare when it comes to vanished loved ones. Corpses are crucial for closure. The Aguilas search for bodies at the border to help families move on.

I tell Don Máximo that his sentiments are not strange to me. My 16-year-old cousin, Diego Valenzuela, was kidnapped from Mexico City on Sept. 4, 2015, a year before my grim hike through the Coyote Arroyo. The coincidence of the timing of the search for Garcia — on Sept. 3, 2016 — seems meaningful somehow. My family still speaks of Diego in the present tense, although it’s been a year since we heard from the kidnappers.

“The drug mule said the animals were already eating him,” Don Máximo recalls. The claim is too terrible to be credible — at least without tangible proof. Plus, a Mexican curandero, or shaman, told him Garcia is still alive.

'Physical barriers work'

On the West Coast, the border fence consists of steel columns stretching up from the beach like slanting brown teeth. They are placed close together for several meters into the Pacific Ocean, then stop amid foamy waves.

A short walk inland, the fence becomes steel mesh so tightly woven that only the smallest of fingers can fit through the gaps. Corrugated steel barriers — recycled military aircraft landing mats — rise up for many miles east of that, together with a steel bar fence crowned by barbed wire. In El Centro, the barriers stop, accommodating steep, boulder-studded mountains.

Pre-1990s border fencing between San Diego and Tijuana was relatively permeable, consisting of a hodgepodge of materials: chainlink fence, steep piles of sediment, cement blocks, steel columns and barbed wire strung between wooden posts in the early 20th century to keep Mexican cattle from devouring American crops. The construction was rudimentary, easily traversed or trampled.

Shawn Moran, vice-president of the National Border Patrol Council, said the stronger, taller fencing initiated in the late 1990s has made the border more secure, and made it easier for agents to do their jobs.

“Physical barriers work,” he said. “There’s a reason why we have fences around all of our elementary schools in this country. We don’t want people that shouldn’t be there getting into our schools and possibly harming our children.”

Moran said he supports Trump’s proposed wall. However, he doesn’t think Trump can wall off all 2,000 miles.

Engineers and other experts have argued that sealing off the whole border would be nearly impossible because of difficult geography, which precludes the fencing of floodplains and steep, rocky mountains — the most perilous places to cross.

Even if Trump somehow managed to build through or around topographical obstacles, Moran said, people would find a way through. “If you build a 20-foot wall, they will build a 21-foot ladder and they will try to get in,” he said.

Moran concluded that the fence should be one component of a U.S. immigration strategy that focuses on eliminating incentives for migrants to enter the country illegally.

“Until we have good policies that shut down people hiring illegal aliens in this country, we are not going to be able to shut down that flow,” he said.

'Do not lose sight of each other'

We walk.

The earth along the Coyote Arroyo is unusually fertile for a desert. The vegetation clings to our clothes and forms a canopy above our heads. We carry wooden poles and whack our way through the brush.

Tattered clothes hang from tree branches. The Aguilas conduct surveys of abandoned backpacks; garlic cloves tumble out of one, a toothbrush out of another. Someone shows me a half-empty Pond’s Cream jar.

This is one of the most transited border routes precisely because there is so much vegetation for cover. It makes it easier to hide from Border Patrol. But it also makes it impossible to follow the No. 1 Aguilas rule for safety: “Do not lose sight of each other,” Aguilas founder Ely Ortiz reminds us through radio, repeatedly.

The only person I consistently see is Aguilas vice-president Genis. Don Máximo disappears and reappears on my left.

Suddenly, I find myself alone.

My heart thunders in my chest. I call out Genis’s first name.

“José?”

I stop, listening for a response. Nothing. I can no longer hear the static and beeping of his radio. I’m the only person without one. I take a deep breath and try to calm down.

I’m running on about 30 minutes of sleep. After driving nearly all night from San Diego, the Aguilas stopped in a town called Ajo and slept on the rocky desert floor. I tried to sleep on an abandoned cot inside a nearby rat-inhabited barn. I’m exhausted, scared, hauling a backpack heavy with two gallons of water, a medical kit and other gear. My cell phone has no signal.

“José?” I cry, a little louder.

My mind begins posing uncomfortable questions: What if I can't find the group again? What if I run out of water? What if I encounter a drug mule or a gang of criminals?

Finally, I hear Ortiz calling my name. I follow the sound of his voice until I see his neon yellow shirt, the signature Aguilas color for visibility.

We press on. The prospect of finding bodies in this confusing place seems increasingly unlikely. Genis uses his pole to poke through a tangle of vegetation. Thick Mexican blankets are rolled up beneath. But there is nobody there.

“(The bodies) blend in, especially after the body has been decomposing and dust has kicked up,” Genis says.

We look around and realize we can’t see the other Aguilas. By radio, Genis instructs them to blow their whistles. One by one, shrill sounds weave through the trees. Some are faint. Genis tells them to follow his whistle. We converge, then continue.

We have to make it out before sunset, when smugglers roam this landscape. But we aren’t covering nearly enough ground. The dense foliage — ragged branches and twigs that scrape our faces — keeps slowing and separating us. We repeatedly stop and regroup.

Our clothes are soaked with sweat. The earth is crooked and compartmentalized, dropping off into deep seams we must scramble into and out of. I can’t imagine hiking through here for days.

