The federal government announced plans Thursday to lift a moratorium on funding of certain controversial experiments that use human stem cells to create animal embryos that are partly human.

The National Institutes of Health is proposing a new policy to permit scientists to get federal money to make embryos, known as chimeras, under certain carefully monitored conditions.

The NIH imposed a moratorium on funding these experiments in September because they could raise ethical concerns.

One issue is that scientists might inadvertently create animals that have partly human brains, endowing them with some semblance of human consciousness or human thinking abilities. Another is that they could develop into animals with human sperm and eggs and breed, producing human embryos or fetuses inside animals or hybrid creatures.

But scientists have argued that they could take steps to prevent those outcomes and that the embryos provide invaluable tools for medical research.

For example, scientists hope to use the embryos to create animal models of human diseases, which could lead to new ways to prevent and treat illnesses. Researchers also hope to produce sheep, pigs and cows with human hearts, kidneys, livers, pancreases and possibly other organs that could be used for transplants.

To address the ethical concerns, the NIH's new policy imposes several restrictions.

The policy proposes prohibiting the introduction of certain types of human cells into embryos of nonhuman primates, such as monkeys and chimps, at even earlier stages of development than what was currently prohibited.

The extra protections are being added because these animals are so closely related to humans.

But the policy would lift the moratorium on funding experiments involving other species. Because of the ethical concerns, though, at least some of the experiments would go through an extra layer of review by a new, special committee of government officials.

That committee would, for example, consider experiments designed to create animals with human brain cells or human brain tissue. Scientists might want to create them to study neurological conditions such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. But the experiments would undergo intensive scrutiny if there's any chance there might be a "substantial contribution" or "substantial functional modification" to an animal's brain.

In addition, the NIH would even consider experiments that could create animals with human sperm and human eggs since they may be useful for studying human development and infertility. But in that case steps would have to be taken to prevent the animals from breeding.

"I am confident that these proposed changes will enable the NIH research community to move this promising area of science forward in a responsible manner," Carrie Wolinetz, the NIH's associate director for science policy, wrote in a blog post.

"At the end of the day, we want to make sure this research progresses because its very important to our understanding of disease. It's important to our mission to improve human health," she said in an interview with NPR. "But we also want to make sure there's an extra set of eyes on these projects because they do have this ethical set of concerns associated with them."

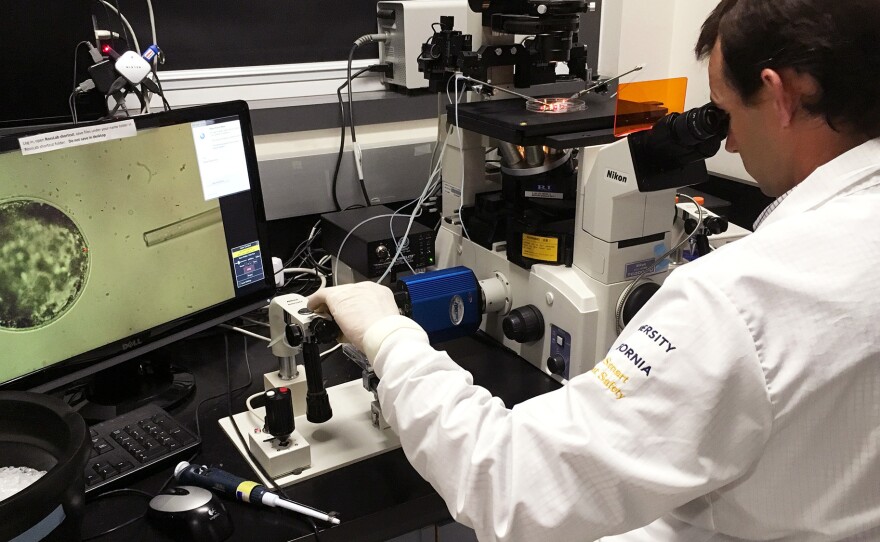

Several scientists said they are thrilled by the new policy. "It's very, very welcome news that NIH will consider funding this type of research," says Pablo Ross, a developmental biologist at the University of California, Davis, trying to grow human organs in farm animals. "We need funding to be able to answer some very important questions."

But critics denounced the decision. "Science fiction writers might have imagined worlds like this — like The Island of Dr. Moreau, Brave New World, Frankenstein," says Stuart Newman, a biologist at New York Medical College. "There have been speculations. But now they're becoming more real. And I think that we just can't say that since it's possible then let's do it."

The public has 30 days to comment on the proposed new policy. NIH could start funding projects as early as the start of 2017.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.