Genis checks our GPS coordinates on his Garmin device. “We’ve moved one mile if anything, a mile and a quarter,” he informs me. “We’re moving really slow.”

It is past noon. It has taken us nearly four hours to cover that distance. We still have four miles to reach a road where Aguilas founder Ortiz and his partners are waiting for us in vehicles. I do the math; it will be dark before we arrive.

'Your first crossing could be your last'

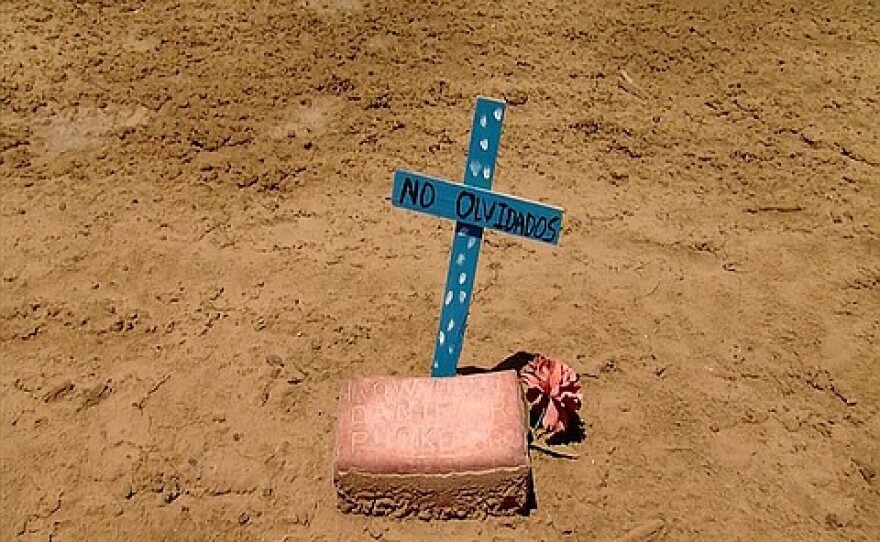

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has a campaign called “No Más Cruces En La Frontera,” or “No More Crosses On The Border,” meant to discourage people in Mexico and Central America from entering the U.S. illegally.

“Your first crossing could be your last,” says one video, showing stacks of bodies at the Pima County Medical Examiner. Another portrays a human smuggler as a literal coyote, predatory, with sharp teeth.

But warning campaigns have largely failed. For many migrants fleeing death threats and violence, it’s already a matter of life and death.

In 1998, in response to skyrocketing migrant deaths, Border Patrol launched a search and rescue unit, known as BORSTAR, which responds to 911 calls at the U.S.-Mexico border with helicopters and trained paramedics. It proved insufficient to address the enormity of the problem.

In 2007, the U.S. built 131 miles of new fencing — more than any year prior. Border crossing deaths reached a record 827, up 70 percent from the year before, according to Mexico’s Foreign Affairs Ministry. The Aguilas formed in 2012 to help Border Patrol’s search and rescue efforts. Other groups, like Border Angels and Los Angeles del Desierto have also joined BORSTAR in addressing the problem. The Colibrí Center for Human Rights recently launched a large-scale DNA collection initiative in the U.S. to help identify the bodies that keep stacking up at the Pima County Medical Examiner.

How To Learn If Unidentified Remains Belong To Your Relative

Call the Colibrí Center For Human Rights at (520) 724-8644 and leave a message with your name, the name of the missing person and your phone number — or submit an electronic report. The organization collects DNA samples from families of missing migrants, and will be focusing on California in 2017. Sampling will occur in Los Angeles in February.

The Aguilas are getting about 18 emergency calls a week, compared with about one a day just a year-and-a-half ago — before Trump announced his wall.

In 2016 alone, the BORSTAR team in the Tucson sector rescued more than 1,330 dying migrants, up from 790 last year and 409 the year before. People are rushing to cross the border before Trump’s term begins. Some are dying on the way.

'We’re kind of hoping it’s him'

Back in the Coyote Arroyo, someone finds something. I scramble up a hill, following Genis and the sound of a whistle.

At the base of a tree, I see a human skull. It lies on its side, mouth agape. Dirt clings to crevices in the bone. A few meters away, legs are clothed in brown pants. The remains are scattered all over the place, as if torn apart by a coyote or some other animal.

Is this Marco Antonio Garcia?

“It’s about 10 meters from the wash,” Genis says. “We’re kind of hoping it’s him, but we don’t know yet.”

Don Máximo just stares. It’s impossible to tell if this is his grand-nephew. In the desert, Genis explains, the heat burns bodies to a crisp within days. Then the animals dig in. But the location fits the description.

The Aguilas note the GPS coordinates of the remains. They read them to Ortiz through radio. They can’t touch the bones; it may be a crime scene. Ortiz shares the location with local police, who will pick up the remains and transfer them to the Pima County Medical Examiner for DNA analyses a few days later.

Ortiz and his partners manage to drive the vehicles closer to us, and three hours later — just before sunset — we make it out of the desert.

Don Máximo thanks the Aguilas for the search. He says they were the only people willing to help him. One by one, the volunteers throw their arms around him or shake his hand. He may have closure soon.

“It’s better this way,” Don Máximo says. “So we can stop fooling ourselves ... and know that he’s with God.”